photo by Kevin J. Anderson

One morning in February 2015 I received a call from an old friend, Rob Wallis. For close to twenty years, with his longtime partner Paul Siegel at Hudson Music, we had collaborated on a series of drumming DVDs. Just a few weeks before Rob had been in Southern California, and we had got together with a couple of other East Coasters who were also in town for the annual musical instrument-makers’ show, NAMM.

Like many good friends who have many good friends, Rob and I are not in frequent contact, maybe once or twice a year. But to add to the truly paranormal aspect of these events, Rob had just been out shoveling snow around his house. He thought of my affection for winter and snowsports, and snapped a selfie to send to me.

photo by Rob Wallis

When Rob went indoors, he picked up a mysterious voicemail. An elderly lady said she was calling from Colorado Springs, then launched into a story about her husband having found a duffel bag years ago, then forgot about it in their garage. Recently she was clearing out the garage, and found the bag again. She said there were papers in it with my name on them “dating back to 2004,” “a very nice watch,” and, somehow, Rob’s telephone number.

As Rob recounted these facts to me, he sounded hesitant and mystified—it made no sense to him. I knew right away what it had to be—though my brain was reeling at even the possibility.

It had been eleven years ago.

Photo by Brian Catterson

As we set the Wayback Machine for June, 2004—a time when I cared much less about photographic records—we may pause along the way in June, 2008. This day was a fine example of the typical conditions for that season in the high elevations of Western Colorado, and featured the same cast of characters.

In 2004 I had been riding through that same area with my American riding partner Michael and frequent guest rider Brian Catterson (every tour since Vapor Trails in 2002). Brian’s rides with us always seem to be accompanied by thunderstorms, torrential rain, blinding fog, and even sudden blizzards. The summer of 2004 was no exception, as Brian joined us for two days off between a show in Houston and one at Red Rocks in Denver. It was Rush’s Thirtieth Anniversary Tour, R30, and as we travel back to that time, I have a handy “vehicle” for the journey. The events in question were carefully documented for the book I wrote about that tour, Roadshow: Landscape With Drums, A Concert Tour by Motorcycle.

We pick up the action in Colorado, on June 28, 2004. The previous day Michael, Brian, and I had ridden up through New Mexico’s fine backroads to Taos for the night (with thunderstorms), and that day across Colorado (with roadside snow, rainshowers, and even thick flurries at the summits).

Nearing Denver in early afternoon, I waved to Michael and Brian and split off where highways 24 and 285 divided. I was heading east to spend the night with Kevin Anderson and his wife Rebecca near Colorado Springs, while Michael and Brian rolled on to Denver to visit Brian’s brother.

photo by Brian Catterson

[blurry focus time-shift to June 2004 — from Roadshow. . . ]

. . . the dark clouds finally began to release their showers, so I settled into a more relaxed pace. As the road descended, I just stayed with the flow of traffic, taking it easy on the wet road. I began to encounter lines of vehicles backed up at traffic lights, and at one of them, just after Manitou Springs, a small pickup pulled up beside me. A bearded man in a park ranger’s uniform leaned over and called through his passenger window, “You dropped one of your boxes back there.”

