A more creative and satisfying undertaking for both Bubba and the Professor was putting together a new calendar for Bubba’s Bar ’n’ Grill—something they could both get their teeth into. As we have noted before, few activities are as enjoyable and rewarding as making things—meaning things you can hold in your hands, with pride, and even look at on your wall all year, with pleasure. (Bubba and the Professor agree that pride and pleasure are a good combination. Both in moderation, of course. We are Canadian.)

Back in the autumn of 2011, we had a little time at home, and a little ambition (sometimes a great combination), and with our lifetime art director, Hugh Syme, put together the first Bubba’s calendar. We were sure we had created something beautiful, entertaining, cool, and affordable—surely everyone would want one, and to buy lots more for their friends at Christmas.

But alas, sales were disappointing—we gave away more copies than we sold. The world let us down again. (As it still does often enough to keep us humble . . . )

The following autumn we were out on the Clockwork Angels tour, so didn’t have the leisure to try to match the first calendar’s combination of carefully chosen images and text blocks. However, this past September we were just settling into our sabbatical frame of mind, and were inspired to try another calendar. Brother Danny, who has been our prose editor for the past couple of years, helped in selecting the images and text passages, and once again Hugh Syme stepped up with a brilliant design.

The front cover combined a “far and away” shot taken by Brutus in Germany (I titled it “Der Zigzags”), with Hugh’s additions of a more dramatic sky, and the shapely rear of Bubba’s 1963 Split-Window Corvette.

On the back cover, we were delighted to have another chance to present that all-time favorite portrait—or at least Bubba’s favorite—the one that opens this story.

Nice things happened to make this calendar rewarding. One day in October I was visiting Don Lombardi up at Drum Channel, and mentioned that I had put the calendar up for sale online, but early orders were disappointing. As a good friend and booster (and the founder of Drum Workshop), Don immediately picked up the phone and called the president of Guitar Center—a chain of almost 300 stores around the United States that sell musical instruments. After some consultations, they eventually agreed to order 1200 calendars to spread around their stores. The bad news was that the price would not be enough even to match my costs, and they are on a “sale or return” basis, so I will see an unknown quantity coming back. But never mind—at least people would have a chance to find them.

And there were other rewards—many grateful recipients of the copies I sent to friends wrote to thank me. One day I received a note from Jamie Borden, who combines the unlikely Vegas careers of dedicated cop by day, and passionate rock drummer by night. (I smell another sit-com!)

Jamie told me he had arrived home from a trip just before Christmas, and found his whole extended family baking up a storm, with decorations everywhere, and his home filled with every true spirit of the season. Amid all that, he opened our calendar and went through it, describing to his loved ones what he knew about the stories behind the images, and reading some aloud.

Naturally, that was exactly the kind of heartfelt appreciation from a dear friend that could make the project feel entirely worthwhile.

In a letter (probably to Craiggie) just after Christmas, we were reviewing that hectic season, the three weeks we had dedicated to shopping for gifts, getting them shipped, planning menus for Chef Bubba, shopping for groceries, and cooking for large gatherings on Christmas Eve (ten guests) and Day (fifteen—with a Flintstones-sized turkey).

We concluded with what felt like the “score.”

“Me: Grateful.

Others: Grateful to me.”

That seemed like a fair result.

Okay, that surreal segue comes with a smile, and courtesy of friend Craiggie. It delights us to imagine it on a sign in front of a church.

As a career choice, piracy didn’t work out for us (too much competition, these days!), so we’re going to keep on being Bubba and the Professor. (Not that we have any choice.)

