It was mid-afternoon in early February, 2013, in the Laurentian Mountains of Quebec. The temperature was near zero Fahrenheit, further embittered by the driving wind and my passage on cross-country skis. Snow lay three feet deep on the ground, and filled the air with icy slashes. After two-and-a-half hours of that kind of abuse, and that kind of exertion, I was glad to be on the trail’s home stretch.

Like the Action Self-Portraits I take on my motorcycle, this photo was captured in motion. While gliding downhill, my left hand held the camera out to the side and snapped away. At this moment, my eyes were obviously glancing over to check the camera angle, but I like how the expression seems to say, “Are you serious?”

That long, gradual downhill for my photo opportunity came near the end of a fifteen-mile loop (it had been a long, gradual uphill at the beginning). All that time I had been striding over the gentle ups and downs and occasional flats, struggling up the steepest inclines, or nervously careering downhill between the trees. Despite the cold, my inner layers were wet with sweat, and I was tired and pleasantly sore. Like after a three-hour concert, or an all-day motorcycle ride, I was hurting all over — but that was fine. If I drive myself hard, and properly use every muscle, they should all feel it. Just no individual aches in knees, shoulders, elbows, and so on, thank you.

My area of the Southern Laurentians offers an extensive network of cross-country ski trails, but I have always favored one particular loop. I once compared it to a yoga practice, dynamically, for the way it builds gradually in intensity, sustains that pace for a long period of varying terrain and technique, then eases down gently toward rest. It begins with an easy kick-and-glide cruise along an old railway alignment, then turns uphill for about twenty minutes, through alternating degrees of steepness. On a gentle grade, the wax will hold against the snow as I press down before the kick, if conditions are right (and the wax well chosen). Then I continue my rhythmic stride, even sometimes gliding upward a little between kicks, if previous skiers have glazed the surface of any new snow. A few more degrees of rise might require a firmly planted ski with each stride to hold against the backward-slipping gravity. The next level of gradient needs the skis stepped out and edged in at the back, and the steepest of all demand the full splayed-out herringbone, leaving the namesake pattern in the snow.

I always consider that extended climb as my personal “Test Hill.” Every year when I come back to it, it represents a measure of my fitness level. As long as I can do that relentless climb in one go, without pausing, then I figure I’m okay. I do not look forward to the day when I discover I cannot.

Here, through the magic of my personal invention, the SkiCam™ (I lean down over the tips and snap the trail ahead), we see the woods covered with new snow. I was breaking trail through a few inches of powder that had fallen overnight and during the morning. It was mid-afternoon, and nobody had been on that trail before me that day. On a weekday, I sometimes ski that whole two-and-a-half-hour loop without seeing another skier. At most, two or three.

That is part of the reason why if the temperature is below about zero Fahrenheit, I don’t go out alone. In fact, that is around minus eighteen Celsius, the temperature at which long cross-country ski races will be canceled. The cold itself is not uncomfortable, because cross-country skiing generates a good deal of heat. But if anything should go wrong — injury or equipment failure — and you stop generating that heat, you could be in bad trouble pretty quickly. It has to be admitted that I am not the most graceful or coordinated of skiers, and I fall quite often, especially on tricky downhills with narrow curves. Trees are always too close and available to be crashed into, with unyielding hardness. More than once in an out-of-control tumble my skis have clattered into a tree, or I have felt my backpack brush against something hard as I go head over heels. A broken collarbone, or even a twisted ankle, could leave me helpless in unforgiving cold.

Yet of course that very solitude is part of what I like about cross-country skiing, so it can’t be avoided. Just as I face up to the risks of motorcycling while trying to minimize them, I try to be prudent in the winter woods, too. On colder days, or on weekends when more people visit the ski trails, I’ll go out on snowshoes instead. You don’t need a trail with those — you can walk anywhere you want, just head out the door and into the woods, following old logging roads or survey lines. And there’s little danger of a bad fall.

Another rule I maintain in the winter woods (a subcategory of Roadcraft called Trailcraft) is that I won’t cross frozen lakes or ponds alone. More than one neighbor of mine has fallen through a beaver hole, or a place where moving water thins the ice, and clearly that can also mean serious trouble, especially if you are alone.

