Certainly at this point, after being together for almost thirty-eight years (and being around a decade or two before that), Alex, Geddy, and I have reached our “mature years.” However, we have arrived there hot and sweaty, sliding into third, as a working, touring band. Like our well-tempered friendship, our dedication and inspiration remain strong, combined with hard-won experience and knowledge—acquired over twenty studio albums, and perhaps most of all by playing thousands of live shows.

In December, 2009, the three of us met to talk about the coming year. While eating and drinking and laughing a lot, as we do so well, we discussed all the possible projects we could launch in 2010. We could start working on a new album, or we could launch a major tour. Fools that we are, we ended up doing both.

Perhaps the wine can be blamed for that—and for our increasingly ambitious talk of creating some new music that was “a little more extended.” In turn, the wine seemed to embolden me (In Vino Veritas) to tell the guys about my idea for a fictional world, a possible setting for a suite of songs that told a story. (The first song, “Caravan,” contains a key line: “In a world where I feel so small, I can’t stop thinking big.”)

My friend Kevin J. Anderson was among the pioneers of a genre of science fiction that came to be called “steampunk”—a more romantic, idealistic reaction against the “cyberpunk” futurists, with their scenarios of dehumanized, alienated, dystopian societies. Our own previous excursions into the future, 2112 and “Red Barchetta,” had been set in that darker kind of imagining, for dramatic and allegorical effect. This time I was thinking of steampunk’s definition as “The future as it ought to have been,” or “The future as seen from the past”—as imagined by Jules Verne and H. G. Wells in the late nineteenth century.

The guys seemed receptive to the idea, and I started working on a story and some lyrics set in “a world lit only by fire” (title of a history of medieval times by William Manchester). Influences were inevitable, but still unexpected to me—a lifetime of reading distilled into a dozen scenes, and a few hundred words. The plot draws from Voltaire’s Candide, with nods to John Barth’s The Sot-Weed Factor, Michael Ondaatje and Joseph Conrad for “The Anarchist,” Robertson Davies and Herbert Gold for “Carnies,” Daphne du Maurier for “The Wreckers,” Cormac McCarthy and early Spanish explorers in the American Southwest for “Seven Cities of Gold.”

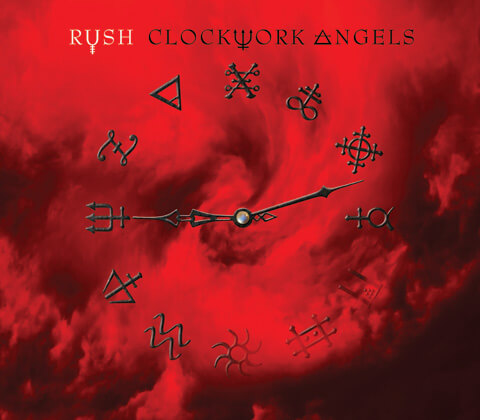

This “one of many possible worlds” is driven by steam, intricate clockworks, and alchemy. That last element occurred to me because I was intrigued by Diane Ackerman’s use of a few alchemical symbols as chapter heads in An Alchemy of Mind. They seemed elegant, mysterious, and powerful. Soon I learned about an entire set of runic hieroglyphs for elements and processes, and as with the tarot cards for Vapor Trails, and the Hindu game of Leela for Snakes and Arrows, I became fascinated with an ancient tradition. As the lyrical “chapters” came together, I chose one symbol to represent each of them, for the character or mood. Those would end up arrayed on the cover clockface, as first used on the “Caravan”/“BU2B” single in early 2010. Since then they have shifted a little, as the story has grown, but you can find brimstone at one o’clock for the faith-bashing “BU2B,” gold at six o’clock for “Seven Cities of Gold,” earth at eleven o’clock for “The Garden,” and so on. (The “U” in Rush stands for “amalgamation.”)

Early in January, 2010, I was able to send a bunch of lyrics to Alex and Geddy in Toronto. They got together in Geddy’s home studio, just “messing around,” jamming and seeing what came out.

