For once, this complicated and far-ranging story involves quite a lot of sports, and only a little news and weather. But let’s start with the music.

“The Hockey Theme” was composed in 1968 by Vancouver native Dolores Claman (who would also be recognized by Ontarians of a certain age as having written “A Place to Stand” for the Ontario pavilion at the World’s Fair in Montreal, Expo ’67). Over the next forty years, Dolores Claman’s theme became synonymous with the CBC’s “Hockey Night in Canada” broadcasts. It is considered by many to be “Canada’s second national anthem,” as nearly every Canadian can hum that melody on demand, and serious hockey fans have the ringtone.

In 2008, some complicated publishing maneuvers resulted in the CBC, Canada’s government-sponsored network, losing the rights to that music to Canada’s largest independent network, CTV.

“Foul!,” cried the congregation of devotees to “Hockey Night in Canada”—the time-honored, and widest-received Canadian broadcast.

Hockey’s place in the Canadian sensibility is hard to explain to citizens of other nations, and the effect of merely moving a TV theme song to another network is a fine example. The event caused an angry public outcry, with celebrity hockey fans like Mike Myers chiming in to criticize the CBC for letting that iconic music get away.

Meanwhile, CBC executives huffed and puffed, sternly insisting, “It’s not about the song; it’s about the game.” Eventually the CBC’s “Hockey Night in Canada” replaced Dolores Claman’s dignified theme and its stately French horns with a Celtic-rock composition chosen by popular vote.

For their part, CTV planned to use the traditional theme for hockey broadcasts on their satellite sports network, TSN. A director at TSN, Eric Neuschwander, attended the Toronto performance of Rush’s Snakes and Arrows tour, and at the climax of my drum solo, with the horn shots and big-band action, Eric thought, “Wouldn’t it be cool if Neil played like that on ‘The Hockey Theme?’” He brought the idea to Andy Curran at our office (who has since been promoted to Vice President of Hockey Operations); Andy mentioned it to our manager, Ray, who then conveyed the offer to me.

My first reaction was to laugh out loud—at the incredible irony of it all. As a kid, I was skinny, weak, non-athletic, and spectacularly bad at every sport. On skates, my little twiggy ankles folded right over, and I more-or-less shuffled along the ice, until I fell down. At least the hockey stick was a helpful crutch to lean on, because among the stronger, faster boys, I never got near the puck—unless I wanted to play goalie, a cold, lonely, and often painful fate, without helmets, masks, or pads.

For a Canadian boy in those times, it was a humiliating struggle growing up that way, and—here’s the thing—it would eventually be drumming that would make my redemption against those feelings of inadequacy, and against the bullies—the jocks and frat boys—who tormented my childhood and teenage years. And now, here I was being asked to play a drum solo that would open every NHL broadcast on TSN.