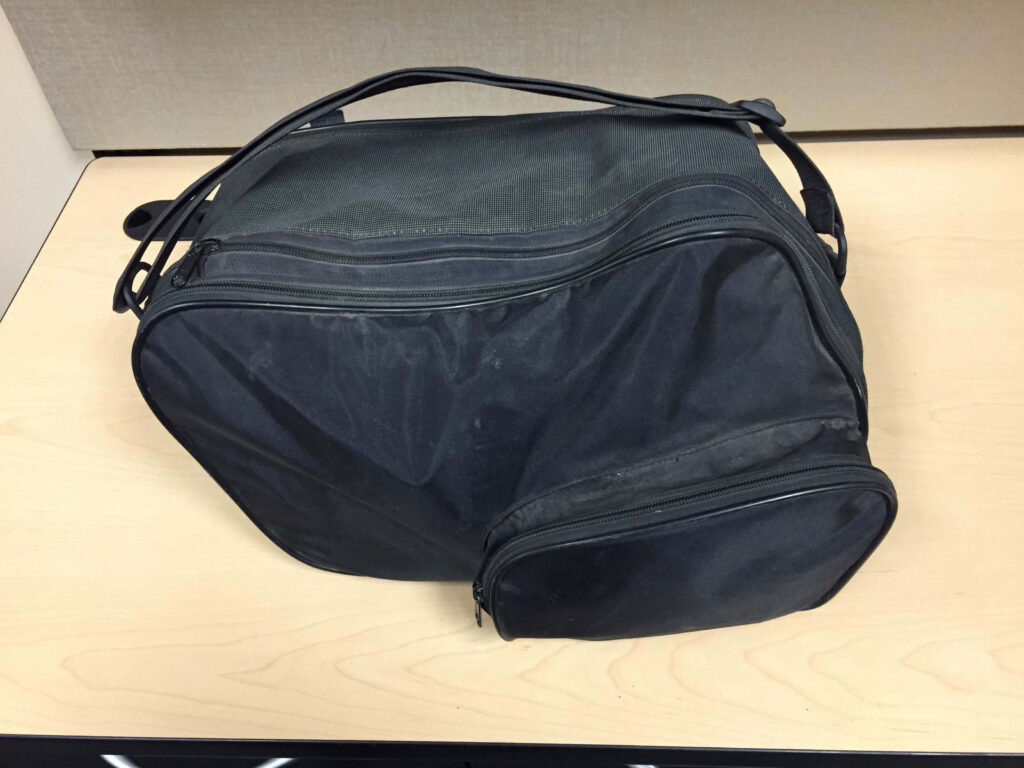

I automatically looked to the rear of the bike, saw that my right-side luggage case was gone and felt an immediate chill of alarm and fear. The hardshell cases were locked onto the frame of the bike, so one of them coming off was like, say, losing the trunk of your car.

“About a half mile or a mile back,” the ranger said.

Thanking him, I made a U-turn at the lights and raced back up the divided highway a mile or so, then turned around and rode back in the drizzling rain, slowly scanning the roadside. At first I hadn’t been too upset, thinking I would surely find the case lying beside the road and everything would be okay, but I didn’t see it.

Still hopeful, I thought, “Maybe I didn’t go back far enough.”

I turned around again, sped uphill a couple of miles this time, then circled back and rode slowly over that same stretch of road, desperately scanning for that luggage case. It wasn’t there.

I tried again, riding back a little farther this time, but there was no sign of it.

I started to get upset, going over in my head all that was in that case. Some of it was replaceable, of course: a few clothes, the “little black book” of our itinerary, a spare faceshield for my helmet, tire repair kit, some maps, Swiss Army alarm clock, Cycle World baseball hat, and the venerable plastic flask half full of The Macallan. (Precious, but replaceable.)

Then I began to add up the irreplaceable items, like my shaving kit and medicines, my phone and address book, a copy of Traveling Music with all of my proofreading notes in it, the little Zeiss birdwatching binoculars Jackie had bought for our East African safari in 1987, and—worst of all—the Patek Philippe watch Carrie had bought me for my fiftieth birthday and the Cartier engagement ring she’d given me in 2000. I didn’t wear them when I was riding or drumming, but I liked to have them with me, in what ought to have been a safely locked case.

Where was it?

One corner of my mind knew this wasn’t the worst that could happen—my imagination always allowed for the possibility of extreme, fatal disasters. But at the same time, having barely survived some tragedies that weren’t imaginary had left me permanently fragile. I lived and functioned inside a thin armor of “adaptation” that was easily pierced, and I was feeling bad about this lost case, near tears. I stopped at the side of the road, lit a cigarette with shaking hands, and tried to think what to do.