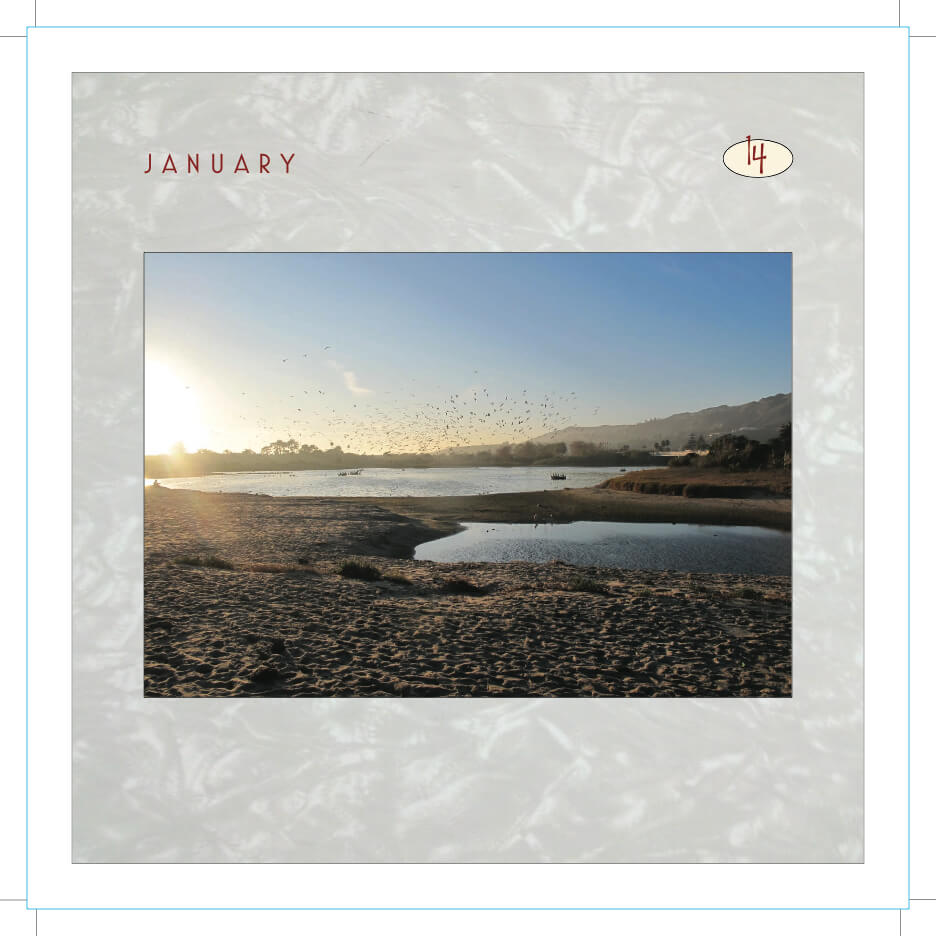

Fortunately, one thing we do have in common is that both of us like road trips, the longer the better, on two wheels or four. In early January, wife Carrie expressed interest in a two-night family trip to San Francisco, wanting especially to see the David Hockney exhibition at the de Young Museum. While the girls preferred to travel by air, Bubba and the Professor willingly chose the 850-mile return drive in their Aston Martin Vanquish. Interstate 5 is typically the quickest way north, by an hour or so, but California 101 is more scenic and “characterful.” Best of all, if time permits, there’s Highway 1 between San Luis Obispo through Big Sur to Monterey—one of the world’s greatest stretches of road.

Photo by Matt Scannell Esq.

However, that route pretty much demands an overnight somewhere along that sublime coast, so this time we would be satisfied with six hours or so on 101, to get to the hotel in San Francisco before the girls. No problem. Leaving in the pre-dawn darkness and heading up the coast as the sky pearled into light over the calm Pacific, the miles passed pleasantly. North through Ventura, Santa Barbara, and San Luis Obispo, we decided to pause for lunch at the In-N-Out Burger in Salinas (John Steinbeck’s hometown, with its “National Steinbeck Center,” described in Ghost Rider).

In that midwinter season, the hills of Central California should have been velvety green from the winter rains, but they wore their midsummer brown (what I once called the “lion-colored hills”), looking parched and shriveled. Through December and January we should have received much of a year’s worth of rainfall—but there had been almost none. The drought in California was off the charts—not something like half or three-quarters, but a mere single-digit percentage of average amounts. The worst in recorded history.

