Eleven miles off the coast of Southern California, Anacapa is one of eight Channel Islands. It is the only one whose name is not Spanish, but comes from a native Chumash word meaning “mirage.” The first Europeans arrived in 1542, led by Juan Cabrillo, and like so many seekers in that Age of Exploration, Cabrillo was dreaming of something else entirely—a mirage of his own. He did not set out to “discover” California or its Channel Islands; he was searching for a route to China, perhaps the mythical Strait of Aniàn, or the Northwest Passage. Leading his three ships north along the Pacific coast from present-day El Salvador (The Savior), he claimed and named everything he saw for the Spanish crown.

When choosing names for newly-encountered land features, a typical practice by many French, Spanish, and Portuguese explorers was to look up the saint whose day the Catholic church said it was, and give it that name. Thus we have the St. Lawrence River, San Juan, São Tomé, and so on. In the same fashion, British explorers gave us Christmas Island and Easter Island. (Canadians like to joke about John Cabot sailing in 1497 under the British flag to what would be the East Coast of Canada—seeking another mirage, a mythical island called Hy-Brazil. We figure that when Cabot sighted a certain weathered Rock, he must have smote his breastplate and bellowed theatrically, “What shall I call—this new-found land?”)

For thousands of years, the Chumash and their coastal neighbors the Tongva were part of a thriving, sophisticated culture. Hunters, gatherers, and artisans traded along the Pacific coast, out to the Channel Islands, and inland among the Mojave and Shoshone. After Cabrillo’s visit, they would live on unmolested for another 200 years, save for occasional visits by whalers and seal-hunters. They could not know it was only a “grace period”—before more explorers, missionaries, soldiers, and settlers began to arrive, and, one way or another, destroy them. By that time, all the placenames Cabrillo dreamed up were forgotten and later renamed, but the principle remained: the other Channel Islands are Santa Catalina, San Clemente, San Nicolas, Santa Rosa, Santa Barbara, San Miguel, and Santa Cruz. The last four make up Channel Islands National Park, along with Anacapa.

Compared to some spurious saint’s name, this explorer finds Anacapa to be more evocative and attractive—in the true sense of that word: magnetic. Just to contemplate the Chumash people, thousands of years ago, having a word for “mirage”—that mystical abstraction forges a deeper connection across time than knowing their word for water or fish. They had illusions and imaginings, too, as well as words for them, and were likely more like us than we might imagine.

However, despite the lure of its name, Anacapa was not the first of the Channel Islands I would visit, or even the first I heard of—each of them took shape on my mental horizon over a lifetime, indistinctly, like a mirage.

The first connection is a childhood memory of a song called “26 Miles (Santa Catalina),” a hit for the Four Preps in 1958, the summer before I turned six. In our suburban split-level in Southern Ontario, or in our family Buick, my father always had the radio on, and I heard that song many times that year. The chorus echoes readily in memory, with its lilting shuffle.

Twenty-six miles across the sea

Santa Catalina is a-waitin’ for me

Santa Catalina, the island of romance (romance, romance, romance)

The following clever verse would not have registered on a five-year-old’s consciousness, or sense of humor, the way it does now.

Twenty-six miles, so near yet far

I’d swim with just some water-wings and my guitar

I could leave the wings—but I’ll need the guitar

For romance (romance, romance, romance)

It is one of the first pop songs I remember—though I notice the year did offer some other enduring hits: “Tequila” by the Champs (go Peewee Herman!), “All I Have To Do Is Dream” by the Everly Brothers (the version by Bobby Darin and Petula Clark is lovely, too), “The Purple People Eater” by Sheb Wooley (well, maybe that one hasn’t endured so well, but at least it’s weird!), “To Know Him Is To Love Him,” by the Teddy Bears (Phil Spector’s first hit, said to have been inspired by his father’s epitaph), and a couple of doowop classics, “At the Hop” and “Get a Job” (source of Sha Na Na’s name, a recent crossword clue reminded me—and I can never forget when Rush opened for Sha Na Na at a school in Baltimore on my twenty-second birthday, Sept. 12, 1974).

Such lists always remind me that I have indeed lived in what the Chinese call “interesting times.”

Friend Craiggie and I visited Santa Cruz Island in 2009 (“Under the Marine Layer,” in Far and Away), almost exactly five years before our next visit to the Channel Islands—when the above photograph was taken. Our vessel of exploration this time was the powerboat in the foreground (or foresea), owned by my longtime riding partner and director of Homeland Security, Michael. He has another name for it, but I call it the SS Obtuse. (After its master.) He aspires to be a yacht-dwelling private investigator, like one from a previous generation, Frank Sinatra in Tony Rome and Lady in Cement (great title!)—both films part of what is called a “late ’sixties noir revival.” Certainly Michael would like nothing more than to be part of a noir revival, to have his imaginary life portrayed by a brooding young actor with chiseled cheekbones, as a combination of Sam Spade and Jason Bourne—gumshoe and ninja.

