First I thought of Utah. (And when you’ve got an opening line like that, you almost want to stop and let the reader take it from there.)

I had five days in early June to travel somewhere on my motorcycle, to make my Last Getaway before settling in with my wife Carrie to await the Blessèd Event—the birth of our baby in August. After that, I wouldn’t be going anywhere for a while.

So I thought of Utah. Do some motorcycle touring and hiking in the national parks like Zion, Bryce Canyon, Arches, and Canyonlands, and maybe stay a couple of nights in one of my favorite Western towns, Moab.

But as my eyes wandered through the road atlas (the Book of Dreams), they were drawn to a corner of Wyoming, an area colored in green that bordered Montana and Idaho—Yellowstone National Park. It was the only major park in the American West I hadn’t visited, and one of the few in the whole country (those two in northern Alaska are going to be really hard to get to!).

I had tried to visit the Yellowstone area on my Ghost Rider travels in October 1998, but was turned back by early snow in Utah, and headed south instead. Since then, I had just never made it that way. Motorcycling on Rush tours had taken me all over the country several times, but Yellowstone was far from any cities with sizable concert venues (the only possible scenario would be a day off between Salt Lake City and, say, Boise, but that rare combination had never occurred).

So yes, I wanted to go to Yellowstone all right. I looked up its distance by road from my Southern California home, and frowned when I saw that it was over 1,000 miles. Hmm. That’s far. With only five days to get there and back, and wanting to spend some time in the park, it was a bit much, really. But . . . I had ridden 1,000 miles in a day before, and anything close to that would make a good start on the first day. Maybe I could do it.

Grand Teton National Park was right on the way, too—adding the possibility of two new national park “passport stamps” for the growing collection.

The more I thought about it, the more I wanted it.

So after some feverish planning and packing, I set off on Monday, the first of June, at a little before 5:00 a.m.—a time when it is usually possible to get on Interstate 10 and make it across the width of Los Angeles before the Monday morning gridlock sets in. I turned northeast on I-15, across the Mojave Desert, and those long empty miles passed pleasantly and easily.

Only the cities loomed as potential interruptions to my rapid progress—after escaping L.A. so early, I would hit Vegas by 9:00, with its heavy traffic and ceaseless construction. And though Las Vegas can be a dramatic sight by night, it does not look its best in the morning (I guess few cities do).

Straight four-lane highway arrowed for hundreds of miles across the open desert, up past Mesquite, Nevada, to the northwest corner of Arizona, where it suddenly curved up into the Virgin River Gorge. That spectacle ought to be more celebrated, though admittedly, the rocky majesty is somewhat marred by having an interstate hacked and blasted through the middle of it!

Running north now, up into Utah, the creosote and Joshua trees of the Mojave gave way to the sage and juniper of the Great Basin. Snow rimmed the higher peaks and dark cumulo-nimbus clouds bulged in every direction. Black veils of rain trailed below the clouds, slanting to windward, and often disappearing into thin air—the so-called virgas that evaporate before they reach the parched land below. Only a few scattered drops struck my faceshield.

As the miles and hours went by, with occasional breaks for gas and water (in and out), I was starting to think about stopping to eat. On shorter riding days I will often forgo lunch, and just keep moving toward the “somewhere” I’m trying to reach, but on a deliberate marathon like this I wanted to make sure I felt as good, and as sharp, as possible. With few dining options in those far-flung Western service areas, I had brought a couple of bottles of water, and some ham, cheese, and bread to make my own sandwich. I planned to stop at a roadside rest area and relax at a shady picnic table, having the best lunch I could, yet in the shortest amount of time.

From passing through southern Utah on my way cross-country a few years previously, I remembered some nice rest areas along that part of I-15, but I wanted to hold out until I got closer to Salt Lake City—the next obstacle of potential traffic and endless road construction. Unfortunately, in central Utah the department of highways seemed to be experimenting with an ill-advised “partnership” between the public and private sectors—at least that’s what the signs called it. When I pulled off at a couple of different places signed as “rest areas,” there was a truck stop and a fast food outlet with big paved parking lots, and one cruddy metal picnic table beside a dusty offramp, without even any shade. Phooey on that.

In Utah I had crossed into the Mountain Time Zone, and lost an hour, so it was close to 2:00 when I gave up on the “rest areas” and took a random offramp, pulling up beside a boarded-up family restaurant (always a sad sight—as I have described it before, “the death of a dream”). I had covered 600 miles in eight hours (averaging 75 mph, even with gas stops and such—a good pace). My radar detector’s earpiece defended me against overzealous law enforcement, though Western highways are generally posted at a reasonable 70 or 75 mph anyway, and a couple of stretches of Utah interstate offered an “experimental” 80 mph limit. So I didn’t really need to exceed the “eight-over-the-limit” formula to make good time. Sometimes I just wanted to.

Pulling the bike back on the centerstand, I unpacked my lunch supplies, then sat on the crumbling steps in the shade of some scruffy cottonwoods. I struggled out of the inner layer of my riding clothes—the temperature had climbed from the pre-dawn 50s to the 90s in Nevada, then down to the 60s again as the elevation rose, then up to the 80s by that offramp in central Utah. It’s hard to dress for that range, but by overdoing the layers, then peeling off the plastic rainsuit when it was warmer, I had felt pretty comfortable most of the time. It felt good to strip down to the basic leathers and T-shirt, then assemble my ham and cheese sandwich. I ate it slowly, letting my eyes go out of focus for a few minutes.