In the Los Angeles Basin, the dreaded Santa Anas, or “devil winds,” had been sweeping in from the high desert, growing hotter and drier as they descended. In a time of such drought, they vastly increased the danger of wildfires. A couple of bad ones had already flared up, and it was likely only the beginning of a dangerous season.

(Some wag once defined the four seasons in Southern California as drought, wildfire, flood, and mudslide. This year we were only getting the first two—so far.)

The smoke in the air also worsened the effects of the Santa Anas. In the opening of Traveling Music, we told about the unpleasantness of the devil winds—rasping in your sinuses, your throat, your eyes, your skin, and your mood.

In the novel Red Wind, Raymond Chandler defined the Santa Anas for all time:

There was a desert wind blowing that night. It was one of those hot dry Santa Anas that come down through the mountain passes and curl your hair and make your nerves jump and your skin itch. On nights like that every booze party ends in a fight. Meek little wives feel the edge of the carving knife and study their husbands’ necks. Anything can happen.

The climate of the Bay Area, 400 miles north, was cooler and usually wetter—though they had their own “devil winds,” the Diablos, from time to time. And their drought at that time was equally severe. A friend living in the nearby Santa Cruz Mountains told me they usually received 70 inches of rain—that year they’d had five.

During our visit to Tony Bennett’s “city by the bay,” we had cool, sunny weather, and all had a good time—a great playground in Yerba Buena Park for Olivia, and an unforgettable meal for Mom and Dad at Michael Mino’s restaurant.

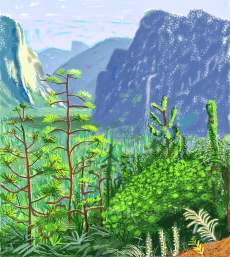

And there was the uplifting experience of viewing “A Bigger Exhibition,” a monumental installation of recent works (this century) by David Hockney. British-born (1937), Yorkshire bred, and a longtime resident of California, Hockney rose to prominence in the pop art school of the ’60s, then grew into his own mature style of what Bubba and the Professor (amateur art critics who know the lingo) might call “representational expressionism.” Over the years we had seen his work at the Tate Gallery in London, and at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, and had always enjoyed it, in a “lukewarm” way. However, after viewing this exhibition, we came away convinced David Hockney is the greatest living visual artist—a worthy heir in skill, range, and vision to his self-described hero, Picasso.

The works on display at the de Young represented an immense variety and quantity of art—yet covered just over a decade, by an artist in his seventies. That alone was inspiring. Works were grouped according to medium, across the full spectrum of an obviously passionate, even obsessed graphic artist—entire galleries of charcoal sketches, watercolors, oils, acrylics, and color sketches created on iPads and iPhones. (He was quoted in one of the descriptions that the neighbors in his Yorkshire village jokingly asked if it was true he was making art on his mobile phone. He replied that no, he simply sometimes used his sketchpad as a telephone.)

iPad drawing printed on paper (6 sheets)

Those creations were gorgeously printed out on scales ranging from small studies to multi-canvas assemblages that filled whole walls—overwhelming to stand before. Some of the combinations echoed his longtime cubist fascination—famously expressed during the ’70s by collages assembled from multiple Polaroids and, later, high quality prints arranged to depict a fragmented, but entire view. He called them “joiners.” We could see that approach echoed in more recent filmworks, in which he used multi-camera digital videos on gallery-sized grids of screens to show fragmented views of driving through a Yorkshire landscape, or of jugglers practicing.

Hockney’s recent visual preoccupations were apparent in several series of portraits, and many vast landscapes of Yosemite and East Yorkshire. Being familiar with both of those areas, we could only wonder what the experience was like for those who weren’t—did those great paintings evoke the same degree of appreciation if you hadn’t seen the “source material”—the actual landscapes they attempted to capture?

Bubba opined, “Hmm, no—other folks just can’t see it like we do. ’Cause we can say, ‘That is exactly how a Yorkshire lane looks on a rainy day.’ It’s one thing to say a piece of art is beautiful, but a whole lot greater to say it’s beautiful and true.”

The Professor said, “Whoa, Bubba—you are deep today.”