A girl’s gotta dream, I guess.

Mirage, mirage . . .

This may seem like gratuitous autoporn, or a sly reference to espionage fantasies, but the Channel Islands are there, I promise—just the way I first saw them. After I moved to Southern California in 2000, whenever I rode my motorcycle or drove a car on the Pacific Coast Highway north of Malibu—the wildest, prettiest stretch in Southern California—I would see their distant shadows way out to the northwest. Anacapa, Santa Cruz, and Santa Rosa, as I know them now.

Around that time Carrie and I lived in a townhouse in Santa Monica, and its roofdeck had a fantastic view to the west, out through the shoreline of fan palms to the Pacific’s distant horizon. On clear days, I liked to see the jagged spine of Catalina in sharp relief, rippling green against the sparkling blue sea and sky. Even more rarely, maybe four or five times a year, often in winter’s clearer skies, I spied a tiny dot north of Catalina. If I stretched out my arm toward it, it was the size of the tip of my thumb. It seemed to float above the ocean, like a pale mirage, and I wasn’t even sure it was real.

The vision fascinated me, and I had to know more about it, starting with finding out that it was indeed real—Santa Barbara Island, one square mile, the smallest of the Channel Islands, and almost forty miles offshore. In the way things or places become symbols and tug at you (or at least at me), I wanted to go there. Every time I looked at a map of the California coast, my eyes went to that dot in the blue part. On those rare super-clear days when I saw that thumb-tip so far out in the Pacific, a primitive, magnetic urge was triggered: “Want. Go there.”

Santa Barbara Island was open to the public, as part of the national park, but not easy to visit. At that time the National Park Service concessionaires only offered two boat trips a year, stretching over summer weekends, so getting to Santa Barbara Island would require long-range plans, and a well-organized camping expedition.

Photo by Christian Stankee

In April 2009, Greg Russell (Master of All Things Creative) hiked with me to the top of Sandstone Peak, the highest in the Santa Monica Mountains (though only around 3,000 feet). From there we looked west over the northern Channel Islands, and again they spoke of remoteness and mystery. And suddenly, science. (Natural science, mind you, not the dizzying theoretical stuff. But what a marvelous title: And Suddenly, Science.)

I had learned that despite its name, Sandstone Peak was an ancient volcano (entirely lacking in sandstone, strangely), and was part of a chain that continued out under the Pacific and formed those islands. My desire to get closer to them was becoming a tractor beam on my imagination, and finally grew strong enough to force the issue. Just a month later, Craiggie and I caught the Island Packers ferry from Ventura to Santa Cruz Island. The entire experience was the stuff of boyhood adventure, pausing along the way to watch a massive pod of dolphins perform an elaborate water ballet all around the motionless boat, seeing the forbidding shores of the islands materialize out of shifting curtains of mist and fog, then landing at Prisoners Harbor.

(I noted in “Under the Marine Layer” how the place names on Santa Cruz Island are right out of a Hardy Boys or Tintin adventure—Scorpion Ranch, Smugglers Cove, Chinese Cove, Black Point, Painted Cave, and Prisoners Harbor. That last name evokes a story, but its details are lost in the mirages of history. The bare bones are that during the Spanish era a number of convicts were marooned on the island, with water and provisions, and later they disappeared—either died off or rafted to the mainland, no one knows.)

Craiggie and I spent a few hours hiking (and lunching) in the island’s entrancing isolation (that word derives from the Latin insula, island), and decided we wanted to visit more of the Channel Islands. My map of California had suddenly become much bigger.

However, years went by when we pursued other adventures, though I still often thought of the Channel Islands—especially longing to visit little Santa Barbara Island, that occasional thumb-tip on the winter horizon. When our “Tony Rome” acquired the SS Obtuse last year, wheels started to turn in my head. I suggested that Craiggie and I charter Michael’s boat for a visit to famed Catalina (like Vegas, it’s always just Catalina, to insiders and hipsters, like all of us want to be), with a side expedition to Santa Barbara Island.