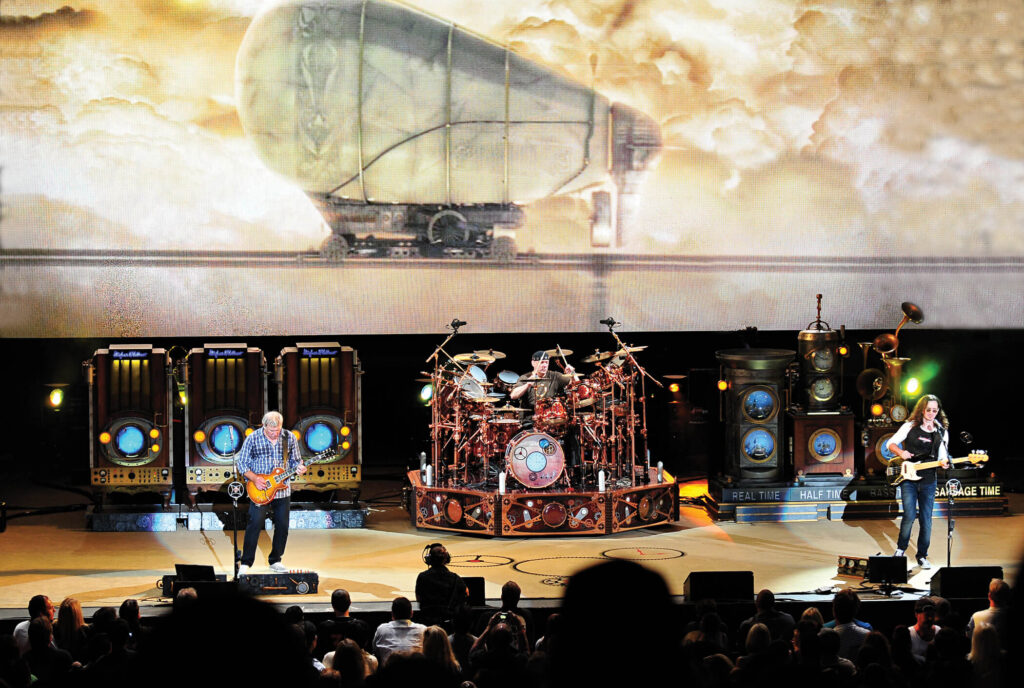

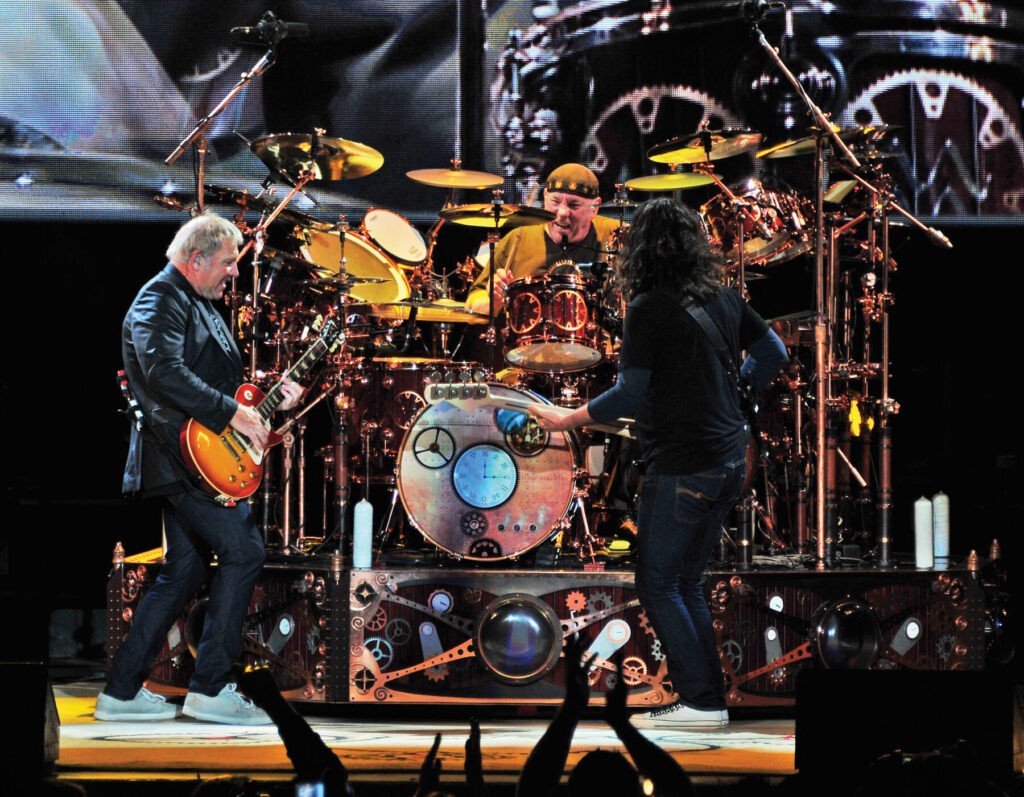

Improvisation was a major theme for the band leading up to this album. In live performance, during the Time Machine tour in 2010-11, we were each aiming to be more spontaneous in our “spotlight moments,” and it thus became a shared ambition, and a spirit that carried into every element of this recording.

