It was a summer Saturday in 1970, and I was playing with the band J. R. Flood in St. Catharines, Ontario. We were set up on the back of a flatbed trailer on James Street, closed to traffic for a Saturday “whoopee.” The idea was for us to entertain the youngsters, confound the adults, and share a $250 fee. Pictured are the late organist Bob Morrison and guitarist Paul Dickinson, and we had bass guitarist Wally Tomczuk and singer Gary Luciani. I was seventeen.

All of those guys were pivotal in my musical development—each in his own way. Bob as a consummate, consumed artist; Paul as an exacting, disciplined, yet passionate musician; Wally as a solidly-grounded person whose equally grounded bass playing kept my flights of fancy rooted in “real time;” and Gary as a lead singer, lyricist, and front man who somehow managed to leave ego out of that job description (and who was the first singer to sing my lyrics).

An old photograph is a powerful time machine. Personally, I haven’t kept any scrapbooks or albums for a long time, but lately a lot of my “pre-modern”—even ancient—history has been emerging from heaven-knows-where, sent to me in e-mails and envelopes from various sources.

Now I wonder with some trepidation, “What will they find a photograph of next?” It seems every possible file of ancient yearbook photos has been finely combed, and many dusty boxes of black-and-white prints by amateur photographers have been found in basements and attics.

Back in the late sixties and early seventies, hardly anyone I knew had a decent camera, and considering the cost of film and developing, the few that existed were more sparingly used. Nowadays every handheld device can take a picture.

(That was one of my suggestions for the title of our tour this summer: “RUSH: Handheld Devices.” But eventually, for all good reasons, “Time Machine” won out.)

In any case, it is remarkable that such images as these were taken, saved, put away and lost for several decades, and found again. Then that they made their way to me—forty years later and 3,000 miles away.

Looking at this particular image can send me off in so many directions. My eyes go straight to those drums, the first good set I ever owned: gray ripple Rogers. Not long after that photo was taken, I stripped them down to the bare shells in my bedroom, painstakingly disassembling all of the hardware, and covered the gray ripple wrap with “chrome” wallpaper, to emulate Keith Moon’s Tommy kit. Only two years or so previously, I had added the second eighteen-inch bass drum (little cannons like that represented a certain “style” then—a hangover from mod, I guess), and another twelve-inch tom. In addition, I had a fourteen-inch floor tom, a chrome “Powertone” snare (a model below the Dynasonic I coveted), thirteen-inch high-hats on a stand with a homemade height-extender, and two Zildjian cymbals, a twenty-inch and an eighteen.

That day, I remember my twenty-incher was cracked, and I couldn’t afford a new one. A friend of the band’s, Greg, was a local drummer who had a somewhat less violent playing style than my own, but he lent me his twenty-inch Zildjian for that show. I still consider that a brave and generous act. (I didn’t break it.)

My pantlegs are rolled up like a clown to prevent the bass-drum-pedal beaters from fouling in my flares (I use a bicycle clip these days), and the drumsticks are played backwards, “butt-end,” because I couldn’t afford to replace broken ones, so turned them around and used the other end. I’m sitting on a little square pillow (“liberated” from my mom) atop an upturned metal barrel (in which my dad’s farm equipment dealership sold calcium carbide for bird-scarers—sigh, so much needs to be explained when you’re telling about a time machine: those bird-scaring devices looked like a long megaphone atop a box, and they made a loud explosive noise from time to time, to scare birds out of orchards and vineyards). That steel barrel also served as a hardware case, because after the gig I could fill it with the stands and hardware.

A drumset is a time machine, literally speaking—a machine for keeping time—though a drummer has to be the clockwork device to subdivide rhythm—to bring the time.

In those days, I was not that drummer.

In the opening photo, guitarist Paul is giving me what I can only describe as an “incredulous” look (he was both disciplined and disciplinarian, and I learned a lot from Paul in those days, like how to watch his tapping foot—a time machine if ever there was one—to keep the tempo). At that moment, I was probably racing away. When I hear the demos we made in those days, I find myself thinking, “For heaven’s sake—give that drummer a valium!” (Or a metronome.)

