Then into the second verse, which opens with a line inspired by a Swahili saying I had collected in my African travels. It still often resonates with me:

“Hyena says, ‘I am not lucky, but I am always on the move.’”

Oh, that echoes deep for me, year after year. Like so much African wisdom in the oral tradition, the insight is as chiseled and nuanced as anything by Aesop or Aristotle.

Well, I may not be too lucky, but I’m always on the move

Now I’ve got nothing to lose, I’ve got nothing to prove

One thing I have learned — you can’t tell yourself how to feel

Surrender to the notion the irrational is no less real

— On the last lonely day

So many things I’ve buried there

In ghost towns and abandoned mines

So many things I’ve carried there

That I will leave behind

— On the last lonely day

An observant fan of songs by the Guys at Work will notice that I recycled the “can’t tell yourself how to feel” idea into another song on Vapor Trails, “How It Is,” and the “lowest low and the highest high” into “Ghost Rider.”

Because salvage!

(I actually call my file of leftover lyrical ideas the “Scrapyard.”)

This excerpt from a letter to Brutus in Ghost Rider describes that first ascent, starting with the motorcycle approach.

And that was just to get to the trailhead, at 8,000 feet. Then seven miles on foot up to the summit, through ascending ranges of sage, then juniper, then pinyon pine, mountain mahogany (another tree, like the giant sequoias and ponderosa pines, that needs fire to germinate), limber pine above 9,000 feet, and finally the ancient bristlecone pines, above 10,000 feet.

The summit itself was pretty much bare, jagged rock (though it felt pretty comfortable to lay on by the time I got there), with only a few grasses, but the view, of course, was stupendous. The whole valley so far down, the white floor around Badwater (the part they call the “chemical desert”), and the oasis of Furnace Creek just a tiny green smudge. And far below to the west, Panamint Valley, with its brown furrowed mountains, heaping of sand dunes at one end, the highway across it invisible except to my imagination, and somewhere way over there, Father Crowley Overlook.

Now, though, I’m tired and sore. Coming down was once again nearly as tough as going up—except it was easier to breathe, at least. At one point I was enumerating my pains as I walked: neck, shoulders, back, lower back, hips, thighs, hamstrings, knees, calves, ankles, and, especially, feet. (Waaah!) But I made it without needing a helicopter rescue.

This time, on April 9, 2014, I rode up the graded gravel track to the Wildrose trailhead, beside the Charcoal Kilns (see “December in Death Valley,” in Far and Away). The road was dry, but patches of snow remained among the pinyon pines to either side. (Death Valley has a double treeline—the usual upper limit beyond which trees will not grow, and a lower line, defined by heat and dryness, below which no trees live.) Climbing from there, a sign warned that high-clearance four-wheel-drive might be required. The track became narrower, steeper, and badly rutted, with solidified mud and gravel studded with larger rocks. I switched the motorcycle’s traction control setting to “Enduro,” to allow for some wheelspin, then stood on the pegs and bounced up another mile or so. I parked near the Mahogany Flats campground, at 8,113 feet.

Changing from riding gear into hiking clothes and shouldering my daypack, I stopped at the register for the Telescope Peak trailhead. It was like a raised metal desk with a lid, and inside was a pad of paper and assorted pens and pencils. The most recent entry, dated two days before by “two adults,” said “We summited!” I took that as encouragement. Not an omen, but a glimmer of . . . possibility.

I picked up a pencil and signed in below.

4/9/14Bubba9:10

A couple of miles later, maybe a thousand feet higher, I rounded a point among the limber pines and saw the above view of distant Telescope Peak. And all that snow. The expression in my self-portrait echoes the “Are You Serious?” theme used before about cross-country skiing self-portraits, skimming downhill in a blizzard at zero Fahrenheit. This time I mentally added an expletive to that rhetorical question—for extra emphasis.

Because it sure didn’t look good.

(Despite all of that precipitation apparent just above Death Valley, the valley floor had received just one third of an inch of rain that year—less than two inches since the previous spring. Whatever moisture got by the barrier of the Sierras to the west, the Panamints intercepted, leaving Death Valley in a double rainshadow.)