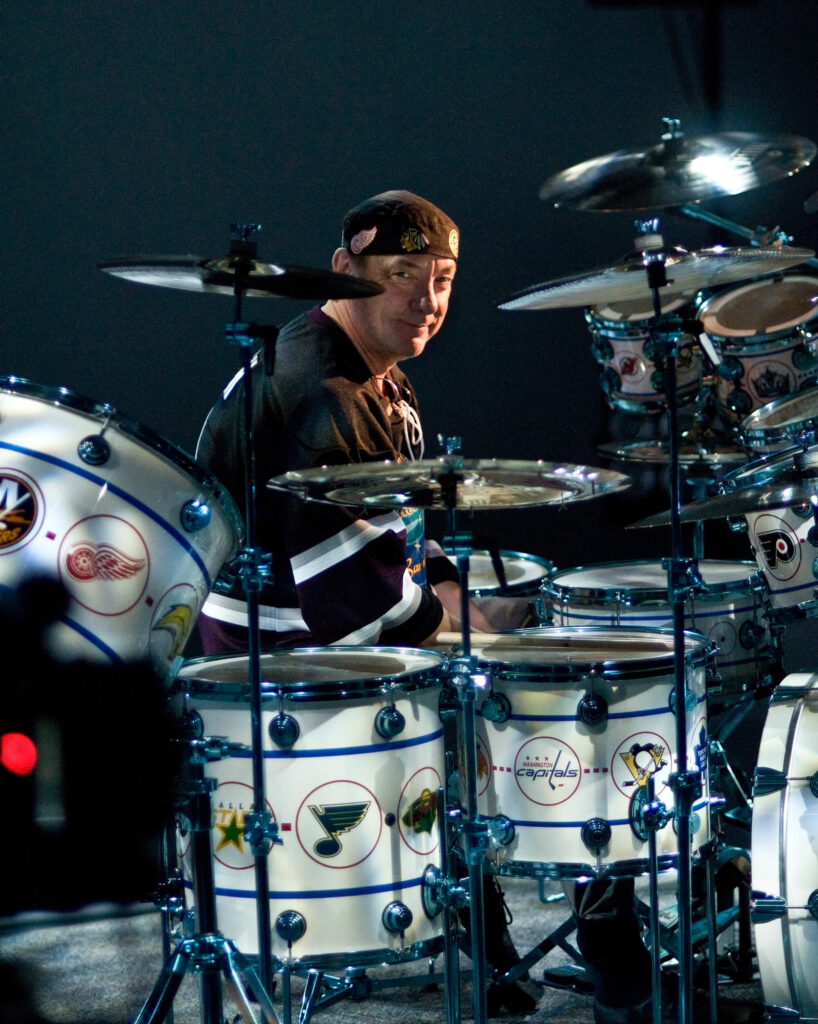

On the day of the recording and filming sessions for my version of “The Hockey Theme,” I e-mailed the following photograph to Mom and Dad—me standing behind my drums that were custom-painted with all the NHL logos, holding THE Stanley Cup, and about to record “Canada’s second national anthem.”

My caption was, “Take that, bullies from fifty years ago!”

So many unanswered questions already leap up, waving their hands frantically. What about those fancy drums? Why was the Stanley Cup there? What’s with the hat?

All will be revealed, patient reader, in the fullness of time.

Growing up in Southern Ontario in the 1950s and early ’60s, hockey pretty much dominated our lives for half the year. Backyard rinks and frozen ponds, schoolyard debates about favorite teams and players, street hockey (as portrayed wonderfully, by Mike Myers again, in Wayne’s World—“Car!,” move the nets off the street, then back out, “Game on!”), little tabletop games with rods and levers, collecting hockey cards and clothespinning them against our bicycle spokes for that “motoring” sound, watching games on black-and-white television (old Uncle John always called it “the hockey match”), my father listening to games on the radio, or the sports report after dinner every weeknight at 6:45, Rex Stimers on CKTB (that broadcast is extra clear in memory, because 7:00 was my bedtime). Rex was a classic old-time sportscaster, and his game coverage was punctuated with colorful phrases rising to an intense shout: “He winds up and shoots—a bullet-like drive!” “Ohhh—a ten-bell save!”

Dad sometimes took me to the Garden City Arena (later the Rex Stimers Arena) on Sunday nights, to watch our Junior A team, the St. Catharines Teepees (for their sponsor then, Thompson Products, the automotive parts factory across St. Paul Street West from my dad’s International Harvester dealership). The team’s name was later changed to the St. Catharines Blackhawks, when they became a farm team for the Chicago Blackhawks in the NHL, back when there were only six in the Big Leagues: Toronto, Montreal, Chicago, Detroit, Boston, and New York. (As the league expanded to today’s thirty teams, those became known as “The Original Six”—the inspiration for the hats I had made for this project, with their logos circa 1950.) With players moving up and down between St. Catharines and Chicago, and similarly with the other Junior A teams who came through, we saw many of the era’s greats, and despite being nearer to Toronto and the Maple Leafs, surrounded by fans of that team or the arch-rival Montreal Canadiens, we became Chicago fans. They were the players we “knew.”

At age eight or nine, I saw a notice in the St. Catharines Standard announcing tryouts for kids’ hockey teams. I wince with sympathy now for my deluded little self, and for my mother—who must have known better, when she drove me to the arena that Saturday morning. I shuffled out on the ice among an army of ragtag boys, and followed the coaches’ directions (I’m pretty sure the backward skating was my real downfall, metaphorically and literally).

I must have known I was hopeless; yet somehow I was not without hope—the teams would be announced the following week, and I actually ran for the paper and checked to see if I was on the list. I guess I imagined that my “secret talent” might have been recognized by a discerning coach. But no.