And that kind of cold bites fast. On that same bitter, blizzardy February afternoon I got back to my snow-covered car at the trailhead. That is always a welcome moment of combined weariness and relief, now free of urgency or the need of will to drive me onward. I took off my gloves to fiddle with my camera, and looked through some of the Action Self-Portraits I had attempted that day, then took a few of the car (Audi S4 wagon — ideal winter machine) half-buried in the driving snow.

My hands had been warm coming out of the gloves, but they were wet with sweat, and before I knew it — not more than two minutes — my fingers were suddenly numb. I tried putting the gloves back on, but they were wet inside, and icy cold already. Reaching into my backpack for the car keys, I couldn’t feel them. I had to look in and find the ring of keys, then claw them out with lifeless fingers. Even to hold the key fob and thumb the button to unlock the car was a struggle. Opening the rear hatch and loading the snow-covered skis and poles inside chilled my fingers even more. The numbness was now tinged with pain, so that I dreaded curving my fingers under the cold door handle to raise it. Behind the wheel, it took both frozen hands to clutch the key between them and guide it to the ignition, then turn it to start the engine. I was more than usually glad to hear the V8 rumble to life and settle into a steady throb. One curved claw pulled the shifter back to neutral, and the handbrake upward. I rubbed my hands, and waited for the car to produce heat.

After a long bout of outdoor exercise, it is a traditional ritual for certain louche and contrarian Canadians (okay, me) to light up a smoke — but at that moment, I couldn’t manage that to “save my life!” (Ha ha.) With thumbs paralyzed and nerveless, there was no way I could operate my LRL (little red lighter). I could push in the car’s lighter, but my dead fingers could not grasp the knob to pull it out. I had to laugh a little at that predicament, and at myself. Safe in my car and headed home, I was not in any danger, but that sudden helplessness was still a little scary.

It reminded me of Jack London’s classic story, “To Build a Fire.” Set in the Klondike Gold Rush in the Yukon in the late 1890s, a chechaquo, newcomer, sets out in the dark midwinter to hike to his remote camp, accompanied only by a “wolf-dog.” The temperature falls to a scarcely imaginable seventy-five degrees below zero — Alaska and the Yukon have both reported eighty below, while the coldest temperature ever recorded was in Antarctica, at one hundred twenty-eight degrees below zero Fahrenheit. (We wouldn’t go out skiing alone in that!)

London illustrates the severity with a telling detail — the man’s spit crackles and freezes before it reaches the ground. His destiny combines bad judgment with bad luck, as tragedy so often does, when he falls through the ice over a hidden spring. He needs to start a fire — fast, while his fingers can still manipulate the matches. The conditions are extreme, man and nature at its most elemental, and so is the man’s fate, vividly described in Jack London’s muscular prose. (Friend Craiggie shared a link to a pretty good filmed version of the story by the BBC from 1969, narrated by Orson Welles.)

In a brief but significant tangent, there is one tiny detail — one word — in “To Build a Fire” (published 1908) that damns it to present-day readers. This sentence appears in an early descriptive passage:

“He held on through the level stretch of woods for several miles, crossed a wide flat of niggerheads, and dropped down a bank to the frozen bed of a small stream.”

You see the problem. It seems a shame that one word might cause a classic masterpiece to be put aside in school curricula. Perhaps another story, less likely to delight a young boy but less apt to offend his parents, would be selected instead. The tale is set in the late nineteenth century, and the word commonly described tussocks of Alaskan sedge grasses — the meaning isn’t racially insensitive, just the consonants. It clearly will not sit well with people nowadays, yet the prospect of censoring the literature of the past, or “bowdlerizing” such words with acceptable euphemisms is problematic, too. That example could be changed to “crossed a wide flat of sedge tussocks” without any loss — and maybe publishers should take it upon themselves to do that. But it would be a big, controversial task.

Among many other writers of the period, Kipling, Twain, Conrad, and Hemingway used the word “comfortably,” and Harper Lee and Ian Fleming even later. Many black writers employed it in “realistic” fashion, which gets a pass — while these days television networks censor even its deliberately absurd use in the classic Mel Brooks comedy Blazing Saddles (co-written with Richard Pryor). I would like to think the future will bring a racial calmness, when words won’t carry forward such prickly burrs from the past.

Anyway . . . Jack London had been on my mind in other ways around that time. I was thinking about his brave credo:

I would rather be ashes than dust.