Nothing I could do, really, except hope. Perhaps some Good Samaritan had picked it up, a fellow motorcyclist tossing it into his van or pickup. As a Canadian, I naturally hoped it hadn’t inconvenienced anyone, but maybe the fallen case had landed in the road, blocking traffic, and a cop had picked it up.

photo by Brian Catterson

From the time the case fell off (caused by the failure of a five-dollar bolt, it turned out) until the ranger told me about it and I raced back there, not more than ten or fifteen minutes could have passed. [Later I learned I wasn’t the only new BMW GS owner that dropped a luggage case, either—I shoulda sued ’em.] But I would still hope for the best. It was the way I was made.

At least I still had the directions to Kevin and Rebecca’s house in the map-case on my tankbag. It was getting late in the afternoon, and still raining. I decided to carry on, get to their house, then try to deal with the situation. Following the directions onto I-25 and north in the chilly drizzle, I climbed again from 6000 feet at Colorado Springs to 7000 feet at Monument, before getting lost in a maze of tree-lined roads in the rainy twilight.

Some of the street names made sense, but something seemed to be missing—I couldn’t find their street. Worse, I didn’t have my phone book, so I couldn’t even call them. I headed back toward the interstate and stopped at a little strip mall. A dentist’s office was just closing, and the nurse gave me the missing piece of information. When I had copied down Kevin’s directions from his email, I had missed one line, one street name where I was supposed to turn.

After all that, and 734 kilometers (458 miles) of mountain riding, I was tired, cold, wet, and feeling low. When I pulled up in front of their house, I tried to pull myself together and prepare to be sociable. Kevin walked out into the driveway to meet me and I began blabbering about what had happened.

[I think first I asked if he had any whisky.]

Photo by Rebecca Moesta

[Blurry time-shift again—to four or five days later, up in Washington state, still from Roadshow . . . ]

When the bikes were parked outside our adjoining rooms at the M&M Motel in Connell, Michael and I performed the Macallan ritual, then split up to have our showers and quiet time. Turning on my cellphone to check for messages, I paused to listen to one from my brother Danny. He wanted to make arrangements for him and his family to meet us the next afternoon. I made a mental note to call him, erased the message, and listened to the next one.

It was a man’s voice I didn’t recognize, and after he gave his name, he went on to say he had picked up my luggage case. It was “all intact,” and he had drilled it open and found my phone book, with my cellphone number inside. When I realized what I was hearing, my mind went electric, and I thought, “Omigod—I’ve got to play this for Michael!”

He had been skeptical about my earlier optimism, and indeed, by that point I had resigned myself to the loss. Now I couldn’t wait to show Michael there were good people in the world. My finger went down to save that precious message, but out of habit, shock, and fatigue (“fatigue makes you stupid”), I realized—even as my mind screamed, “No-o-o!”—I was pressing the “Delete” button.

My head dropped, and I stared at the phone and my traitorous finger in disbelief.

Even then, I didn’t think it would be a big problem. Surely we could trace the number of that incoming call. Or the Good Samaritan might call back; he had sounded like a good guy.

I went next door to Michael’s room and told him what had happened. He looked at me, shaking his head, and I snapped, “Shut up, man—he’ll call back!”

You would think so, but so far, Michael had been getting nowhere with the phone company and we had decided to be proactive. After a local investigator had failed to turn up any clues, or any witnesses, Michael arranged to place a good-sized ad in the Colorado Springs newspaper. We offered a “substantial reward” for the return of the luggage case, and gave Michael’s 800 number. We ran it for a few weeks, but no response.