Another psychological awakening occasioned by hockey occurred one bitter winter day at around the same age, when my parents drove my friend Rick Caton and me to Martindale Pond, a broad expanse of ice big enough to be called a lake in many parts of the world. Rick and I had our sticks and a puck, but it was a one-sided game—Rick would just steal the puck from me and skate away effortlessly, every time. I became more and more frustrated, and was finally overwhelmed by a wave of murderous rage, the red mist. Some animal combination of envy and humiliation made me want to take my stick and swing it at Rick’s head—anything to stop him.

Lucky for both of us I had no chance of catching him, but still—the power of that violent urge, and my own revulsion at it, was an early life lesson. It was the first time I remember feeling an inner moral reflex that would return many times in my life, when I would tell myself, as I did that day, “I don’t want to be like that.”

After another thirty years of observing myself and others, and many times thinking, “I don’t want to be like that,” I addressed the subject on a Rush album called Hold Your Fire. The lyrics of the individual songs shared the theme of “instinct,” good and bad, and this one was called “Lock and Key.”

We carry a sensitive cargo

Below the waterline

Ticking like a time bomb

With a primitive design

Behind the finer feelings

This civilized veneer

The heart of a lonely hunter

Guards a dangerous frontier

The balance can sometimes fail

Strong emotions can tip the scale

. . .

I don’t want to face the killer instinct

Face it in you or me

So we keep it under lock and key

A few years after the Martindale Pond Incident, Rick Caton would be part of my young life’s redemption—drumming—as he was the lead singer in my first band, mumblin’ sumpthin’.

(The name—I know. Forty years later, I’m still having to explain it. A/ It was 1967. B/ We were fifteen years old. C/ It came from a “Li’l Abner” comic strip.)

In adult life, music took precedence over sports, but my bandmates liked to watch hockey games on motel and studio lounge televisions, for example, so I did not escape observing and even getting involved—feeling the pain of becoming emotionally invested in something you were powerless to affect—like watching “your” team struggle and fail (that would be Toronto’s Maple Leafs). Alex and Geddy had grown up in Toronto with longtime Montreal Canadiens forward Steve Shutt, and we would sometimes meet up with “Shuttie” in cities where we were both playing. (Further ironic that throughout our career, the band played in all of the NHL arenas, sharing the same “office space” as the hockey players.)

In the early ’80s, touring with another Canadian band, Max Webster, we rented small hockey arenas after shows, suited up in skates and pads, and—in the middle of the night—played outrageously inept hockey for a couple of hours. (My ankles were stronger by then, and skates were better—but I still basically shuffled around the ice. Fun, though.)

Having lived mostly in the United States for the past ten years, whenever I get to my Quebec house in winter, I like to sit in front of the fire on a snowy evening and watch a hockey game. The whole experience—the game, the players, the fans, the announcers, the commercials, the weather—is like an intravenous shot of Canadiana.

And I guess that is how my lifetime relation to hockey could be described: basically “intravenous.”

The timing for the “Hockey Theme” proposal was perfect. The band had been off that year, after three years of writing, recording, and touring, so I was eager for a new musical challenge. This one would be especially demanding, but I would have the time and energy to devote to it. And with the Blessed Event of Olivia Louise’s arrival that summer, it was great to be able to work close to home.

As recounted in my previous story, “Autumn Serenade,” I was deeply engrossed in drumming at that time, exploring styles and exercises that would feed straight into my approach to this performance. For example, the Latin feel under the beginning, and the rolling tom sections which echo my experiments in polyrhythms—firmly rooted to the downbeat, while my hi-hat foot is playing alternating upbeats. Couldn’t have done that a year ago.

So I had the time, and I had the place—Drum Channel boss Don Lombardi had been letting me use their studio when it wasn’t busy, for practicing and working on ideas, and Garrison from the neighboring Drum Workshop factory had been setting up the “practice kit” for me. (I have referred to Terry Bozzio before as Drum Channel’s “Artist-in-Residence”—now I was their “Student-in-Residence.”) Right away Don and I were excited about documenting this project, and decided to film each step as it developed and grew—bigger than we ever imagined.