Early next morning, at 5:30, we were on the way back south from San Francisco. We drove through the endless dark suburbs to San Jose, then, as the red disk of sun inched up before us, into the farmlands of the Salinas Valley. We stopped in Salinas again, for breakfast at the Black Bear Diner, a Western chain of traditional small-town eateries with nostalgic décor, music, and menus. Always friendly and good, in our experience.

(Roadcraft tip: As professional travelers, we have suffered more intestinal distress from undercooked eggs than any other cause. We love soft-boiled, sunny-side-up, and especially poached eggs, but we make those at home. When traveling, we recommend over-medium, or scrambled.)

Brown dirt, White sky

Just over a week later, we set off on another long road trip, this time 500 miles north, to a dot on the map called Willows, California. This would be a different kind of “traveling extensively for research.” Once again we started north along the dark coast through Malibu and Ventura County, then turned inland to Ojai, and one of our all-time favorite roads: California State Route 33. On two wheels or four, that little road has just about everything, and rarely do we share it with any other traffic. The first seventy miles or so are a looping, challenging delight, through the chaparral and pines of the Santa Ynez Mountains and Los Padres National Forest.

Up toward Maricopa the country flattens out into irrigated hayfields, then a long stretch of oilfields—the old-fashioned kind of “nodding bird” pumps. Somehow such an old-tech industry had a quirky charm, and certainly didn’t blight that dusty landscape. No doubt the dreaded, more modern fracking is going on beneath the surface.

That stretch of Route 33 is not especially scenic, but the driving is fine, on a straight, empty two-lane. In good conditions, that kind of desert road can sensibly be driven at 80 mph—but of course the signs dictate otherwise. So we put up our radar detector, to stand guard against “surprises” from the California Highway Patrol. A speed trap was unlikely, but the odd time you might encounter a randomly patroling cruiser coming the other way. We hate that conversation.

The crossroads of Blackwells Corners has long billed itself as “James Dean’s Last Stop.” On September 30, 1955, while driving his Porsche Spyder to a racetrack in Salinas, he apparently bought gas, cigarettes, and an apple. A few miles farther on, at the intersection with California 46, he was killed by a Ford sedan, whose driver failed to see the tiny silver car in a glaring sun. Dean was only twenty-five—and none of the three movies that would make him an enduring legend (Rebel Without a Cause, East of Eden, and Giant) had even been released.

Around there, at the quaintly-named town of Kettleman City, we surrendered to the “mileage-disposal unit”—Interstate 5. We had covered half the journey, 250 miles, on the backroads, and now needed to make some time. We also changed defensive tactics: instead of the radar detector, we turned on the cruise control. In previous Roadcraft references, we have advised that speeding on American interstates is generally a losing gamble. Just set the cruise at an acceptable “eight over,” and relax.

The above photograph of a bleak Central Valley interstate scene makes a good contrast to other images we have shown of “idyllic” California—the evening sky with palm trees, and the Coast Highway. In the heart of the Central Valley (which grows something like thirty percent of America’s produce), the drought left the fields, leafless orchards, and hills nearby parched and brown. Occasional amateurish signs along the freeway pleaded “Stop the Congress Created Dust Bowl.”

I knew those signs, and many others with similar messages, referred to the constant struggle over water rights in such “lands of little rain.” In semi-desert regions like the Central Valley (all of Southern California, for that matter), the combination of unlimited sunshine with a supply of irrigation water was a treasure beyond price. As Mark Twain explained, “Whisky is for drinking. Water is for fighting over.”

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

As I cruised along I-5 at precisely 78 mph, I saw the farther hills on both sides, and the sky above, were ghostly white. That was the smoke drifting downwind from the big Colby fire, in the San Gabriels near Glendale—about 200 miles away. The sun burned through, but the light was harsh and glaring on windshields in the opposite lanes.