I would rather that my spark should burn out in a brilliant blaze,

Than that it should be stifled by dry-rot.

I would rather be a superb meteor, every atom of me in magnificent glow,

Than a sleepy and permanent planet.

The proper function of man is to LIVE.

I shall not waste my days trying to prolong them.

I shall use my time.

Jack London (1876-1916)

That is an inspiring vision, all right, and I especially resonate with the thought, “I shall not waste my days trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.”

However, in Jack London’s case, the dates tell the ironic tale. He did not waste his days in prolonging them, it’s true, but the way he lived probably shortened his time. He was addicted to opium and alcohol, and had multiple health problems — some stemming from his hardships in the Klondike, others perhaps from a quirky diet favoring oddities like nearly-raw duck. He was only forty when he died at his Northern California estate, Beauty Ranch, of kidney failure and a suspected accidental morphine overdose. During my Ghost Rider travels in the late ’90s, I visited Beauty Ranch and walked around the ruins of Wolf House, the home he had been building with his wife, Charmian. It burned down just before his death, symbolizing a dream future that he did not live to inhabit. Nearby, a simple boulder marks his grave.

We may contrast Jack London’s credo with one espoused by Ernest Hemingway, who quoted a motto from a statue of one of Napoleon’s generals, “Il faut d’abord durer” — “First one must last.” Or, the shorter version I prefer, “At first, to last.” (That was one inspiration for the Rush song, “Marathon.”)

For myself, I figure I have already “lasted.” As I begin my seventh decade, one frequent realization is the number of people I have outlasted — not only did Jack London die so young, but Ernest Hemingway was just sixty-one when he ended his torments with a shotgun. And how many musicians — how many drummers? Why, it’s the stuff of punchlines. (See This is Spin̈al Tap, Good Night Keith Moon, etc.)

Such thoughts always give me pause — but not in the conventional way. The notion doesn’t make me fear time or aging. To the contrary, I feel like I’ve already won. The rest is all bonus . . .

Photo by Charles Voisin

One Sunday afternoon I was joined on snowshoes by my neighbor Charles (silent “s”), who had been my partner on the “Quest for the Phantom Tower” a few years back. From my door we headed into the woods, following paths we knew well, commenting on the number of trees that had been snapped off by a recent heavy snowfall. Feeling secure with a companion, we traversed frozen lakes and ponds, and passed a few nests left by the summer residents, great blue herons. All the while we discussed the animal tracks we encountered — the stories in the snow. Deer, fox, hare, weasel (ermine, in its white winter coat), grouse, and squirrels. We were especially delighted to see where a moose had been “nesting” in the shelter of some evergreens. Moose are rare in our neighborhood, and still hunted every year, so we are always glad to learn they are still around.

Even from indoors, I had been watching the stories in the snow every day. My birdfeeder, Bubba’s Seeds ’n’ Suet, was busy most of the time, with chickadees, common redpolls, red-breasted nuthatches, and hairy woodpeckers. Below it, tracks had been left by squirrels, rummaging in the snow under the feeder for seeds, or bounding across the white surface from one tree to another.

Pretty well every day I saw a line of prints, straight and purposeful, left by a fox. No matter how often I looked out, even during the night, I never saw the animal itself. Charles told me he saw it all the time, but my single sighting had been the winter before, and that was only for a few seconds, as the reddish body and long tail darted across my yard.

So I was pleasantly surprised one morning to look out and see a fox poking around the feeder, sticking its nose into the snow here and there — probably sniffing for mice. Slowly I backed away from the window and picked up my camera, amazed to have time to snap a dozen shots of it, before it stepped lightly across the snow back to its den in the hill by the road.

A few days later, I looked out the window at another story in the snow, starring my neighborhood fox. (I knew she was a female, having seen her squatting in the snow to . . . micturate. Or as I put it less delicately but more poetically in letters to friends, “I know she’s a she/ ’Cause I saw her pee!”) A line of her tracks led away from the house, at the bottom left, then suddenly stopped, turned left in three swift bounds leaving deep depressions in the snow, then trotted away in a straight line over its surface again. A mousie for brunch, I guess.