The spectacles on the optician’s sign remind me of the eyes on the billboard in The Great Gatsby, which Fitzgerald used as a symbol for an impassive onlooker, a remote, uncaring deity, seeing all, changing nothing. “The stars look down.”

To any drummer who has sweated over a particular set of drums, they represent another kind of time machine—like a classic violin or guitar, a part of one’s life. Still, I don’t get emotional about my old drumsets, and have given most of them away.

Happily, the Rogers are still in the possession of my friend Brad, who has restored them beautifully, stripping off the cheesy chrome wallpaper to reveal the classic gray ripple finish. A couple of years back I had the opportunity to play them again, in Brad’s basement, with him playing guitar, and we had a fine time.

No, I didn’t feel transported into the past, but it was fun to share a piece of it. And I wished I could have communicated a few observations to that kid who used to play those drums, so many long years ago. Even just to tell him, “Your ‘time’ will come.”

Going back even farther in the Wayback Machine—early 1968 is my best guess—this shot is a kind of miracle. Amazing that it was taken at all, and that it survived, got passed around, and made its way to my mailbox (thanks Joe) more than forty years later. “Garnet’s Head Shop” is the scene, in a former barber shop near the intersection of St. Paul and Geneva Streets in St. Catharines (and right near Ostanek’s Music Centre, my other favored hangout in those days).

Garnet, second from the right, later went even farther into outlaw territory, becoming a biker gang leader, while the future me is in the middle, fifteen-going-on-sixteen, girlfriend Debbie behind me, beside her best friend Linda, whose fringed jacket I was wearing—with flood pants and penny loafers, retina-bruising T-shirt, and unruly bangs. I am captured midway between geek and freak, I guess. Behind the girls is Norbert, our token U.S. draft dodger, and popular guide for people taking their first acid trips. This single image could be a photo-essay from the pages of Life.

All kinds of time travel in this shot, too—past, present, and future. The car is the actual time machine, a 1964 Aston Martin DB5. It evokes an era, the early ’60s, I didn’t really live through, as an adult (I was twelve when it was made), but even today it represents a purity of driving involvement and mechanical art to which I certainly aspired. In its day, the DB5 was the ultimate Grand Tourer, hand-crafted, powerful, luxurious, and elegant (Italian styling allied to the British “feel” for engineering). After being featured in several James Bond movies, beginning with Goldfinger (1964) and continuing to Casino Royale (2006), the DB5 became known as “The Most Famous Car in the World” (though the first Aston Martin I remember seeing a photograph of as a boy was an earlier model, the DB Mark III, which was actually Bond’s car in the Goldfinger novel).

As a general thing, I try to avoid talking about the material things I have been fortunate enough to acquire, not wanting to seem to brag—and definitely not wanting to arouse in others the evil worm of envy. One psychologist theorized that the possession of material things was a prop to make you feel good about yourself—but I thought that theory went two words too far. For me, owning a fine car, a fine watch, or a fine set of drums just makes me feel good, period. Some owners of old cars like to brag about how much attention their pride and joy receives—but I consider that a downside. Sometimes I wish I could press a button and make my DB5 look like, oh, a Prius—not to arouse envy, or even notice, in passersby.

For some, the fantasy might be that if you can afford to buy a beautiful old car, then you could just drive around in it, looking surpassingly cool.

Oh no. Nothing is that easy. An old car—especially an old English car—will test you.

You have to man up to that challenge, and become engaged with the machine. I suffered through many “adventures” with that DB5 (recalling the female rally driver’s comment, after her car skidded off of a snowy road and rolled onto its roof: “Adventures suck when you’re having them”). Breakdowns, overheating, having to refuel without turning off the engine (it wouldn’t start when hot), flatbed recoveries, and roadside repairs with Swiss Army knife and emery board were part of that adventure.