In Michael’s case-hardened (ha ha) view of humanity, he figured the guy would eventually find the valuable watch (in a zippered side compartment of my shaving kit), and change his mind, deciding, “Oh well, he didn’t call back—it’s mine.” But I still had faith—or at least hope.

photo by Carrie Nuttall

[blurry focus time-shift back to the present day]

The years went by—a decade went by—and the lost case slipped from memory. But as I talked on the phone from my office in sunny Los Angeles to Rob in snowy New York on Tuesday, February 4, 2015, all of that flooded back. But from so long ago, I could hardly absorb it.

How many times in the past ten years had readers of Roadshow asked me if I ever got that case back? I’d always had to give a rueful shake of my head and say, “Unfortunately, no.”

And now—presto change-o!—that luggage case and its contents were back in my life. Imagine losing a suitcase or a cardboard box full of close personal possessions for over ten years. At first the vanished items would be achingly real and personal, and their loss would hurt. With the passing of years, the objects cease to be “attached”—or you cease to be attached to them—and they are all replaced in your life by new versions. Like one of those time travel stories where a person or object can’t appear twice in the same place—these are a phantom shaving kit, gold watch, binoculars, ring, and so on.

One thing I changed right after that loss was to replace the BMW luggage cases with aluminum Jesse cases that couldn’t fall off—their ads showed the bike being lifted by the luggage mounts. I was never able to trust the BMW cases again.

Tupper Lake, NY

Right after I got off the phone with Rob, I had to call Michael. He would not believe it either. I also decided to enlist his help in getting it back—I simply felt so overwhelmed by this news that I wasn’t ready to face it directly yet. As the saying goes, I “couldn’t deal.”

Fortunately Michael and I were friends with a police officer in a neighboring Colorado town. Because his duties are sometimes of a sensitive nature, we’ll call him Leo, for “law enforcement officer.” (In fine dramatic irony, Michael got to know Leo at around that same time, 2004, during a local investigation into a psycho-stalker who was threatening violence against me. From the three of us dealing with the worst side of humanity, homicidal mania, now we were dealing with the best side, simple goodness.)

I asked Michael to call the lady, and when he suggested to her that we would send someone around to pick up the bag, she became audibly nervous.

“Oh—I don’t know . . . who . . . who are you going to send?”

When Michael explained it would be a uniformed police officer, she seemed comforted. I also requested that we arrange for Leo to give her the “substantial reward” our newspaper ads had promised eleven years before. And I insisted, “Don’t take no for an answer.”

Leo met the lady, Carole, and her husband, Rusty, in a park on a blizzardy February day. He had learned they lived in a nearby trailer park. Carole did most of the talking, and Leo got the feeling she was “genuine and good”—“there was a sweetness to her.”

They were both in their seventies, weathered with hard living, and had only been married a few years. Rusty was a lifelong tradesman, with toughened hands and layers of paint-spattered clothes. Beside his mobile home he kept a couple of sheds full of tools and equipment, and he had stored my bag there until it was covered up and forgotten.

Photo by Leo

It turned out Carole had taken the lead in contacting me because as the “new broom” in his life, she had urged Rusty to tidy things up. In turn, when the long-lost bag appeared, he asked her to find its owner.

When Leo handed him the envelope, Rusty did not open it. Leo said. “The only time he really spoke was to tell me how impressed he was with the way the bag was packed and that he knew the guy that owned it rode motorcycles and was a serious traveler. Carole never asked who the watch belonged to but thought it had to be important to the owner to cause so many people to call her. I thanked them and they walked back to the trailer park together.”

I was glad Leo gave them a thousand dollars—it would mean something to people in those circumstances. A day or two later Michael played me a voice message from Carole saying how they hadn’t expected anything as a reward, and were very delighted by “the dollar amount.”

Once Leo had sent the bag back to me, I had to decide what to do about it—all the stuff in it.

For example, of the two identical Patek Philippe watches, which one would I keep? I would sell one to pay back the insurance company (yes, I know—it’s like a twist on a humorous turn of phrase I see lately:

“‘Let’s give the insurance company back their money’—said no one ever.”