Without giving it much thought, I decided to set out and keep going upward as long as possible, then turn around. Hard to quarrel with that plan—except perhaps with the debatable line of what defined “possible.” Farther along that difficult trail, I would discuss that line with myself more than once—wondering if perhaps I had reached it.

Around this point I looked up and saw three tiny figures coming the other way—animals, I thought at first, but they turned out to be three hikers, young guys. I gave them a wave and a smile, but did not pause in my determined march. Two of them seemed to be together, maybe Europeans, for they wore sports clothes—like soccer or rugby uniforms, and athletic shoes—rather than hiking gear (yes, I’m the fashion police when it comes to backcountry hiking, cross-country skiing, or motorcycling), and carried no packs. Where the snowfield ended (for them—began for me), the third guy moved wide to pass around us, then broke into a trot. He appeared to be a Trail Runner (I’m sure he capitalized and adopted the name in his social media). Below his man-bun and poetic facial hair, he was dressed collar to cuffs in tight lycra, with a yoke-like affair over his shoulders carrying bottles of water. He was wearing those funny little shoes with the separate toes (I noticed from his tracks in the deep snow after that—must have been cold).

Later, following their tracks upward, smiling darkly at the toe-shaped ones, I saw where Trail Runner had fallen. The thin, waffle-patterned sole and toes had slipped down the icy surface a fair distance, ending where his curled-up body shape was pressed into the white slope, shoulders and knees facing downhill. Snow can be treacherous—dangerous.

Apparently there is some debate about how many words the Inuit actually have for frozen water, but as a Native Canadian, I can attest that snow has many, many different manifestations upon the Earth. Powdery soft to rock-hard, blinding white to shadowy blue, fairytale woods to gray city slush.

A few stories ago, I was grappling with some large, slippery concept—something do to with the way people’s impressions of an alien landscape, like, say, “the desert,” or “the mountains,” was always simplistic and reductive. I introduced the existential notion that “Nothing is ever just one thing.”

Later I was surprised to see the great New York Times columnist Maureen Dowd use that exact phrase, and I wondered, “Hey—where’d she get that?” Then I learned that a master writer got there before either of us: Virginia Woolf, in To the Lighthouse, “For nothing was simply one thing.”

Well, yeah. Because complicated.

Long digression short, to say that nothing is simply one thing is abundantly true of snow.

Where the trail followed the ridges and saddles (one with the great name of Arcane Meadows—“secret, mysterious, known to only a few”), I could either sidestep the drifts—some up to two feet deep—or labor through them, as I saw previous hikers had done. However, that surface was not reliable; sometimes I could make a few steps on top of the drift, then suddenly one boot would sink deep, tripping me up and needing extra effort to get out and move on. Breathing was difficult in the thin air, so every lungful was guarded and precious. (Somewhere I learned only to think about the exhale, because you’re going to breathe in naturally anyway, and that always works for me.)

Another hazard was that after a few such deep plunges, the loose snow gathered around my boottops and wicked down into my socks, until they were soaked through. Now I worried about blisters—I still had a long way to walk, even if I turned around before the top.

On steeper pitches, as shown above, I could kick my toes into the softer snow and lever upwards. But occasionally the snow wasn’t soft, but icy and unyielding, and that wasn’t nice to kick. Sometimes I could “herringbone” my boots, edged in and splayed outward, as in cross-country skiing. But with either technique, too many times the snow gave way under my weight, and I would slide back down a step, and that was discouraging. I would have to work harder to regain my balance, often crying out in surprise and frustration, and would lose that precious step upward. Falling was a worse fear, especially around exposed rocks—they were often sharp-edged blocks of gneiss, which could cause a serious injury, especially to a vulnerable knee. Even falling into the yielding snow was tough, because of the effort of struggling up again. I paused often to catch my breath (I mean look at the view!), and altogether it was becoming a challenge on the edge of my determination.

Have I reached that line yet?