After three years, including a couple of concert tours and lengthy service visits that kept me from driving the car, the “testing” has stretched over twelve thousand miles, and we’ve been through all that now—me, the car, and master mechanic Ken Lovejoy, who loves the car nearly as much as I do. His shop is “conveniently” located 350 miles from my home, up in the Bay Area, but that has allowed for many memorable road trips, often with my friend Matt Scannell, who also loves cars and journeys (and gosh, we make each other laugh), and occasioned some “adventures,” too. An overnight in Big Sur, one of my favorite parts of California, is a bonus—breaking down there, not so much.

Having invested in mechanical rebuilds and upgrades, and survived the adventures, now I have a reliable more-or-less daily driver (proved by the cloth grocery bags in the trunk—or, “boot”). More old cars perish from neglect than from overuse, and the more I drive it, the better it runs.

As for the reward for all of that effort and expense, it can still best be expressed by the time machine of a song—“Red Barchetta.” Written thirty years ago, set in a future dystopia that still looms in the fears of paranoid petrolheads—a time when motorcars, and motorcycles, are outlawed—its description of driving pleasure remains as evocative as I could hope to express now.

Wind in my hair

Shifting and drifting

Mechanical music

Adrenaline surge

Well-weathered leather

Hot metal and oil

The scented country air

Sunlight on chrome

The blur of the landscape

Every nerve aware

The idea of rewriting those lines, vis-à-vis the DB5, came to mind:

Wind in my hair

[Windows always open, ’cause there’s no AC]

Shifting and drifting

[Slipping and sliding on those skinny bias-ply tires]

Mechanical music

[Vroom-vroom—ka-ching!]

Adrenaline surge

[The clutch pedal just went to the floor and stayed there]

Well-weathered leather

[Need to repair passenger seat-back]

Hot metal and oil

[Is that temperature gauge creeping up too high?]

The scented country air

[Windows always open, ’cause there’s no AC]

Sunlight on chrome

[Note to have the door handles redone]

The blur of the landscape

[With due regard to the California Highway Patrol—and at night, the failed speedometer light—requiring an occasional check with Maglite]

Every nerve aware

[Is that temperature gauge creeping up too high?]

A modern car—like perhaps the DB5’s present-day descendant, the DB9—is another kind of time machine: a glimpse of the future. So far superior in power, handling, and sheer competence, the DB9 is a space ship—yet one that would be recognizable to Jules Verne or H.G. Wells, its streamlined aluminum hull comfortably upholstered in wine-colored leather and polished walnut.

In the previous photograph, I was driving the old DB5 home from Drum Channel, south on the Pacific Coast Highway near Zuma Beach—with California fan palms tossed in the onshore breeze—after a hard day’s drumming. Next to Zuma Beach is Point Dume, pronounced “Doom” (both Chumash Indian names, like Malibu and Topanga), and that always reads to me like a cryptic kind of cautionary tale—Zooma to Doom.

The first three weeks were just me and Lorne “Gump” Wheaton, my drum tech for almost ten years. Playing through the songs, learning them in some cases, revisiting them in others, I was also building up my calluses, and my stamina, to “performance grade.”

And what a clockwork complication of thoughts revolved in my brain during that one-hour drive up to work and back—“Remember that fill in ‘Camera Eye,’” “Have a listen to that part of ‘MalNar’ and get it right,” “Try that Latin bass-drum ostinato under the African samples for the solo.”

During the first three days Gump and I were joined by the band’s longtime keyboard and sampling consultant, Jim Burgess, and he and I auditioned about 200 sampled sounds—industrial, ethnic, manufactured, and electronic—looking for new material for my drum solo. I selected three different arrays of sounds, tonal soundscapes, that I improvised on every day, looking for shapes and patterns that pleased me, and working out a new “architecture” for this tour’s solo.