I once described the perfect life as a working vacation that never ends. Well, in those terms, at least I had a perfect two weeks. Waking early, with the first hint of light, I looked up through wide-open curtains to greet the day. Sometimes a ballet of snowflakes filled the air, which always makes me happy; other mornings were crystalline, icy hard and frigid-looking. Several nights the temperature plunged to minus thirty Celsius, which is pretty darn cold. The chill emanated from the windows by my bed, like icy fingers creeping through the double glazing. No matter how good your house’s heating, insulation, and window and door seals are, that kind of cold seeps through and gives an edge to the air. An electric edge, even, when you touch something and the super-dry air sparks with static electricity.

Looking out on a severely cold morning, under a sky that seems infinitely blue, the bare trees sway stiffly, like rigid skeletons. The natural suppleness of their trunks, branches, and twigs is paralyzed by frost, and they move in unison like a single frozen sculpture. Seeing those trees, and feeling the chill on my nose, is fine to experience from a warm bed — but there is a day to begin. With a surge of will, I roll out and dash into the main room (sensibly combining kitchen, dining area, and sitting room), quickly sparking up the fireplace with paper and kindling. Then I crawl back under the covers for a while, maybe read a few pages, until the fire starts to spread its spiritual warmth through the house.

Get dressed, make the coffee, squeeze the juice, then settle at the counter to look over the previous day’s writing, and start adding to it. After a year of neglecting Bubba’s Book Club, I had collected a list of twenty-one titles that I wanted to write about. I had thought I would choose a few that most inspired me, but when I noticed they were nearly all novels, all but one from the previous decade, and all by living writers, I recognized a theme. I can never resist a theme — whether it’s Action Self-Portraits, Ghost Rider photographs, or national park passport stamps. I had to try to write about all of those books.

It was hard work, but rewarding in sometimes unexpected ways. It has occurred to me that writing book reviews can be like writing letters — trying to put impressions and reactions into words, you sometimes discover things you didn’t know you knew. I like to paraphrase something E. M. Forster said, “How do I know what I think until I see what I write?”

So I spent my mornings adding pieces to that massive, brain-straining mosaic of words. (See Bubba’s Book Club Issue 17). Somewhere along the way I would fix some breakfast — soft-boiled eggs with raisin toast, Shreddies cereal (a Canada-only favorite), or blueberry waffles with Quebec maple syrup — then carry on writing until just before noon. Then I would close the laptop and change into my long underwear, fleecy top, windbreaker, boots, and gaiters, and gather up the scarf, balaclava, and gloves that had been drying from the previous day’s outing.

Every few days my property manager and majordomo Keith would drive out from town to bring me some groceries, then stay around to tidy up and load in more firewood (I burn a lot). In two weeks I never drove farther from home than a few miles to the ski trail, out only once at night to visit neighbors Paul and Judy for a welcome dinner-not-cooked-by-me. I visited the nearest village just one time, to get gas for the car. I liked being a recluse like that — it suited me. At least for a while.

I stow a sandwich and some drinks and snacks in my old backpack, and drive to the trailhead. Cold days with fresh snow are easy to wax for — Special Green most of the time, crayoned along each ski’s “wax pocket,” under the binding, where you press down for grip to kick forward. Then lay the skis flat on the snow, step into the bindings, strap the poles around each wrist, and — shove off.

In “The Best February Ever,” back in 2008 (can it really be five years?), I described that state of mind: “Many times I have noticed that as soon as I plant my skis in those parallel tracks in the snow and push off, it seems as though my mind is suddenly transported.”

With all of those books to think about, I had no lack of raw material. And even better, none of that was pressing — yet it was rich with possible insights, connections, and revelations. Another quality I observed in that story: “On the ski trails, while I’m kicking and gliding across the snowy landscape, thoughts parade through my mind in a somehow stately fashion, without urgency.”

So it remains for me, and my thoughts ranged from postmodernism to what I might eat for dinner (simple comfort-food basics in my solitary retreat — pasta with shrimp sauce, ribeye steak fried in butter and garlic with boiled potatoes and broccoli, pork chops with apple sauce and jasmine rice). As always, my mind gathered what I saw and felt and played the game of trying to put it into words, into sentences, that might be shared with others.

Home by late afternoon for a hot shower and maybe a nap, I would stoke up the fire again and pour myself a large Macallan on ice. That was one of the day’s rewards — but only one of a series of prizes, on a day like that had been. The day itself was an unforgettable treasure. My body felt heavy as I sank into the armchair, feet up on the ottoman, and relaxed into the satisfying bone-weariness, and the mental emptiness from having exercised my brain, too. Now I would soothe my body with ease and whisky, and reading over the morning’s work, red pen in hand, was a reward for the mind. (As was the whisky.)