Looking upward, the steep snowfield between jagged rocks and weathered trees seemed to rise so high above me. And I couldn’t know if that visible edge actually represented the summit, or if I would arrive there to find another arduous slope of rock and snow. Body straining, my mind grew dim, and fanciful. Maybe I should turn around—hell, I could even claim to have made it, no one would know. Those three guys probably hadn’t made it all the way up (I hadn’t asked, not wanting to be discouraged). Perhaps two days ago, when the two hikers wrote “We summited!” in the trail register, they had lied. Or maybe that day the snow had been easier, firmer underfoot on those steeper pitches. All I knew was, this was getting to be . . . too much.

But I kept climbing, one foot in front of the other, for a long time. (I am very bad at giving up—must work on that.) By then, the hours had become an arc of effort—it felt like I had started the hike straining for the first couple of miles, then settled into a steady groove for a while, but now—surely toward the end—it was punishingly hard again. That reminded me of other such ordeals, like what bicyclists call a “Century,” where you ride a hundred miles in one day. In the ’80s and ’90s I had done a number of Centuries, and always found that the first ten or twenty miles seemed hard, and it was impossible to contemplate the entire distance from that tender beginning. Then a groove would take over for sixty or seventy miles—the endorphins and dopamine, I guess—erasing time and distance. Those miles fell behind easily. Then, as if in withdrawal from those sustaining drugs, the last ten miles crashed down on me. Weariness and discouragement turned those final miles into a dark slog.

Sometimes cyclists choose to do a “Metric Century” instead, meaning a hundred kilometers, or sixty-two-point-five miles. I smiled to think that I was almost a metric century, at sixty-one-point-five years, so no wonder this climb felt so tough. The last time I had done it was fifteen years ago, after all, when I was a mere forty-six—a child!

Compared to the ancient bristlecone pines that clung to the highest elevations around me, we were all children. Unborn cells, really. Apart from creosote colonies, bristlecones are the oldest individual organisms on Earth—as much as 5,000 years, dating to the time of the pharaohs. The example pictured above, with the Panamint Valley and the white line of the snow-crested Sierra Nevada behind, is actually still alive, despite being cruelly blasted by millennia of harsh weather and lightning.

Finally, finally, finally, I crested the peak. It was a “false summit,” but I remembered that a short saddle led to the actual top. (I didn’t see any recent tracks in the snow there, so wondered if the three young sportsmen had turned around a little too soon.) The actual summit was a roughly circular pedestal of barren, square-faulted rock, with only a few hardy grasses in the cracks. An old metal ammunition box rested at an angle, and you could leave a note if you wanted. I didn’t.

Because tired.

Telescope Peak was climbed and named in 1861 by Dr. Samuel George. He said he could see so far that it reminded him of looking through a telescope. Nicely played, Doc.