But Bubba and the Professor agree it’s the right thing to do.)

So I have to choose between the sentimental value of the first watch and the much longer-term possession of the second—less than two years versus ten years. I think experience and well-earned patina trump history this time. Besides, the older one had been sitting in a garage all that time in the extreme weather of high-elevation Colorado, alternately baked and frozen solid. It’s going to need some work. I did wind and set it, and it worked overnight, but the oil must need replacing, at least. And the leather strap too, likely—it carries a terrible stench that affected everything in the bag. Under those same temperature extremes, it seems the Macallan degraded into a corrosive liquid that ate through the cap and leaked away. The result was a foul, pervasive reek, pungent and faintly nauseating.)

As I started to put the story’s details into words, I went back to Leo and asked for his impressions and more details of how all this happened! Leo reported back:

“I asked Rusty how he found your belongings. Roughly eleven years ago, Rusty was driving his pickup truck along Ridge Road and the 24 Bypass. Back then it was just known as Highway 24. He remembered seeing what appeared to be a plastic trunk/ suitcase lying in the middle of the road. Rusty collected this item and put it in the back of his truck. When he returned home, he drilled open the case to discover a black bag. It was at this time that Rusty felt he should not open the bag. He did not know why, but just had some sort of feeling that he should not search the bag. Rusty felt that he should try to get it back to the owner and conducted a very quick search for identifying information. He said he remembered seeing a tool kit for repairing tires, a watch, and an address book. Rusty was adamant to explain that he knew that the owner of this bag was a serious motorcycle rider and traveler. When he talked about this, it brought life to the conversation —he said that the person who packed this bag was a professional and really knew what he was doing. I asked him why and Rusty further explained that the way the clothes were rolled, the types of tools, the maps, flashlights, and how these items were packed all pointed towards a very experienced rider. Rusty left a message for someone to contact him, but did not hear back. He went to the garage and stored the bag on a shelf. Well, over the years many more items were placed in this garage and it became buried in handyman equipment, industrial saws, parts, personal items etc . . . Due to the nature of his work and the fact that the bag was buried, he just forgot about it.”

Leo said he asked Rusty why he hadn’t searched the bag, taken the watch, or sold the items, and Rusty said, “There was something about this bag that I just didn’t feel right about doing that.” Leo reported his impressions, “He can’t explain if it was divine intervention, goodwill, or a combination of the two, just that something told him to get it back to the owner.”

Learning this background made me even more impressed by the simple benevolence of this man, and now the “sweet, genuine, and good” lady making that one move—picking up the phone to make a costly call to the other side of the country, only guided by a clue. Leo reported Carole had first tried a few numbers from my phone book that were no longer in service. How did she end up reaching Rob Wallis, at the alphabetical end? And what are the odds of Rob having the same phone number all those years later?

(Plus now I see that back in 2004 Rusty must have found my cell number, still the same, printed in the back of my book. I had printed it under “Personal Information,” with this unmistakable notice in blue ink: “NEP—For reward call —.”)

Anyway, somehow, it all worked out. Eventually . . .

It just took a little longer—a little longer than ten years.

After talking to Michael, I wrote next to Kevin Anderson to tell him this amazing and completely unexpected resolution to the story. Addressing Kevin as the prolific author of wildly fantastic tales, I wrote under the title, “You think you can invent a tale of unbelievable miracles?”

Naturally, Kevin remembered the incident well, and was equally astonished.

I’m not sure if the pope would declare this a proper “miracle,” with no lives saved by the magical intervention of invisible friends (new definition of religious squabbles: “My invisible friend can beat up your invisible friend”), but come on—what else would you call it?

In this crazy mixed-up world, all I know is, it’s some kind of a story—with a bittersweet ending and renewed faith in humanity. A small dark blot in my past, with its fading nebula of pain and regret, has suddenly flared into a bright star of relief and gratitude.

You can’t make that stuff up.

photo by Leo