I was careful to glance over at the windows regularly, not wanting to miss any of the phases of changing light as evening came on. Sometimes I would stand up and walk around from one view to another, maybe catching a brief, evanescent light effect that lasted less than a minute. The line of treetops far across the white lake turned pinky gold in the last rays of the lowering sun. Before the snowy ground faded into blue shadows, it seemed to pause and radiate its whiteness even stronger than in sunshine — briefly holding onto the light, like, say, the walls of Grand Canyon. But this radiance was soft and gently rounded, like cake frosting, while the trees were dusted with light snow. Through the hemlocks to the west, an orange spark glinted and faded, and above, the sky turned white, then pale blue, fading to pink around the rim.

So that was one latitude of my experience with winter solitude, winter sports, and winter’s blessings — up around forty-five degrees North. However, most of my winter season was spent a little more than ten degrees of latitude closer to the Equator, in Southern California.

At the risk of understatement, winter is different there.

Still, it should be remembered that Westside Los Angeles, at thirty-four degrees North, sits only halfway between Canada and the true Tropics, north of the Tropic of Cancer by another ten degrees plus. So Southern California is not tropical, but has a temperate, “Mediterranean” climate. It is sometimes moderated by the Pacific Ocean, other times chilled by Alaskan currents and weather patterns. The seasons retain a subtle rhythm, and in winter, it can get chilly. Driving or bicycling on the wider east-west boulevards on clear days, the snow-capped San Gabriels make a postcard backdrop behind the columns of towering fan palms. Once every decade or so, snow will dust the Santa Monica Mountains above Malibu.

One January morning I rode my motorcycle over the Santa Monicas to the other side of the San Fernando Valley, to go for a hike with Greg Russell (Master of All Things Creative — graphic arts, music, animation, this website, visuals for the band’s live show). We call our hybrid sport “motohiking,” where you ride some twisty canyon roads to get to a hiking trailhead. Those mountains feature a wonderful network of “sporting” roads, just minutes from my home.

While riding over Malibu Canyon at about eight o’clock that morning, my bike’s thermometer showed thirty-six degrees Fahrenheit. (Good thing I’m Canadian, and know how to dress for that. That’s why my American motorcycle-touring partner Michael, with his characteristic cultural insensitivity, calls us “Icechuckers.”) Twice that January Greg and I started our hikes at forty-one degrees — but Greg grew up on Long Island, New York, so he knows from cold. And when you’re marching in the Santa Monica Mountains, with plenty of uphill work under a radiant sun, cool weather is a benefit rather than a hardship.

That is not the case on a motorcycle, or in an open car. In my early twenties, my first car was a purple MGB roadster, and growing up Canadian also taught me how to drive with the top down in chilly weather. You wear a hooded jacket for your ears and neck, leather gloves for your hands — and turn up the heater and defroster full blast!

The right music can heat things up, too. On this afternoon drive up the Pacific Coast Highway, temperature in the forties, I was blasting not only the heater, but a gorgeous-sounding album (Eyes Open, 1992) by the great Senegalese artist, Youssou N’Dour. (One singer not noted for humility, Bono, once described Youssou N’Dour as “the best singer in the world.”) His music’s blend of African, Western, and Latin (exactly between African and Western, it occurs to me for the first time) influences cannot help but warm the day.

Around that time, music was also on my mind, and working on my body — or at least, my body was working on music. Getting ready for it, that is — it would soon be touring time again. As described in a story last year, “Gearing Up for the Road” (see “Articles”), even before I became very, very old, I was fairly disciplined about tour preparations. The band had only finished Part One of the Clockwork Angels tour in early December, so I hadn’t really got out of shape yet. For me, the performance edge starts to dull after about three weeks, but my general fitness had stayed strong — hiking in January, cross-country skiing and snowshoeing in early February, and later that month, back to the gym and the pool three times a week.