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

Our crossing was unusually rough, eight-to-ten-foot seas and a fierce wind tearing spindrift off the crests. Sheets of spray whipped high over us, lashing down across the deck and canvas top. All that kinetic energy was throwing the boat and its crew around some, of course, bucking and yawing, while the dinghy leaped and tossed in our churning wake. Later Michael said it was the heaviest weather he had experienced in at least a dozen crossings. We learned that just after we left the mainland harbor the Coast Guard had put up the red “small craft warning” flags. On the shortwave radio we heard a call to Vessel Assist (the nautical equivalent of the Auto Club) to come to the aid of a capsized sailboat. Michael and I had both done quite a lot of blue-water voyaging before, mainly under sail, him around the Hawaiian Islands and me in the Caribbean and New England, so we were used to a bit of weather, and weren’t unduly concerned. (Though we did sing a few choruses of the Gilligan’s Island theme song, including “The weather started getting rough/ The tiny ship was tossed/ If not for the courage of the fearless crew/ The Obtuse would be lost.”)

From when I first knew Craiggie as a teenager working at record stores in Southern Ontario, to forty years later in the music legals department at Fox Studios and living in South Pasadena, his life has sometimes spanned unbelievable tangents. He will start recounting some episode from when he was a barroom rocker, an actor in TV commercials, or a dirt-track racer, and I have to raise a hand and say, “Oh come on—you’re making that up!” However, his experiences had not included riding in a smallish boat in a rough sea, and he was feeling a little “unsettled.” With a nod toward Craiggie, Michael said to me, “You can always tell when they go quiet.” Craiggie sat still in a corner, silent and a little gray looking. We gave him the salty old advice about keeping his eyes on the horizon, and told stories about other people we’d sailed with being seasick, and about times when we had been afflicted with the mal-de-mer ourselves. (For me, just once on an overnight sail on the schooner Orianda in the stormy Atlantic between Nantucket and Newport. I was fine on deck, until I tried to go below and sleep. That didn’t work.)

When we finally motored into the lee of Catalina, and the waves calmed a little, I looked around at everybody and said, “At least nobody barfed.” Craggie raised his head with a grim face and held his thumb and forefinger an inch apart, as if to say, “This close.”

Even in Avalon Harbor the wind was strong, driving hard against the boat’s sides, and Michael had an awful time trying to steer onto the mooring. The Harbor Patrol craft, like a small tugboat, took our stern line and helped guide us in, while I crouched in the bow to grab the upright pole on the mooring ball. The harbor master told us we were the only boat to come in from the mainland that day—in fact, all the ferries and tourboats into and out of Avalon were canceled, and even a massive cruise ship had changed course and anchored in Baja’s Ensenada instead. So it was some weather, all right.

We spent two nights ashore in a pleasant little hotel on the waterfront, enjoying the above view with our evening cocktails. I was pleased to discover that Catalina was more than I could have imagined—more and better. The port of Avalon was smaller than I had pictured—the entire island had just 4,000 permanent residents, mostly in Avalon—and that is always a nice surprise. I might say that Catalina’s closest analog in North America would be Key West, but that little island has 25,000 residents. Big difference. (But then, you can get to Key West by car.)

Approaching by sea, Avalon Bay had a quaint Mediterranean look, a curved shoreline of green dotted with scattered buildings in light colors rising in pleasantly irregular ranks. The northern point was a massive round structure called the Casino. (There was never any gambling there, but the name is said to come from the Italian word meaning “gathering place.”) The Avalon Casino, built in 1929, is a fantastic blend of Mission and Art Deco styles, and this observer admires both of those very much. One floor has the very first theater purpose-built for “talkies,” while above it is a vast circular dancehall that was famous in the big-band era—my father used to listen to radio broadcasts from the Avalon Casino in the 1940s, from our family dairy farm in Southern Ontario.

The narrow, picturesque streets in town were filled with electric golf carts of every description, parked and moving, but very few cars. Craiggie, Michael, and I visited some of the fine bars and restaurants, and especially enjoyed a perfect breakfast place called “The Original Jack’s Country Kitchen.” It truly was a scene from fifty years ago.