One interesting insight: among those 200 sounds were arrays of drums from West Africa, India, Asia, and the Middle East. I was curious about that last category, because I never think of Middle Eastern music as particularly rhythmic. And sure enough, all of those drum sounds were flat, toneless, and uninspiring, as compared with some of the West African ones, or the Indian tablas, which expressed such a complexity of tone and timbre. Musical history states that only European composers ever developed harmony, but I remember mentioning to Jim about a drum from Benin—its sound did contain harmony, as does the West African djembe, now that I think of it, a range of pitches that give voice to far more power of communication than the dull “thud” of the Middle Eastern drums.

Over lunch one day with some of the Drum Channel guys, and visiting percussion master Alex Acuña, I suggested that perhaps Islamic extremism had arisen from just that unfortunate deprivation—a lack of decent drums.

“Why do infidels have all the good drums? They must die! Derka, derka, muhammed jihad!”

This photo was taken at Blackbird Studios in Nashville, on Tuesday, April 13, 2010, while I was being the “time machine”—recording drum parts for two new Rush songs. Alex, Geddy, and I had put them together over the winter and spring, mostly by long distance (Geddy e-mailing me from Toronto to report on his and Alex’s progress in his home studio, and to request lyrical alterations), even as we were planning our “Time Machine” tour. We had never done anything like that before—write, arrange, record, and release just two songs, instead of a whole album—then go out on tour and play them, along with what we thought was an inventive selection of our older songs. But the real-time time machine—life—has brought many changes to what used to be called the “music business,” and we thought, “Why not?”

I was using the Snakes and Arrows kit for that session, and now, rehearsing for the tour at Drum Channel, I was playing a mish-mash of a setup, based on the “Hockey Kit,” that Gump had successfully assembled for me to work with—because just around the corner, at Drum Workshop, a spectacular new drumset was under construction, down to the final details of finishing and assembly. Sometimes Gump and I took a “field trip” over to the factory, to check on its progress.

As I played through the old songs the three of us had agreed to resurrect for the “Time Machine” tour, some of which I hadn’t played live in ten years, twenty years, or ever, it occurred to me that the ultimate time machine might be a song. What else can immediately take you to a particular moment in time—an indelible memory that overwhelms you with its completeness? Smells are famously powerful memory stimulators, and—as we have seen—images of the past can have an intense effect of revitalizing the olden days. But when it comes to really taking you somewhere, there is nothing like a song.

And it doesn’t have to be only about memory. It happens that the two songs we recorded that day in Nashville are detached from the past, rooted in the present, and pointed toward the future. Because they are the first two parts of what we envision as an extended album-length story, they truly are a work in progress, and thus a glimpse of our own future. Some sneer at the notion of “progressive” music, but I am pleased to note that I’m still progressing—several elements of my drum parts in those songs contain discoveries in technique and knowledge that I have only acquired in the past couple of years—studying with Peter Erskine, playing the Buddy Rich tribute concert, recording “The Hockey Theme,” and just generally moving through time, as a drummer.

(No one moves through time like a drummer!)