For the first time, I started the lyrics with the proverbial clean sheet, rather than my usual routine of riffling (and riffing) through the file of lines and titles I have collected over the years. (I call that “The Scrapyard.”) Likewise, the music was composed in that elemental way—Alex and Geddy in a basement studio with guitar and bass, riffing and strumming away, and recording everything they played. Alex had put together one collection of ideas that turned out to be most of the song “Clockwork Angels,” and as soon as I heard its rhythmic feel, which was so different for us, my response was “I want to play to that!”

In early 2011, before the second half of the Time Machine tour, they got together to try to get going on the writing again. Having a bit of a struggle, they seemed to spend more time drinking coffee and making stupid jokes—except for a couple of furious jams that, when reviewed later, turned out to be the foundations of “Carnies” and “Headlong Flight.”

As a general thing, Geddy would listen back to their jams and note the most compelling bits, then assemble them into a random arrangement. Only then did he turn to the pile of lyrics I had sent, to see if anything wanted to go with that music. Sometimes, as with “Seven Cities of Gold,” there was an immediate spark of connection. As Alex relates, “We talked about having a raucous beginning that related to the middle ‘solo’ section, all feedback and crazy, and as the song evolved it took on the appropriate character; entering the city with all the wild, dangerous sensory experience it offers.”

Other marriages of music and words were more laborious, and launched a flurry of emails between Geddy and me. Rapid-fire exchanges discussed adjustments to lines and phrases, passages deleted and new ones added, all on the fly, so that even the final shape of the lyrics was more-or-less improvised. Later I would try to stitch the remains together in a way that still expressed what I had intended—and that part wasn’t easy. I had a complicated story to tell, with, like, characters and ideas and stuff.

Some of Alex’s finest solos also date from the demo stage: offhand “place-holders” that turned out to be unbeatable. “Clockwork Angels” is one example like that, as is “The Garden”—a few takes recorded casually and assembled into an improvised performance that remains his personal favorite.

As the songs were gradually assembled from spontaneous moments, we worked out the arrangements together. Then Alex (our musical scientist) would give me a demo with two versions of the song: one with the drum-machine patterns he had programmed for their writing and arranging purposes, to give me a sense of how they perceived the drum part dynamically (plus Alex often has some good non-drummer ideas that inspire me in alternative directions), and one with just a click track.

The first two songs, “Caravan” and “BU2B,” were recorded before the Time Machine tour, in April, 2010, and several of the other songs had been written by then. After taking a break to rehearse for that tour, and play eighty-one shows in North America, South America, and Europe (some break), we got together again in October, 2011, at Revolution Recording in Toronto. Alex and Geddy worked in the small studio there, continuing the songwriting and arranging.

To keep the writing fresh, one day they even tried switching instruments—Geddy on guitar and Alex on bass—and they turned out a richly melodic song called “The Wreckers.” They joked that playing the “wrong” instruments had turned them into the Barenaked Ladies. (I happened to run into Ed Robertson around that time, and he had a good laugh about that.) But once we switched to recording mode, it was back to the “same old us.”

In the big studio, my drums were set up and ready for me to start learning new songs. Around the drums, master engineer Rich Chycki had prepared the recording environment, so we were “ready to fly.” Taking off my lyric-writing cowboy hat (I have pointed out before that I find it hard to take myself too seriously when I am wearing a cowboy hat), I would put on my drumming hat (an African prayer cap—which has equally perfect resonance).

My drum parts were created in a completely different fashion than ever before. For the past few years I have been working deliberately to become more improvisational on the drums, especially in my warmups and solos, and these sessions were an opportunity to attempt that approach in the studio. It began with “Caravan” and “BU2B,” which were fairly well organized before recording, but featured a number of spontaneous moments. In these more recent sessions, I played through each song just a few times on my own, checking out patterns and fills that might work, then called in our coproducer, Nick Raskulinecz—“The Mighty Booujzhe.”

(A reminder about that nickname: Nick likes to suggest outrageous fills for me to play, and he will mime them with wild physical gestures and sound effects: “Bloppida-bloppida-batu-batu-whirrrrr-blop—booujzhe!” That last being the downbeat, with crash cymbal and bass drum.)

So . . . Booujzhe stood out there in the room with me, facing my drums, with a music stand and a single drumstick. He was my conductor, and I was his orchestra. (I later replaced that stick with a real baton.)

The enthusiastic “Booujzhe-ness” before me energized and inspired me, and he also offered many good suggestions between takes. We quickly hammered out (well, I did the hammering!) the basic architecture of the part, and demonstrated the key element of collaboration—together we elevated it.

Now . . . Rush songs tend to have complicated arrangements, with odd numbers of beats, bars, and measures all over the place. These latest songs are no different (maybe worse—or better, depending), but the baton of Booujzhe would conduct me into choruses, half-time bridges, and double-time outros and so on—so I didn’t have to worry about their durations. No counting, and no endless repetition of each song just to learn those things—that was a big part of what allowed me to be so spontaneous.