The time and the place—now for the people. The foremost collaborator I needed was an arranger, and once again, earlier musical adventures came into play unexpectedly, and combined to grow into an even greater one. For the previous year’s Buddy Rich tribute concert, the bandleader had been Matt Harris (Buddy’s last keyboard player, before his passing in 1987). Matt had done a terrific job of leading the band through a long night, with seven different drummers, and had also written some arrangements for Chad Smith and Terry Bozzio that I admired. I thought he was probably the perfect man for this job—and it turned out he had been a hockey player in his youth, and had gone to a hockey camp in Southern Ontario. An experienced musician and arranger, respected music educator at Cal State Northridge, a master’s degree in music, and a smelly hockey bag in his closet. I had found my man.

Don’s crew filmed the first meeting between Matt and me, as we sat at the piano and discussed ideas for the arrangement, then played piano and drums (brushes) to explore different feels and tempos. The parameters were simple: I wanted to pay due respect to Dolores Claman’s original composition, and the equally classic orchestration, to some degree, while making it more of a “solo drums” performance.

That performance had to be one minute long, no more, so that was a limitation of its own. I was determined to get “everything I know” into that one minute, so it would be as action-packed as I could make it. Matt and I discussed having a quiet passage, for example, a Latin feel vamping away softly as a contrast to the full-out drums-and-horns sections, but soon decided, “We don’t have time for that.”

Matt would contract the musicians for the actual recording, from the cream of L.A. session players, and also offered to set up a rehearsal with his students—as he had done before the Buddy Rich concert in 2008. It would be a great experience for them, and a chance for Matt and me to iron out any problems in the final week before the Big Day—now finalized as December 7, six weeks away.

Jose Altonaga

As I started working on my drum part, Andy (Vice President of Hockey Affairs) brought me a request from Eric, the director at TSN—he wanted me to record the performance first in a recording studio, then move to a soundstage (on the same day) and reproduce it for the cameras—without microphones all over the place, and with more control of lighting and camera angles. At first I was reluctant. You can’t “lip-sync” drums, of course, as drumming is so physical that it’s not “fakable.” When you watch somebody try, and hear something completely different from what you’re seeing, it’s painfully, humorously obvious.

Ideally (freighted word), I would have preferred to record and film it live, as a matter of “purist” authenticity. But I understood the director’s wish, from a visual professional’s point of view, to make it look as good as possible. The alternative—recording in a giant soundstage where they could also film, would be a compromise acoustically. At least doing it their way would result in the best possible sound, and that was the main thing. And in any case, I always hate to seem “difficult.” Half-jokingly, I told Andy, “I can do it—because I am a professional.” In the filming of past band videos, I had simply played along to a part I knew well, so the experience was the same for me, and hopefully similar for the viewer. But the gist here was that I would have to work out “a part I knew well,” with no unrepeatable improvising, and deliver it exactly the same, again and again. It’s one thing to do that for a song, becoming familiar with it through the process of writing, rehearsing, and recording—over a period of many months, usually—but for this action-packed minute, with only a few weeks to prepare, I would have to refine every beat into a seamless, repeatable sequence of drum events.

Meanwhile, Andy was looking into studios and soundstages, and had talked with Rush’s recent coproducer (Snakes and Arrows), Nick Raskulinecz (Booujzhe). He was excited about the project, too, and having Booujzhe onboard to supervise the recording and mixing was a major boost to my confidence in the outcome.

I had the time, the place, and the people—now I needed the drums.

For those, I simply went across the road from Drum Channel to the offices of Drum Workshop, builders of the world’s finest drums. (Handy, that.) The last two Rush tours, R30 and Snakes and Arrows, featured lavishly customized drumsets, while for the Buddy Rich tribute DW built me a beautiful set in classic white marine pearl with gold hardware.

A tribute to Drum Workshop’s artistry is that for over a year the R30 kit has been on display at the American Motorcycle Association’s museum in Columbus, Ohio—along with the Ghost Rider bike—and was a centerpiece at the instrument maker’s trade show, NAMM, then did a tour of drum clinics across the U.S. and Canada—just the drums, not me! Plus DW built thirty replicas (each costing an equal number of thousands of dollars), which found enthusiastic buyers. The Snakes and Arrows set was recently exhibited at the Percussive Arts Society’s trade event in Indianapolis, and the Buddy Rich tribute kit was bought off the stage after that concert and is on permanent display at a drum store in Pennsylvania. We only jump ahead in the story a little to reveal that the “hockey drums” would be exhibited at NAMM in January 2010, and will soon be a major display at the Hockey Hall of Fame in Toronto.

(To jump ahead just a little farther, my bandmates and I will be inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame in March of this year—along with Dolores Claman! A total, wonderful coincidence.)