Hiking in the mountains is always a worthy alternative to a workout session — great exercise in a much more attractive environment — and I was happy to play hooky from the Y to join Greg for some good marches in beautiful settings. Winter is by far the best season for hiking in our area, when the landscape is greener from the rains, and the temperatures are cooler. Not as cool as the above extremes, generally, but better than summer days, which can often be triple digits. The same goes for motorcycling and top-down driving. Winter is also the time of year when I am most likely to be at home, as the band does not tour in snowy climes. (Because, um . . . motorcycling?)

Every winter in recent years Greg and I have been getting together now and again to enjoy the scenic and challenging trails we’ve hiked before, and to explore new ones.

Photo by Greg Russell

This seemingly wild and remote scene is actually a suburban park in the San Fernando Valley, near an area known as Ahmanson Ranch (now the Upper Las Virgenes Open Space Preserve). Its area of 3,000 acres may not sound like all that much of an “open space,” but the landscape is intricately folded to create a maze of narrow valleys and ridges. They are upholstered in a similar variety of grasslands and California live-oaks, so one area can look much like another, and the trails are not well marked.

Greg and I hope to volunteer to help correct that someday, as others have done in the older parks and usually well-posted trails in the Santa Monica Mountains. On our first visit to Las Virgenes, we had maps and a planned route, even Greg’s handheld device with GPS, but there were too many game trails and old ranch roads branching off everywhere. We kept our sense of direction, and bushwhacked a little to get to the trail we wanted, but maybe we were lucky. Just a few years ago a father and son got lost in that seemingly enclosed and limited space — got off the trail and couldn’t find it again. With dark coming on, one of them became dangerously hypothermic, and they had to call for rescue. Even a small slice of “the wild” has to be taken seriously.

This preserve is a modern miracle. Surrounded by endless miles of tract houses on three sides, with the Simi Hills behind, the park was set aside as recently as 2003. Under sustained public pressure, a bank abandoned its plan to build 3,000 homes on the site, and sold the land to the state as a park.

Outsiders might not think of “hiking” and “Los Angeles” in the same breath, but a map of the city shows a crazy quilt (apt metaphor!) of built-up areas and many green patches — natural sanctuaries. Hikers, dog walkers, nature lovers, mountain bikers, and equestrians appreciate them, and use them. Wildlife is plentiful, too — mule deer, coyotes, bobcats, raptors, roadrunners, rattlesnakes, even a few mountain lions. The remnant big cats that roam the Santa Monica Mountains are all numbered and radio-collared, and sadly do not amount to a ”viable population”, but they still occasionally make the local news by somehow managing to cross a ten-lane freeway into a different park. It is not the kind of Tinseltown story that titillates the tabloids, or makes the entertainment news, but we should remember how hard people fought — regular people and elected representatives, even celebrities — for some of these preserves.

Photo by Matt Scannell Esq.

When I am out on the trails in Quebec, if I encounter one of the ski patrol people (not that often, but still), or start out from their parking area and booth in the village, I like to buy the trailpass. For generations volunteers and low-paid seasonal workers have maintained those trails, marked them clearly, secured permission to cross private lands, and these days even groom the trails with snowmobile-drawn tracksetting machines. (We used to break our own trails, and that was fine — but now is better.)

Down in my other “winter latitude,” Temescal Gateway Park, just off Sunset Boulevard, is a narrow canyon of mixed woodland and scrub around an intermittent creek. At the top is a waterfall, varying from a trickle in dry weather to a torrent after winter rains. The name Temescal comes from a word in Nahuatl — the language of the Aztecs — meaning “sweatlodge,” brought north by the Spaniards. Perhaps native dwellers in this canyon built similar structures — but that is among the many things we will never know about those people. Even what they called themselves is lost to history — they are known only as the Gabrieleños, after the San Gabriel Mission that “civilized” them so fast they didn’t even know who they were anymore.

From the Temescal parking area, trails loop upstream through sycamores and mudstone formations to high chaparral ridges looking out over the glittering blue Pacific. In the distance lay the silhouettes of Santa Catalina and some of the Channel Islands. The park charges a modest parking fee, to contribute to the maintenance of the trails (they take a beating in winter’s monsoon rains). However, on weekends I see many people parking their cars up and down nearby streets, then hiking on into the park — as if they are getting away with something. And I guess they are — but not what they think.

Photo by Greg Russell

Before our second visit to the Las Virgenes Preserve, Greg sent me a note, “Do you want to start in the same spot or try the Cheeseboro entrance? I just went to Cheeseboro for the first time on the bike and it was beautiful. Happy to start from there, or at Vanowen and Valley Circle where I can show you some badass caves.”