In past years I might have spent several days developing and refining a drum part, but this time it was just a matter of hours “from zero to hero.” I like to think a listener can sense that difference—will share the tension and release of a guy going way out there, playing something he has never attempted before, and only just making it back to “one.” Chances are that moment only happened once—but that was enough. In turn, Geddy’s bass parts and Alex’s guitars were added without too much time spent learning, but getting straight to the playing. Booujzhe was their conductor, too, coaching and inspiring Geddy, Alex, then Geddy again (vocals) with suggestions and encouragement, to ever higher levels of absurdity.

(After all these years together, we have learned to be comfortable recording separately—it allows everybody to focus on one part at a time, and experience has taught us that we play the same—to each other—regardless.)

Typically, there was one “trouble child.” Out of all the seemingly more complicated songs, the music for “Wish Them Well” was written and scrapped twice, and the song was almost abandoned. But Geddy liked the lyrics enough to keep trying (thank you!), and the third version pleased everyone.

That song also put Booujzhe and me to a lot of trouble over the drum part, much more than any other song except “Headlong Flight”—that one for its perverse complexity, rather than the exacting simplicity of “Wish Them Well.” Booujzhe and I spent many hours trying out different basic patterns, and juggling their arrangement.

(The guys always laugh when I come out of the studio grumbling, “I hate that stupid ignorant song!” [Add expletives to taste.] They laugh because they are the ones who made it that way.)

“Wish Them Well” was equally elusive vocally—or at least lyrically. The day Geddy and Booujzhe recorded that vocal in Toronto, I happened to be at home in California, and all day we exchanged texts and emails over the tiniest of alterations, line by line, sometimes word by word. Ultimately it turned out very well, but I admit I still have a bit of a grudge against that song.

On the bright side—even the brilliant side—one very special aspect of this project is the lush and exotic string arrangements, by David Campbell. One January afternoon at Ocean Way Studios in Hollywood, I stood in the control room listening while the strings were being recorded. It occurred to me that all songwriters should experience the sensual delight of hearing their songs performed by an accomplished string section. For example, when these virtuoso artists on violin, viola, cello, and double-bass executed David’s plangent orchestration for “The Garden,” there was not a dry eye in the studio.

Finally Booujzhe took over the mixing chair, and entertained us by miming each of our parts note-for-note, with appropriate gestures and facial expressions. When he had his fist up to his mouth as a microphone, emulating every phrase and nuance of Geddy’s vocal, sometimes he raised his little finger. “My wireless mic,” he explained. He had switched to “live performance” mode.

Another long-time goal took root in August, 2010, on a day off between shows at Colorado’s Red Rocks amphitheater. For about twenty years, I have been friends with the previously-mentioned author and pioneer of steampunk, Kevin J. Anderson, and all that time we have discussed doing a project together to combine lyrics and prose. Kevin lived nearby, and led me on a hike up Colorado’s Mount Evans (14,265 feet), during which we started workshopping a prose version of the Clockwork Angels story. A year and a half later, Kevin would do the “heavy lifting” on its novelization.

So once again, collaboration proves joyful, and elevates the art. This project has been sparked by many sources of flint and steel, and one quality shared by everyone involved might be called “a fevered imagination.” That temperament, burning slightly hotter than what passes for “normal,” also describes art director Hugh Syme—who is serving a life sentence as my graphic arts collaborator. Hugh brings his own febrile dreams to the Vision Quest, and whatever I can visualize, he can realize. The two-year (literally elephantine) gestation period of this album allowed Hugh time to generate a series of beautifully evocative illustrations to accompany the story—the words and music.

One more oblique connection: During the filming of my most recent instructional DVD, Taking Center Stage: A Lifetime of Live Performance, I found myself talking about playing our older songs in concert year after year, and something occurred to me about Rush songs that I had never realized in all our thirty-eight years.

See, for the most part, Rush songs weren’t made with the intention of being listened to on the radio, or in the car, or with earbuds. They were made to be played—by us! (Good title, “Made 2 B Played.”)

Thinking of even a few older examples—“The Spirit of Radio,” “Limelight,” or “Subdivisions”—the arrangements are detailed and dynamic, intricate and challenging, and build toward a rock-concert climax. None of that was ever discussed among us, but all instinctively, our songs, arrangements, and playing exemplified a live-performance piece. It is certainly those qualities of challenging technique and in-the-moment excitement that keep those songs fresh for us all these years later. Like Booujzhe, we raise our little fingers and we are in “performance mode.”

That built-to-be-performed quality is clearly evident on all of the songs on Clockwork Angels, too. Like the nineteen albums that have come before, these songs are “Made 2 B Played,” again and again for years.

And, if the fates allow, they will be . . .