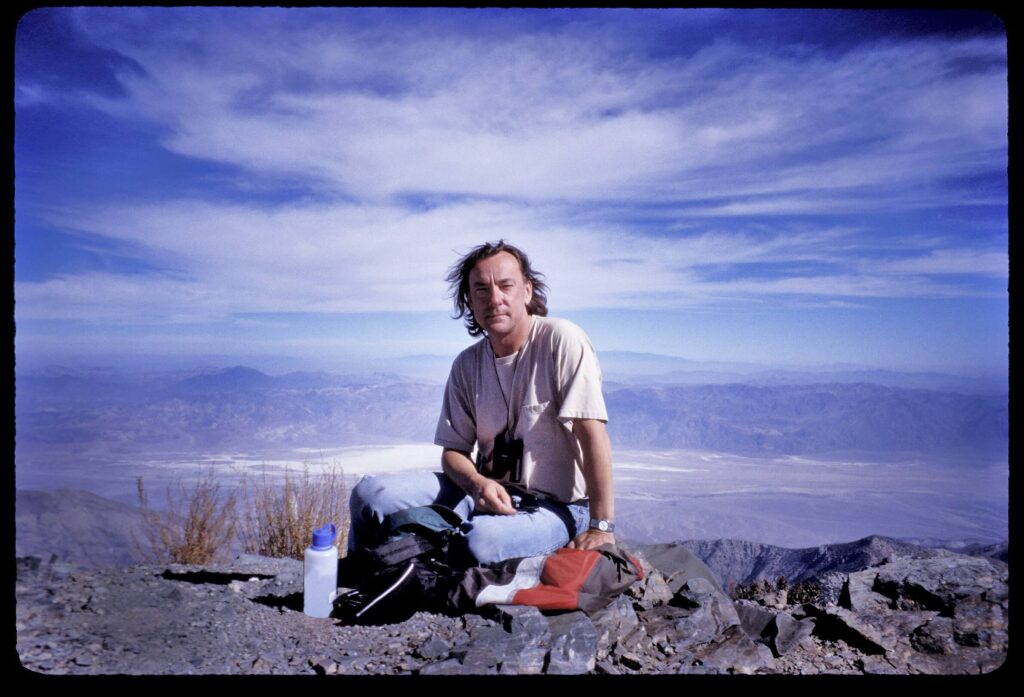

I eased myself down onto those sharp-edged rocks, and stretched my legs out toward a lingering snowdrift, facing down over Death Valley. One slab of rock offered a decent angle, and I leaned back against it, feeling nothing but relief. (Though always with an undercurrent of anxiety, still facing the long, perilous descent.) Taking my time, I looked around at the 360-degree view, drank some water, ate an apple, a stick of cheese, and a chocolate wafer bar.

My feelings were certainly “elevated,” though hardly ecstatic—I knew I still had a long hard walk back to my motorcycle. But I had made it to that summit. Even at the ripe old age of a Metric Century. And that did feel good.

The ammunition box came in handy as a camera stand, for a self-timer shot of my summit triumph.

Taking up my pack again and heading down, the steep, snowy pitch was nearly as hard to descend as it had been to climb, and just as dangerous. Mostly I followed my previous trail, now kicking my heels into the snow, and traversing across the steepest patches. Sometimes I held onto a rock, or grabbed at a limber pine branch (great smell they have, as do the high-elevation sages), feeling my legs aching and occasionally quivering with the strain. I plodded, slogged, and marched across the saddles, the wind driving in from the west in powerful gusts that pushed me sideways. (People on mountain ledges get killed that way, too—blown off by unexpected winds. Good thing I was “well-weighted.”)

Mostly my eyes were down on the trail, watching my footing (that’s why bandanas are my preferred hiking headgear, to absorb sweat while allowing me to see ahead), but occasionally I paused and stood looking around at the view—west to Panamint Valley and the distant Sierras, east over the pale expanse of Death Valley, the dark Funeral Mountains, and the faroff, snow-tipped White Mountains in Nevada.

My thoughts churned away, but at nothing in particular. I have always found that when I am exerting maximum will, my thinking is not imaginative. (Somewhere Isak Dinesen wrote about the reverse conclusion: “. . . the freedom of the artist, who has no will, who is free of will.” That explains a lot about tragic artists, that’s for sure.) Exercising in a gym, riding a bicycle or motorcycle, or hiking in the mountains has never produced a creative thought for me (drumming is the only activity in my life that combines athletic activity with creative thinking—and that’s plenty). Typically, during an ordeal like that hike, the best my mind can do is work at “writing exercises”—trying to observe and put what I see and feel into sentences, then remember it for when I try to write it, to share it.

Dark imaginings of falling and hurting myself badly, or being struck down by some cardiovascular “event,” made me think of hypothermia—as in “dying of.” That reminded me of a word I had just learned, “hyperthymia.” It is basically defined this way: “Hyperthymic people have so much energy, do so many things, and get so much done that it annoys other people.”

Oh dear. Some who know me well will laugh at that—others will be annoyed. Because truth.

In fact, ahem, well, if I do say—it’s so true that I even often annoy myself. Like on that hike, there was a moment when I thought of something simple and important enough that I paused to write it down, “Don’t ever do this again.”

Later I added a joke, “No more suffering on purpose, okay?”

Brother Danny offered a suitable quote (as always) from British mountaineer C. F. Meade:

“Whatever agonies and miseries the sufferer may endure on his pilgrimage to the heights, and however often he may swear never to return there, longing to do so is certain to recur.”