The brown, twiggy balls of tumbleweed that would usually cluster along the windward fences had been gathered into enormous stacks. That made a monstrous image of what they really represented—not a romantic symbol of the Old West, but an invasive species and pest. Like kudzu in the South, or purple loosestrife in the Northeast, tumbleweed is an alien invader, Russian thistle—thought to have arrived from that country in the mid-19th century with wheat seeds. Another monstrous presence loomed over a few enormous cattle feedlots, which give off one of the vilest stenches on earth. Driving by them on the leeward side, we try to hold our breath. Mile after mile, the overall impression was of a flat, arid, rather bleak landscape subjugated by vast factory farms and intricate irrigation canals.

Still, it was what it was, and for us, the drive was a perfectly enjoyable way to spend a day. Traveling for research. And the destination was inspiring, too—Thunderhill Raceway, for the next day’s Aston Martin club trackday. A racetrack is where a car like the Vanquish can properly “express itself,” of course—not on a freeway or suburban boulevard. (Not that it isn’t nice to drive there, too!) On winding roads along the coast or in the mountains, and on racetracks, the car has a “sporting” character, powerful and responsive. Yet it also excels as a “grand tourer”—after a 500-mile drive, we climb out feeling fresh and free of pain. A little bleary-eyed and stiff, of course, but not hurting anywhere. When people ask us what the Vanquish is like, we simply reply, “It is everything it ought to be.”

Our friend Matt Scannell once said he liked how when a stranger looked at one of our cars admiringly, and described it as his (and sometimes her) “dream car,” we would simply say, “Mine too.”

Because of course these are all our dream cars, and Bubba and the Professor both admire them and use them—long journeys and racetrack outings for the “modern supercar,” and plenty of backroad exercise for the “classics.” (We have put over 20,000 miles on the DB5 alone, in six or seven years—which included long absences while touring and recording, and a year off the road for a mechanical rebuild.)

Regular readers will notice that we have reversed the stance put forth in the previous story, “Angels Landing.” We had decided only to picture the Vanquish from the rear, as part of the scenery, not to excite any negative reactions. Brother Danny pointed out, wearing his editorial hat, and Bubba and the Professor have come to agree, that the spirit of “sharing” that inspires these stories does not need to be concerned about those who are incapable of sharing the joys of others.

Regarding such dark souls, insert your own expletive of dismissal . . .

Photo by Head-On Photos

For Bubba and the Professor, our first experience on a racetrack was in the mid-’80s, at the Circuit Mont Tremblant in Quebec. We attended the Jim Russell Racing School (still operating, we are glad to note), one year for the Formula 1600 course, the next for the Formula 2000 class (with more power and aerodynamic wings that made the car a whole lot quicker and more serious—scary, even).

To readers with zero interest in motorsports, we promise to be as brief and considerate as possible. (After this latest trackday, we scribbled in our notebook, “Such an experience, such a scene, to try to describe—without being boring!) First of all, a roadrace track is different from the common stereotype of, say, a Nascar oval. Sometimes when we tell people we were at a trackday, they will say, “How fast did you go?” That’s not what it’s about. The typical layout might be two or three miles of loops and bends, a highly technical combination of turns in varying radii and camber, plus elevation changes (ups and downs). Short straightaways might allow you to accelerate beyond 100 mph for a few seconds, but then you’ll be braking hard into the next turn, and balancing the car to take it as quickly as you can. On faster tracks, like Willow Springs, you carry a lot of speed through several bends, and have to brace yourself accordingly. After a long day of those “lateral Gs,” we will hurt for days.

On a trackday, there is no racing between drivers (or at least, not “officially”). The cars are sent out at intervals, with passing only permitted in specific “safe zones.” You race against yourself and the track—which, unlike most public roads, is not designed to work for you, but against you. The tricks have names like “off-camber,” meaning the corner banks away from you, or “decreasing radius,” where a turn suddenly gets sharper instead of opening up. As you push your car, and its tires, to the limits of friction, smoothness is key—every input with hands and feet has to be “delicately deliberate.” At best, it’s a dance on the edge of control, and when you string together a series of smooth, fast laps, it feels very good.