I wrote back, “You had me at badass caves.”

In the earlier photo titled “Before the Cave,” we are climbing from little El Escorpión Park (named after a nearby mountain, now called Castle Peak, and a Spanish-era rancho) toward the gash in the rock at center. You enter the cave there and climb high, and steep, through water-sculpted passageways to the top, below the notch in the central ridge. It was a hand-over-hand, scrabble-for-toeholds kind of climb — mild considered as rock climbing, but fairly extreme for hiking.

When we emerged from the chimney and clambered over the boulders to the top of that ridge, we looked down over a stunning view. The hills and valleys were draped in velvety green, dotted with darker live-oak trees, and traced with brown trails and fire roads. Only in the far distance could I see a flat and unnaturally geometric arrangement of streets and houses.

For me, the view is the keystone feature to every favorite hiking trail — it should lead upward to some high place with a spectacular vista. Ideally, that point should come about midway through the hike, to make a lunch stop. Like the following setting, where Greg and I have often hiked — the Eagle Rock loop in Topanga State Park. I took another friend, Matt Scannell, around that trail for the first time, and as we packed up after lunch to head down, Matt said, “This restaurant has a great view.”

Add all the clichés about food tasting great outdoors, and after exertion — because it’s true. Much depends upon lunch.

Photo by Matt Scannell, Esq.

One of the pleasures of hiking with a friend is talking. That is also true of snowshoeing, for the same reason — because you can walk side by side, or close behind, and carry on a conversation as you go. I have done a great deal of hiking and snowshoeing alone, and solitude is fine on a motorcycle, or while cross-country skiing — where you wouldn’t really be able to talk to a companion anyway. Just as snowshoeing with Charles is a friendly encounter between neighbors and nature lovers, hiking with my friends encourages companionship and talk, and the time and distance pass easily.

While Greg and I hike, we share thoughts about our children, our friends, our work, music, motorcycling, stories from our pasts, and bad jokes. We tend to laugh a lot. In his early forties, Greg is a generation younger than me, and one time he told me he gets tired of hanging out with guys who complain about their wives all the time. We don’t do that. It seems disloyal, disrespectful, and . . . almost always boring for anyone else to have to listen to.

Another reward of time spent at home is — well, time spent at home. When you travel a lot, for work and for Icechucker sports, then participating in the smallest details of everyday life can seem like luxury. Being a good husband or father is not attainable without the basic element of one’s presence, but I try to make up for it when I am home — making Carrie less of an abandoned wife and single parent, and three-year-old Olivia less of a fatherless child.

Getting up early with Olivia, making her breakfast, shopping and cooking, and important tasks like drawing and coloring — it all signifies. When Olivia was a baby and I went away on tour, she didn’t miss me so much — there were others to take care of her needs. These days, as her awareness grows along with our closeness, Daddy’s absences can be upsetting for her.

When I was away on tour in 2012, Olivia and I communicated best by drawing pictures together over computer video link. Whether on a motel notepad, or the back of a postcard, Olivia “directed” me in creating immensely complicated sketches. I showed them to her as I went, and she suggested ever more intricate details.