(And isn’t it funny that by then the band will have been represented in the Motorcycling Hall of Fame, the Hockey Hall of Fame, the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriting Hall of Fame, and the Modern Drummer Hall of Fame—but not yet in the “official” rock pantheon? Passing strange . . . )

Between the R30 and Snakes and Arrows tours, 2005-6, I had been using a less-decorative “recording kit” from DW, in a beautiful natural wood finish. Those drums had sounded fantastic through some recording I did for Vertical Horizon’s Burning the Days album, and all of the recording for Snakes and Arrows. They had since been outdone in both sound and looks by the Snakes and Arrows touring kit, with further developments in shell design as well as the flashy Aztec Red, gold leaf, and black nickel hardware, but I suggested to DW’s drum guru John Good that we take the recording kit out of the warehouse and refinish the shells in some hockey theme.

It just seemed resourceful to me (I’m all about Reduce, Reuse, Recycle), but John would have none of that. He shook his head firmly, “We have to start from scratch.” He knew he could make something better.

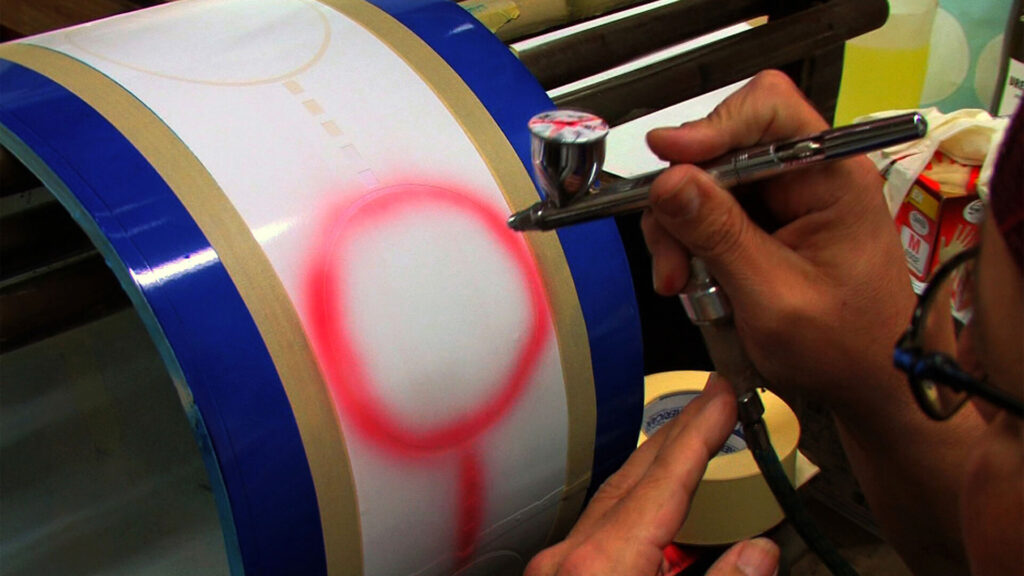

The date of that meeting was October 21, 2009, and the shoot was scheduled for early December, so there wasn’t an abundance of time. John and I met in the DW boardroom with his shell-construction foreman, Sean, hardware specialist Rich, artists’ rep (and invaluable member of my West Coast Pit Crew when my drum tech Lorne Wheaton isn’t available) Garrison, and the company’s great artist in drum finishes, Louie. Don and cameraman/editor Jose captured the scene for our “Making Of” documentary.

Back in September, in the “Autumn Serenade” period, my mom and dad were visiting, and I took Dad for his second tour around Drum Workshop. He said later, “It’s just wonderful to see people so enthusiastic about their work.” That describes the atmosphere at a meeting to discuss a new drumset.

John offered his thoughts on the selection of wood plies and reinforcing hoops he would apply to each of the different shells, and consulted with Sean on the materials and methods. Louie had already looked into the different team logos, and had some ideas for the basic finish I wanted—“ice-blue pearlescent,” we called it, like the color of artificial ice. Louie had looked up the geometry of the NHL hockey rinks, red lines, blue lines, and faceoff circles, and we agreed to try to bring that into the design.