Photo by Loris Ourieff

Comparable to our drum studies—or early motorcycle training—the basics we learned at the beginning continued to be supplemented by other instructors. (For example, on two wheels, we attended the Freddie Spencer High Performance Riding School in Vegas, described in Ghost Rider. Which reminds us that we had another kind of split personality then—three ways, as we recall—traveling on that journey, and attending the school, under the alias John Ellwood Taylor.)

After moving to California in 2000, we discovered that informal trackdays for cars or bikes were common and inexpensive, and started attending one or two every year. (The Professor insisted that the risk of injury on a racetrack was too high on two wheels, so we stayed with cars.) Expert instructors were usually on hand, and we always liked to have them ride with us for a few laps—often in the early afternoon, after we’d had a chance to try it “our way” for a while. Inevitably they would give us enough little tips to make the rest of our day quicker, and raise our game for the next time.

Photo by Head-On Photos

Over the years we had the opportunity to challenge most of California’s racetracks, like Laguna Seca, Willow Springs, the Auto Club Raceway in Los Angeles, and our favorite, Thunderhill Raceway in Northern California. The Aston Martin club event is always held there, and in January, when we are never touring (explained before, “Because, um, motorcycling?”), so we haven’t missed one since 2006.

As always, this one was a learning experience. (“For research,” again.) As we have moved up through successive modern Aston Martins, from the DB9 to the DBS, and now the Vanquish (the old DB5 was a one-time “parade” outing), we have to admit we have reached our peak of capability—maybe a little beyond. In one late morning session, we “overcooked” it on one corner, and the car went sliding sideways across the track (what Brit motojournalists would call a “lurid slide”). We corrected it enough to drive straight off into the dirt infield, rather than spinning, but as we went slewing into the dusty gravel (throwing up a mighty cloud of dust, we know from witnessing other “off-track excursions”), we were feeling plenty . . . “alert.”

Trying to steer or brake would only make things worse, so it was necessary to counter that natural instinct. We just held on, mentally repeating, “Don’t do anything, don’t do anything,” until the gravel slowed the car enough to let us steer back onto the track.

We made sure that didn’t happen again. For the rest of the day we kept the car on the track, and reeled off some satisfyingly consistent laps.

Bubba gets high on the adrenalin; the Professor likes the concentration and precision. They both have a very good time.

The longtime organizer of the Aston Martin event is George Wood, a district attorney up in the Bay Area. (We bought our DB5 from him, back in 2006.) In his DB9, George is a very enthusiastic participant himself, and once crowed, “I live for trackdays!”

Bubba and the Professor would almost agree—but between the two of us, we live for so many things. Cars, motorcycles, birds, words, music, landscapes, cooking, family, art, learning, roadtrips, and . . . single malt whisky.

After all these years, now that we are a sexagenarian, it’s still rather amazing that we can find enough “common ground” to coexist. You could say the same about an enduring marriage (or rock band!), and perhaps the same qualities apply: we are just enough alike to be willing to share the same time and space, but different enough to sometimes surprise each other.