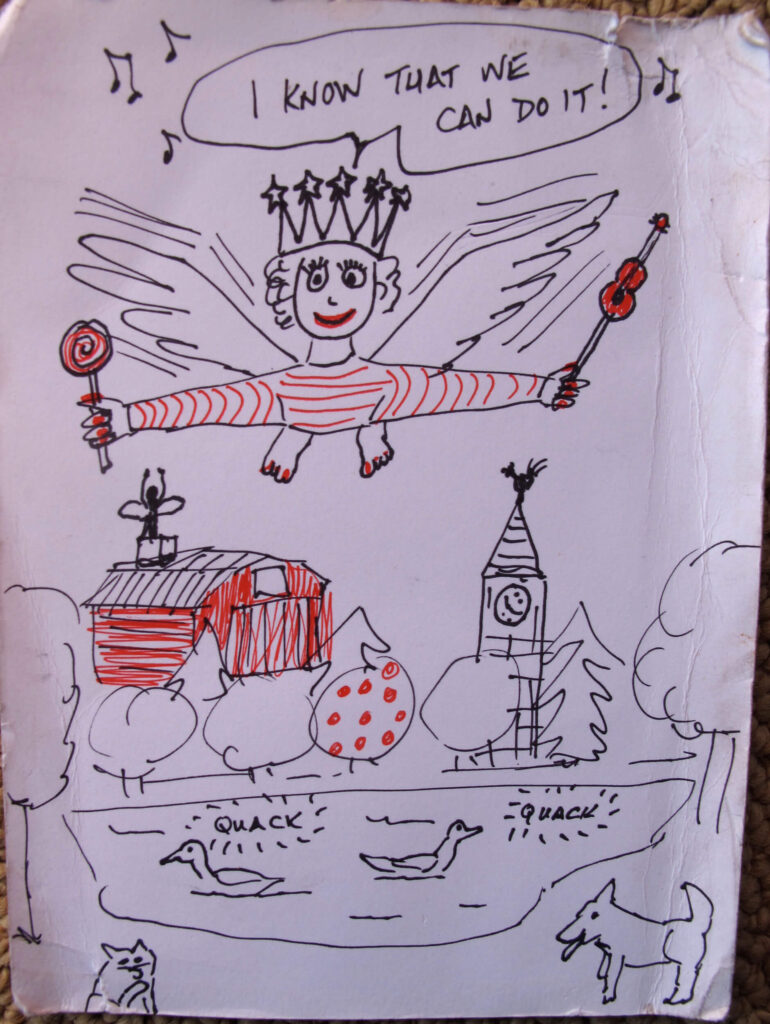

This one, for example, was drawn on the back of a postcard from the Ritz-Carlton in Toronto, while Olivia guided my black and red marker pens.

I asked Olivia, “What should I draw?”

“You should draw Olivia — she should be flying.”

“What should she be wearing?”

“Red and white striped pajamas. She should have bare feet.”

“What kind of wings should she have?”

“She should have feather wings.”

Then the ideas came more quickly, “She should have a crown, with stars on it.”

“She should be holding a wand.”

I asked her, “What shape should the wand be?”

“It should be shaped like a guitar.”

(Brilliant ideas she comes up with, all the time.)

“She should be holding a spiral lollipop.” (A particularly symbolic object to Olivia, especially after our visit to F.A.O. Schwartz in Manhattan, where their candy department’s huge display of spiral lollipops amazed her.)

“She should be singing.” When I asked what song, Olivia went into this verse from “Dora the Explorer.”

She told me the tower should have a “normal weathervane” (like in The Old Red Barn), while the barn should have a weathervane “shaped like a fairy.”

(Of course.)

And the ducks, “They should be quacking loud.” (She knows we show things that are loud or bright with little lines radiating out from them.)

“There should be a dog — he should be panting.”

“There should be a cat — licking its paw.”

And so on. I just drew what she said . . .

Another project I have undertaken in this winter latitude is assembling a book called “Art With Olivia.” I gathered all of the little sketches I did for her while I was away, and photographs of many of our large-scale works, done at home on her work table — sometimes over two or three days.

I wrote down what I could remember of the “narrative” behind all of that art, and also included a number of the songs we have composed together. That kind of magic often happens while I push Olivia on the swings. Something about the rhythm of swinging brings out the music in us.

Sometimes we are in the back yard, or at one of the local parks, or where people in the neighborhood have hung swings under the big trees along the street in front of their homes. (Very neighborly, that.)

Olivia is a cowgirl, a mermaid (here wearing a T-shirt from Uncle Craiggie that reads, “I’m Really a Mermaid”), a firefighter, a ballerina, a gymnast, and a fantastic art director and songwriter. Some of our songs are extended ballads, built up verse by verse over many swinging sessions, while others are riffs on standards like “Swinging on a Star.”

Because I do not share such experiences every day, they are all the more precious to me. And so are the memories. One time when Greg and I were hiking, we were discussing Indian — Native American — names, and I decided mine would be, “Brave Manywinters.”

I am pleased and proud to add this winter to my ever-growing collection, and I hope to gather a few more yet. Especially for Olivia’s sake. However, not my decision to make, of course. So, like Jack London, “I shall not waste my days trying to prolong them. I shall use my time.”

Perhaps not wisely, but as well as I can — in every season, at every latitude.

by a fan on our Clockwork Angels tour.

Now that's cool.

And warm!