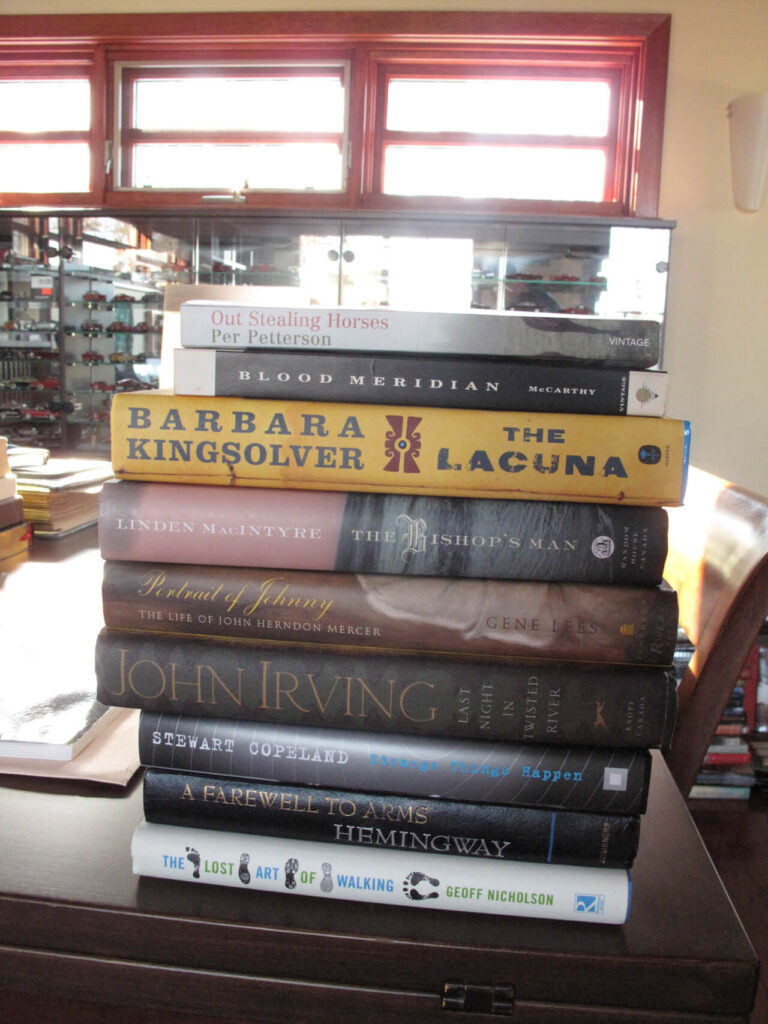

Books, I think, are a different kind of time machine. Instead of reminding you of a lost world, they create one for you. More personal, more intimate—unlike movies, say, the world you experience while reading a book has been lived and envisioned entirely from the inside, and its contours are yours alone.

This pile of volumes represents my reading list for ten days in late February, a solitary winter retreat that was somewhat marred by bad weather, and being under the weather, so I had nothing better to do than lie by the fire and turn the pages. (If there really is a heaven . . . )

Obviously these titles are all future material for Bubba’s Book Club, but just looking at the spines now, the stories, images, scenes, characters, and moods conveyed to me, as the reader, are near infinite. A treasure chest, a time capsule, a time machine with access to so many worlds.

“Oh, the places you’ll go,” said Dr. Seuss, and for this traveler, there’s no way I’d rather go than by motorcycle. And it too can be a time machine, taking me to places where the past seems alive, but carried forward into the present. And that present—the day’s weather, scenery, wildlife, and humanity—is experienced with raw nerve-endings.

As for the future, it’s always right there—the road ahead of my front wheel.

But so far humans don’t really have a way to send ourselves into the future—with the sole exception of transmitting our DNA through the delightful medium of babies. Some might say creating something beautiful that endures is a kind of immortality, but even if a story or a song survives into the future, it can’t take you with it.

Baby can do that.

Carrie and I had welcomed Olivia into the world the previous August, and I was surprised to find that even as our home was caught up in a tempest, a whirlwind, a tornado—which carried us not to Oz, but to Planet Olivia—I was still inspired to work. Stories, book reviews, recipes, days of drumming labor on “The Hockey Theme,” and a whole album’s worth of lyrics, all were created in moments stolen from the compelling priorities of helping to care for baby, and feeding the family (indirectly in Olivia’s case, but still. . . ).

No doubt part of that urge was a result of the hardwired male conditioning to be the “breadwinner,” to bring home the bacon (as well as “fry it up in a pan”), but some of it was a response to the muse.

We all revolved around Planet Olivia, orbiting like weather and communications satellites, fixed by her gravity, and by her radiance. Psychologists tell us that nearly everything men do is in some way related to the primal desire to “impress chicks,” and that reflex seemed to be working its mojo on me. This little bundle of bittersweet joy was telling me to quit messing around and get to work.

But first, let’s play and read books.

And so we did.