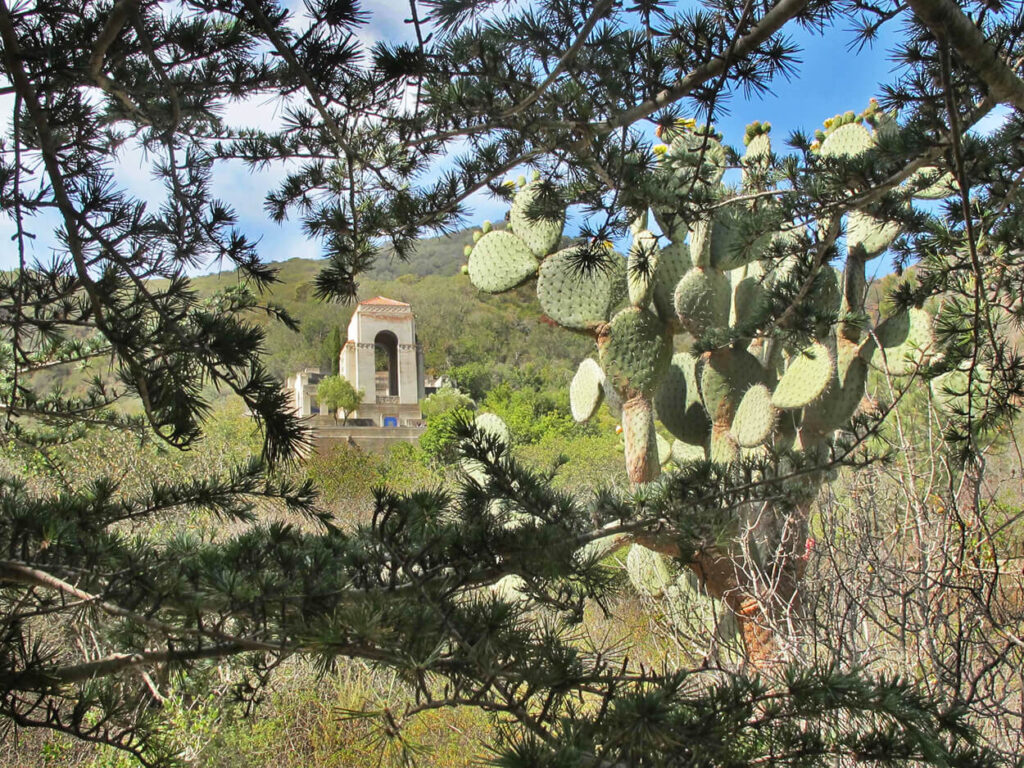

In the morning I took a hike up through the botanical gardens, wandering among many species endemic to the Channel Islands (one reason why they are called the Galápagos of North America, with at least 145 such unique plants and animals), as well as dry-climate plants from other parts of the world. Above the gardens, at the head of a chaparral canyon with a distant view of the ocean, stood a massive stone monument to William Wrigley Jr., of chewing gum fame. He bought a controlling interest in Catalina in 1919, and it was held in the Wrigley family until 1975, when ninety percent of its land was deeded to the Catalina Island Conservancy. The Wrigleys also owned the Chicago Cubs, who held their spring training in Avalon for over thirty seasons (a rare bit of sports trivia from Bubba).

The cruise ship that had avoided Catalina’s weather the previous day showed up that morning and anchored offshore. As the launches disgorged the ship’s passengers at the town dock, suddenly nearly 2,000 people were added to Avalon’s population. (A blessing for the locals, no doubt, but an intrusion on other visitors.) In the afternoon, the three of us escaped from all that by taking a Jeep tour inland, into the fenced-off Conservancy lands. Our driver and guide, Beth, steered us through the gates and into the backcountry, over rough tracks that truly needed high-clearance four-wheel-drive. Beth was about my age—a likewise-youthful sixtyish!—and had spent most of her life on Catalina. She told us many great stories about its history—and her own. Pointing to a tall communications tower on the island’s summit, she said, “After high-school graduation we climbed to the top of that. Probably a dumb thing to do.” (Suiting the modern response, “Ya think?”)

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

Almost immediately, we had what I would later tell Beth was my favorite moment, spotting one of the rare island foxes sitting by a roadside bench. It was tiny, the size of a housecat, evolved that way over tens of thousands of years into a species unique to the six larger Channel Islands—each of which has a separate sub-species (again, the Galápagos comparison applies). Beth pointed out its radio collar, and suggested that someone had probably been feeding it around there. The island foxes have only barely survived into this century, with great efforts from natural scientists and the park service. Whether or not one cares about a remnant population of dwarfish canines, their story is one of many complex environmental histories that unfolded on those islands—and perhaps it is emblematic of an entire rearguard struggle at which some might cheer, and others might jeer.

From the era of Spanish settlement, the vast ranchos, in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and well into modern American times, the islands were overrun and devastated by cattle, sheep, and pigs. Other human-introduced invaders were rabbits, rats, and even housecats, plus many species of plants—range grasses for the animals, and groundcover to fight the erosion caused by overgrazing. Right there we see one vicious spiral—overgrazing, erosion, invasive species—and by the twentieth century, there were several such destructive patterns attacking the islands’ natural diversity.