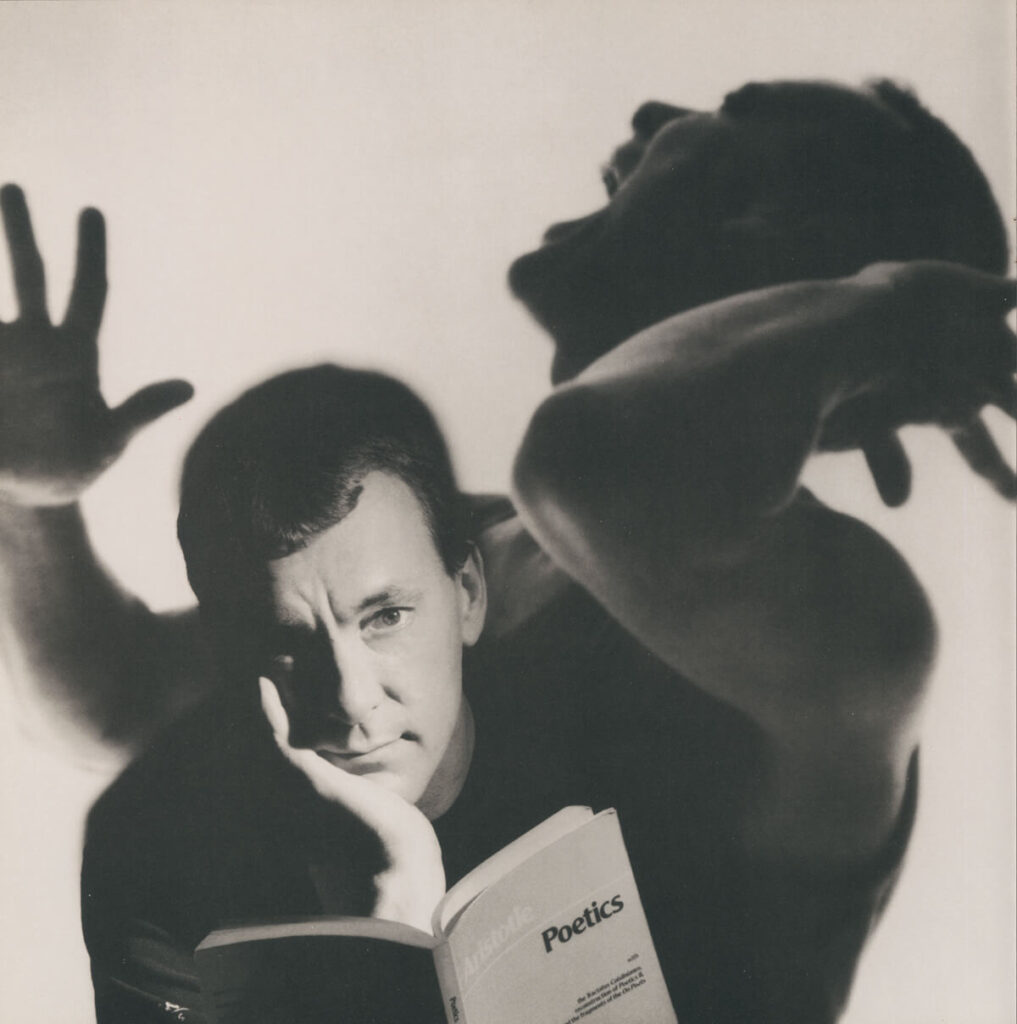

And here is a surprise testimonial from the past. Twenty years ago Andrew MacNaughtan collaborated on another portrait, for the Roll the Bones tourbook. We hoped it might represent what we vaguely felt were different facets of our character. Back then we weren’t thinking of ourselves as Bubba and the Professor, but of course that’s exactly what Andrew captured. The Professor held up Aristotle’s Poetics, regarding the camera with a look of wry tolerance, or resignation, while in the background Bubba danced like a maniac.

That’s us—I mean me.

When Bubba and the Professor were kids, it would have been Bubba who said, “I want to play the drums!”

The Professor would have replied, “Fine, but we’re going to study and practice hard, and be as good as we can get. And never stop trying.”

And so they united in a common goal. A few years later, it was Bubba who complained, “I want to quit school and be a full-time musician.”

The Professor would have said, “Fine, but we’re going to give it everything and more, even chase across the ocean and be poor and desperate, until we get established. Then we’re going to get the education we’re missing now.”

Still later, Bubba said, “I want to ride motorcycles all over the place!”

The Professor said, “Fine, but we’re going to learn to do it well, and wear all the proper gear, all the time. And I’ll pick the destinations and routes—where we might learn something.”

Some years passed, and Bubba said, “I want a ’63 Corvette Sting Ray, like we used to dream of when we were ten! Remember how we used to draw that car all over our schoolbooks—until we started drawing Keith Moon’s drumset instead?”

The Professor said, “Fine, but first we get an Aston Martin DB5—because that’s what we dream of now.”

And so it came to pass that “on days like these,” when the day starts to fade toward late afternoon, and it’s time to pause and read over the day’s work, you can always count on Bubba to say, “Hey Perfessor—how about a drink?”

The Professor will reply, “That would be nice, Bubba. I’ll join you.”