I questioned Louie on whether the center lines were solid or dotted, and he reported, “Five of the six Canadian NHL rinks have dotted lines.” He had done his research. And he had his work cut out for him, too. Each color, on each logo—thirty different ones, on nine different-sized shells—had to be masked and sprayed separately, one tiny patch of color at a time. Every few days I would drop by the factory, with the Drum Channel cameras, to watch that work in progress. (One small preference I expressed to Louie was to give “pride of place” to the logos for teams for which I felt a “hometown” affinity: so those for Toronto, Montreal, and Los Angeles are featured in front panels.)

I had a vision of blue chrome hardware (“like icicles,” I described it to the DW guys), and wondered if that might be possible. Rich showed us some colored finishes that were powder-coated or anodized, but what I wanted had to be shinier. Since this drumset wouldn’t have to go on tour and suffer the ravages of the road, it was decided that painting was the solution—Louie would ghost a translucent blue over the chrome, and although it would be fragile, it would look like blue chrome.

Matt prepared a demo of an arrangement for me, and I started working with it—playing on the “practice kit” described in “Autumn Serenade.” Again and again I played along with that “one hot minute,” as I had come to think of it (on Day One I learned to start the iPod and drop it into my breast pocket facing outward, or while I played along, the heat building inside me had the same thermo-sensitive effect as a rotating finger, and pinned the volume).

Imagine, if you will, air-drumming as hard and fast as you can for the next one minute (try it if no one’s watching). That will give some idea of what it means to say, “I played that one-minute piece of music fifteen or twenty times a day, three or four times a week, for six weeks.”

Every few days, I would record an updated version with Drum Channel’s audio engineer, Kevin, and go away and listen to it. Then I would think, “Another drum figure would fit there—and there.”

“Gotta smooth out that transition from straight time to triplet feel.”

“Maybe I could get that hockey stomp, ‘Boom—Boom—Boom-boom-boom, Boom-boom-boom—Boom—Boom’ under that snare roll.”

(During the previous couple of tours, whenever we played in hockey arenas, I had been adding that “stomp” to the improvised part of my solo—a subtle joke you hope the keen-witted might catch. Or at least you might amuse your bandmates and crew.)

I’d go back and practice some more, then record yet another version to check out in the car and at home. About two weeks into it, Matt sent me a new arrangement, which put more of the drum action at the end instead of the beginning. Being already so “deep” into the previous version, I was a little daunted at first. But I saw what he intended, and reconfigured my part to suit.

The “Drummers Only” version of this story will appear in a more detailed beat-by-beat breakdown (drummer porn), via Drum Channel’s “Making Of” documentary. However, among the lively photos taken by my friend Craiggie (Dunkelkammer), one tells a very big story of things I have learned about playing the drums, and tried to express in educational material.

My hands and arms are flailing away, far over to my right, pounding those floor toms with all my might, while my body and face (and blazing eyes!) are focused on where I’m going next—that sixteen-inch crash cymbal in front of me. Such an alignment, an advance setup, as it were, will allow me to make the transition smoothly, under control, and be centered and balanced to keep playing at full force.

In a recent edition of Bubba’s Book Club, I wrote about a novel called The Art of Racing in the Rain, which contained thoughts about driving a racecar that I had found to be true. One of those—“The car goes where your eyes go”—has a nice relation here, as does something I learned while trying to master telemark skiing (pathetically, but earnestly, as usual). While wobbling my way down the hill, picking myself up from yet another fall, I overheard an instructor tell another beginner, “Always keep your upper body pointed down the hill.” So he’d be able to pivot his legs and arms around a stable base, I realized. “Well, yeah,” I thought, “Why didn’t I think of that?” (Because I never think of things like that—it’s why I always need good teachers.)

I think I have remarked before about riding a motorcycle on a racetrack, “If you’re in one corner, and not already thinking about the next corner, you’re in trouble.” It’s true with a car, too. And, per the above, on the drums. The heat of inspiration and adrenaline must be cooled by reason—restraint. In an interview for a motorcycling magazine, I described it as “poise in motion.” It could also be defined as “Fire on Ice”—heat tempered by conscious control. (Like that violent temper—another intentional twist on the album title, Hold Your Fire.)