The foxes’ troubles began with a bug-killer—DDT, a pesticide used widely in the 1960s until scientists finally proved (in a preview of modern times, against the resistance of lawmakers and corporations with vested interests) that the poison made its way through the food chain and weakened the eggshells of larger birds. Many birds of prey were affected, especially those who fed on fish, threatening the swift annihilation of ospreys, pelicans, hawks, and bald eagles. Unlike climate change, this was not gradual, but immediate—numbers were plunging radically every year. With so much agriculture in California, and flood, waste, and irrigation water running straight into the Pacific, the bald eagles that had long nested on the Channel Islands fed on fish contaminated by the runoff, and their nests began to fail. Within just a few years, the bald eagles disappeared from the islands, and larger golden eagles moved in from the onshore mountains. They didn’t eat fish, but one of their favorite foods was . . . foxes.

To remedy that imbalance, apart from banning DDT, it was necessary to reintroduce bald eagles to the islands, remove the golden eagles to the mainland, their “natural” habitat, and build the dwindling fox populations by captive breeding. Amazingly, all that was done, and now the foxes have a healthy population on each of their six island homes. One small miracle—or one little victory—in these times.

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

Another mirage that surrounds these islands—as it does anywhere on earth, really—is human history. Not just the obvious haziness of times and locales beyond one’s experience, but something that only those who take the trouble to learn about a place can even sense—an aura of ghosts. When you have read about a certain setting where things happened, then visit it, finally you lay eyes upon a natural stage where human dramas have played out. “Long ago and far away” is an immediate trigger for the “story impulse” in many of us, not unlike “once upon a time,” but with a sense of place as well.

For example, as a boy I was intrigued by the exotic settings in Ian Fleming’s James Bond books—picturing, say, Switzerland, Hong Kong, or Jamaica with fascination and yearning. Later in life, when I had actually visited those places, I noticed that reading about them in more modern thrillers, like the Jason Bourne books (say, those JB initials cannot be a coincidence), I could picture the backgrounds too clearly, and they had lost their mystery—their romance.

And there we stumble across another mirage—imagination. Many travelers have carried their own illusions to some storied destination and felt betrayed, by a place that proved to be too “real” to live up to their own fantasies. One example for me, coincidentally, is not far from the Channel Islands, over on the coastal mainland of Southern California—the Mission of San Juan Capistrano. As a young bird-lover I read about the swallows returning there every year, and always remembered a watercolor my great-grandfather had painted of that mission in the early twentieth century, with the swallows circling its bell-tower. When I finally visited Capistrano in the late ’80s, I found a tourist attraction of over-manicured ruins and a brand-new “replica” basilica built by the Catholic Church, jammed between strip malls and subdivisions. I wished I had never gone there.

Other places, like London, Paris, or Venice, to give high-profile examples from this traveler’s experience, often grew beyond the fantasy into something richer and deeper—a part of my own life.

Yet in that life, a far greater number of places have just exploded into my consciousness. Many times I have stood in some amazing setting and had thoughts similar to “A week ago I had never even heard of this place!” The massively surreal mud mosque in Djenné, Mali, the medieval setpiece of Rothenburg in Bavaria, or Bryce Canyon National Park in Utah were like that—first unknown, then unforgettable.

Or first unknown—then unbelievable!

It is fitting that the word mirage comes from the Latin mirare: “1) be amazed/ surprised/ bewildered at, 2) look in wonder/ awe/ admiration at.”

From that root we also get “admire” and “mirror” (humorous if you look again at those definitions—nailing two common human polarities in our reactions to mirrors: horror and delight).

Oxford’s definition of the figurative sense of mirage is telling, too: “Something that appears real or possible but is not in fact so.”

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

Then there are sights that are real, but don’t appear possible—like this bison, one of the 150 that live on Catalina. We saw a good percentage of them on our tour, and like so many stories that drift to us through the fog of even the recent past, their history is hazy. One version tells that fourteen bison were brought to the island in 1924 for a silent film of a Zane Grey story called The Vanishing American. (From 1925 until his death in 1939, Zane Grey had an adobe house in Avalon. It still survives, sometimes as a hotel. And just by the way, what a story Zane Grey is!) However, a Catalina journalist reported that the film The Vanishing American “does not contain any bison whatsoever and shows no terrain that even remotely resembles Catalina.”

In any case, the herd multiplied to as many as 600 big animals, chewing up the flora and bulldozing the terrain. The Conservancy determined that the island could properly sustain one quarter of that number, and at first the surplus animals were auctioned off on the mainland, or sent to an Oglala reservation in South Dakota. Beth told us that nowadays their numbers are kept down by—believe it or not—birth control! Before mating season, rangers shoot exploding vials of contraceptives into the females. I joked to Beth, “Has anyone told the pope about this? Or the Republicans?”

She laughed politely, and I added, “’Cause they’d defund it for sure.”