The previous week I spent an afternoon at Drum Channel, borrowing a little drumset in the studio for some casual “explorations.” It was gratifying to learn that my technique remained “ingrained” (I said to Don Lombardi, “The machine still works!”), and that having stepped away from the routine of it allowed me to think in surprisingly fresh ways. It was an enjoyable, rewarding few hours—but after, I thought about doing that every day, like rehearsing for a tour. The idea did not appeal. The same with the 950-mile motorcycle ride to Death Valley and back, and all the packing and unpacking—it did not make me want to go back to doing that every day, like on tour.

But that decision is far in the future—we’ll see which way the wind blows then. Perhaps, as the man said, “longing to do so is certain to recur.”

On that endless march down from Telescope Peak, every time my eyes followed the trail curving far around a ridge ahead, I hoped it would be the last one. But those long ridges went on and on, until I wondered if I had somehow got on the wrong trail. There was only one trail up there—it had just grown longer since I climbed it a few hours before. My body was a tired, aching slave, and my mind was a dark, empty engine of will. I kept going because there was nothing else to do.

(One helpful consolation of old journals and writings is that they can help correct some illusions of memory. Like the common refrain that something hard was ever easy—the truth is that you just forget over time! Recall my list of aches from the ’99 hike: “neck, shoulders, back, lower back, hips, thighs, hamstrings, knees, calves, ankles, and, especially, feet.” Nothing different fifteen years later!)

At last I reached the trailhead, and stopped to sign out in the register. (I noticed the three sportsmen had been too cool for that precaution—or courtesy, you might say. To save others worry and trouble.)

4/9/14Bubba9:10

4:45

Tough going, fair bit of snow.

But got ‘er done.

That’s the way Bubba would say it.

My motorcycle waited alone in the parking lot, I was glad to see, with the shadows growing long. Earlier, when I was setting out, a late-model SUV had been parked there, its sides dusty and badly scraped by branches (probably a rental, to be abused so recklessly!), and one campsite had been occupied with a tent and four-wheeler. That may have accounted for the three hikers I encountered, coming down so early, but the place was deserted now. The nearest people were at the Wildrose Campground far below, so if anything nasty had happened, it would have been at least a day before someone noticed my abandoned motorcycle and finally came looking for me. Almost certainly too late, in that extreme exposure.

I struggled out of my hiking boots and back into my riding gear, the effort of bending over and getting boots on and off enough to set me groaning and grumbling. Swinging a leg over the saddle (ouch!), and standing on the pegs for the first rough descent was also a strain for my weary legs. I was glad to get back to pavement, settle back and just cruise the rest of the way to Stovepipe Wells.

I was thinking along predictable lines. There will be whisky. There will be a hot shower. There will be steak. There will be red wine. There will be sleep—early and long.

So let it be written; so let it be done.

Before sunrise I was up and quietly packing the bike, aiming to ride out through the other “classic” point of entry, Townes Pass. So many stories attach themselves like flags to places all over Death Valley for me—even that pass. One shining memory is riding in that way for the first time, in autumn, 1996, with Brutus—earlier pausing at Father Crowley Overlook above Panamint Valley as the moon rose, then over Townes Pass and into Death Valley, seeing the place for the first time like that.

Another story tells of a Chicago businessman named Albert Johnson who visited early in the 20th century, and found relief for his health in the arid heat. In the 1920s, he and his wife Bessie constructed a massive Mission-style mansion in Grapevine Canyon. He employed a character named Death Valley Scotty to look after the place (it soon came to be known locally as Scotty’s Castle, which suggests a tale or two), and the story spins out from there. In 1943, Albert Johnson’s wife Bessie was killed in a car accident in Townes Pass.

My entire journey to Death Valley this time had become a pilgrimage of sorts, not only to Telescope Peak, but to the place itself. Even choosing to ride in through Death Valley Junction to Dante’s View, rather than the equally scenic Salsberry Pass route out of Shoshone and past Badwater, had been deliberate—to make this visit emblematic. Not just memorable, but a summary of all of my memories of the place, and a symbol of what I hoped I could share with others.

Because magic.