Somewhere along the way, “Fire on Ice” was a title I proposed for the theme music—indeed for the whole hockey project, the whole concept. A description of the game itself, a title for TSN’s broadcasts, the visuals they could use in a montage to go with the opening theme (flashing skateblades leaving a trail of fire; a “hockey stop” in a shower of sparks; a puck blazing like a meteor and scorching into the goalie’s glove in a sizzle of smoke). The title had been used for a book about one team’s Stanley Cup win, for a figure skater’s autobiography, and—I was told—for an Ice Capades show, but not for anything like this. However, no one else up the ladder at TSN seemed to take up the vision, and it wasn’t my place to do anything more than share the idea. So I decided to use the title for my own story, at least, and maybe Drum Channel’s documentary.

Another vision I had was for Booujzhe to produce an “extended mix” of that one-minute performance, in the spirit of the over-the-top dance mixes of the 1980s. We could deconstruct the orchestration and experiment with rhythmic loops and such—have fun with it, and easily make it several minutes long. With that in mind, I decided to work up a “quiet version” of the theme, in which I would minimize the drum part and play it softly, with a view toward adding percussion overdubs for texture and atmosphere. Perhaps TSN could use that as an “outro” theme, under their credits, or at least, the elements would be useful in that extended mix.

Working on that “Quiet Version” gave me a nice physical break from the “Loud Version,” and—perhaps surprisingly—took just as much painstaking labor to refine. It is less “pyrotechnical,” drumming wise, but required a delicate touch, superhuman restraint (merely keeping time through the “solo” sections), and perfect control and feel—the kind of approach I had worked on in my studies with Peter Erskine in 2008, so it was great to have a chance to express it.

December 7, 2009, the Big Day, was uncharacteristically rainy for Los Angeles, but as I drove east to Hollywood, hissing along Sunset Boulevard toward Ocean Way Studios (where Booujzhe and my bandmates and I had mixed Snakes and Arrows), my excitement was certainly not dampened.

One of Frank Sinatra’s best television specials, “A Man and His Music” (1965), opened like that—a shot from a distant rooftop of his sleek, elegant Dual-Ghia driving through a dark, rain-wet studio lot and up to the door of a soundstage. Nothing and no one else around, Big Frank walked from the car and opened a door into a large, bright studio full of musicians. That’s how I felt pulling up to Ocean Way in my sleek, elegant Aston Martin—though unlike Frank’s suave entrance, I had to run through the rain. (No one can ever be as cool as Frank Sinatra. As his friend Dean Martin put it, “It’s Frank’s world—we just live in it.”)

The above photo shows me giving my “speech” to the musicians before we began—about what this piece of music signified to Canadians. “Just remember that every man, woman, child, granny, moose, and beaver in Canada will hear this performance.”

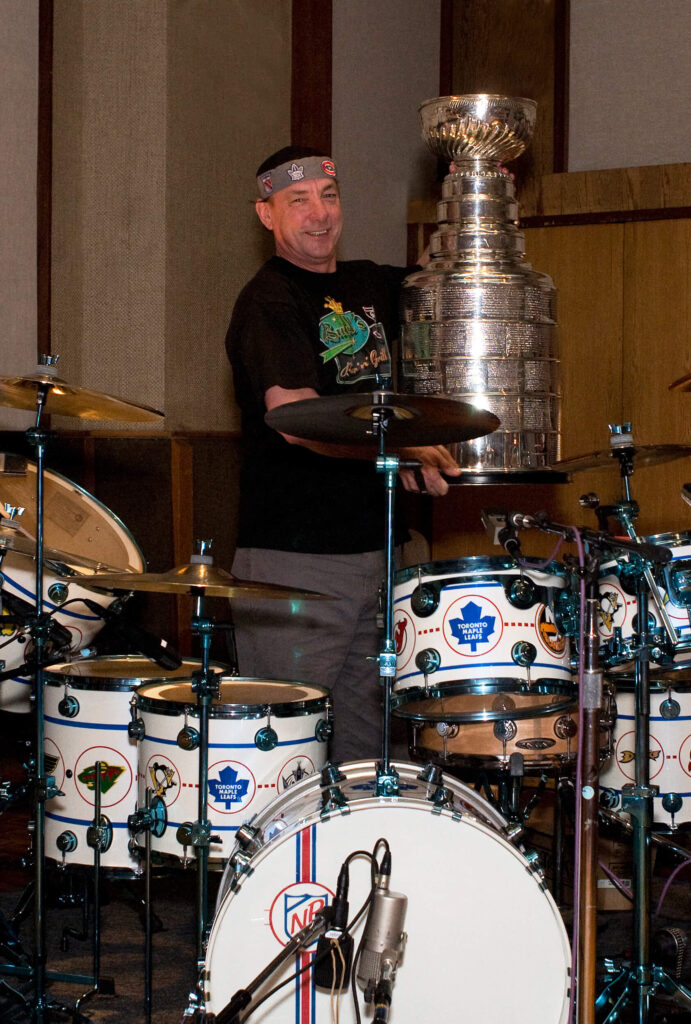

And . . . while we recorded, we were inspired by the presence of a sacred hockey icon, the real, actual Stanley Cup, sitting in the middle of the room.

It happened that a representative from the Hockey Hall of Fame was in town to display the Cup at a Los Angeles Kings game the previous night, and he was able to bring it by the studio for a few hours.

The Cup’s traveling companion and attendant, Craig, allowed me to lift that treasured Canadian symbol (more than a hundred years old) out of its road case and hold it up high (it weighs thirty-five pounds), like I was a hockey player whose team had just won the Stanley Cup. The earliest inscription was inside the bowl, for a game in 1904, in which “The Kenora Wanderers Beat Ottawa.” Every winning team since was engraved on silver bands around the sides (they add another circle when it gets too full). I stood behind my drums for the cameras, holding up that Cup, and thinking, “Take that, bullies from fifty years ago.”

Thanks to that inspirational presence, the ace musicians, Matt’s charts, my preparation, those state-of-the-art drums, and Booujzhe—who produced a magnificent drum sound, and worked well with Matt to get the best out of the orchestra—we were able to get the music recorded pretty quickly that morning. First we did the “Quiet Version,” then the “Loud Version.”

Then the drums had to be moved to the soundstage, and were broken down by Garrison, his partner in my West Coast Pit Crew, Chris from cymbal-makers Sabian, and some of the Drum Channel crew (I told Don later that it was wonderful to see him, the president, with his rain-wet hood over his head as he helped with the loadout).

My one regret is that I was called over to the soundstage for the filming just as percussionist Brian Kilgore was preparing to do his overdubs. When I heard the “Loud Version” later, the tympani notes he added were just perfectly placed, either reinforcing my parts or finding gaps I hadn’t imagined (like after my little splash-cymbal slapstick), and the orchestra chimes gave it a proper, classical grandeur. But in those parts, Brian was just playing (however perfectly) what Matt had written. For the “Quiet Version,” the percussion parts would be entirely improvised, and that’s where Brian really shone. On my way out, I had suggested perhaps he could try bongos and congas, and that I was looking for a certain “Lalo Schifrin” vibe (original Mission Impossible theme). When I got back, and Booujzhe played me what they had done, Brian’s contributions on shaker, rainstick, and bongos were creative, tasteful, and atmospheric. What a pleasure it was for me to work with musicians of that caliber.

I had mentioned to Andy early on that the film people couldn’t expect me to do limitless takes of this performance. As I said, there was no “faking it,” and I knew from my rehearsals that my One Hot Minute was a killer to keep repeating.

But they too were professional and well organized, and managed to keep it down to eight separate performances, for different lighting and camera angles. Again, I just played my carefully orchestrated and rehearsed part as well as I could, while they did their work.

Having completed the film shoot, and an interview in front of TSN’s cameras, by late afternoon I was back at Ocean Way, sipping a Macallan in the control room while Booujzhe started mixing. The hard stuff was over now, and I was happy just to sit back and listen to the results, over and over, and later that night, have a CD to take home with me.

The rain had tapered off, but the neon and streetlights reflected on the wet pavement of Sunset Boulevard. Now I could finally start to get some perspective on the day’s events, and I realized it had gone, well, perfectly. Thanks to all that preparation, and to a great team of people, I had delivered the performance I wanted as accurately as I could have hoped (and quickly too). I smiled to think that, all told, it had been one of the great experiences of my life. How rare and wonderful to be able to “think that out loud”—to make such a plain statement of superlative fact, without exaggerating or “playing to the crowd” one little bit. All of that work had been worth it.

One of Craiggie’s photographs that really spoke to him and me is an image only a friend could have captured. Between takes at the film shoot, I was looking over at Craiggie on the sidelines, smiling as if to say, one Canuck to another, “Pretty neat, eh?”

Or that smile might be saying, “Take that, bullies from fifty years ago!”