My nominal goal for the day was Logan, Utah, as that would represent the end of the interstate riding, and put me in easy reach of Yellowstone for the following day. And at 790 miles, it was plenty far enough. I cruised the neat-looking Main Street, and consulted my GPS screen to compare the options, then decided on the Best Western. I swung a weary leg over the saddle and went inside to register, then parked in front of my room. After carrying my luggage inside, I poured a Macallan on ice into a Best Western cup of finest plastic, then took a self-portrait of my weary, saggy face. It was not a pretty sight, and won’t be shared with others—but I wanted to remember.

Following the desk clerk’s recommendation, I walked down Main Street to the Bluebird Restaurant, and sat down to catch up on the day. My first journal entry, after noting the location and mileage, was, “Every detail I think of putting down seems inconsequential, yet it is the sum of those details that made the day.” Well, ain’t that the truth!

Logan, Utah, sat at 4,535 feet, surrounded by the high rounded mountains of the Bear River Range, their peaks still streaked with snow. Behind the motel a roaring stream strained at its banks, a loud torrent swollen with that same snow, slowly thawing. Ever since I had turned off the interstate and into the mountains, the greenery had overwhelmed me—because once again, as I described in Roadshow, I had become used to the arid economy of Southern California’s semi-desert climate; my eyes were accustomed to what nature writer Mary Austin called “The Land of Little Rain.” Whenever I re-encounter lush green fields and woodlands of dense leafy trees, they take me back to the surroundings of my childhood in Southern Ontario, and I feel it deep in my being.

Mountain towns have a special character, at least partly from being dwarfed by their surroundings, the modest buildings huddling together as if for protection beneath a rising landscape, and partly from the weather—they tend to get a lot of snow in winter, and fierce thunderstorms in summer. Being nestled in a valley, closed to the natural sprawl of desert or prairie towns, plus inhospitable weather and isolation, tends to keep such towns smaller, so the lodgings and restaurants are more often central, a pleasant walk apart. A few North American examples would be Banff, Alberta; Nelson, British Columbia; Littleton, New Hampshire; Gunnison, Colorado; Taos, New Mexico; Ketchum, Idaho; and Creel, Mexico, on the rim of the Copper Canyon—all those places, and many more, share a certain “splendid isolation,” and a bracing edge to the thinner air of higher elevations. I have long wanted to live for a while in one of those mountain towns. Maybe someday.

Mormon towns have a special character, too—neat and well tended, centered around a spectacular temple (I can’t help but admire their sacred architecture), and the small family businesses apparently thriving, unlike the main streets of so many other American towns. The storefronts look quaint, and sometimes a generation or two out of time: a sub shop called “Logan’s Heroes,” a clothing store selling prom dresses, formal wear, and “missionary attire” (suits for the young Mormon males who are sent away to proselytize, then return as so-called “elders”—all over Mormon country I would see homemade signs like, “Welcome Home Elder Berry”). Along the Utah interstate that day, I had laughed out loud in my helmet as I passed a pickup, its rear window decorated with one of those oval, black-on-white “destination” stickers that commonly read “YNP,” for Yosemite National Park, or “OBX” for the Outer Banks of North Carolina. This one read “Gentile.”

Apart from a couple of old cinemas, still apparently operating, the bright spot on Main Street was the Bluebird, an old diner-style family restaurant. True to the Mormon proscriptions of alcohol, tobacco, and coffee (a prescription, to this gentile), the Bluebird offered a decent American menu, but served nothing stronger than lemonade.

The décor was fantastic, though: high ceiling, mosaic tile floor, marble-and-mirrored soda fountain with a long row of stools, wood paneling, wooden chairs and tables. The customers were well-scrubbed families, or groups of neatly-groomed youths, all caucasian, probably mostly Mormons. With all that Norman Rockwell Americana, and the all-American menu, I was amused to read in the menu’s “historical notes” that the Bluebird was now owned by the Xu family. Truly, America is the land of Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose—the more things change, the more they stay the same.

The lighted sign and neon trim outside the Bluebird were especially impressive to me, as I had just been working with Hugh Syme on the logo for my online cooking department, Bubba’s Bar ’n’ Grill. So around that time I was looking at vintage restaurant signs with new eyes. As I stepped out of the Bluebird, into the long slow twilight of June in the mountains, I noticed the neon bluebirds that decorated the underside of the entrance.

Strolling along Main Street, and across the tree-shaded lawns around the temple, I looked along the storefronts, mostly dark in the evening but for the brightly-lighted beacon of the Bluebird. I imagined all of the businesses my alter-ego Bubba could open there: right beside Bubba’s Bar ’n’ Grill could be Bubba’s bookstore, then Bubba’s liquor store, Bubba’s groceries, Bubba’s Best Western, Bubba’s motorcycles and classic cars, Bubba’s gym and yoga studio, Bubba’s music store, Bubba’s outdoor shop (bicycles, cross-country skis, snowshoes, hiking boots, binoculars, bird books), Bubba’s bank, and Bubba’s farm equipment.

Back at the motel, I was soon asleep, dreaming of Bubbatown . . .

Rain came in overnight, and the morning downpour and gloomy light looked as though they would be staying for a while. After the “free breakfast” (getting better these days, I must say, offering fruit and hard-boiled eggs with the usual dry cereal and gooey pastries), I dressed in all my foul-weather gear—not only for the rain, but because where I was headed, to the higher elevations of Wyoming, overnight temperatures were down in the low 30s, and the days only creeping into the 50s. As I had learned the previous year (see “When the Road Ends”), in the higher-elevation areas, early June was still late winter.

I have often described the stately, meditative mood that riding in the rain can evoke. With diminished visibility from mist, rain, and splash-back off the pavement, especially through a wiperless faceshield, and uncertain traction on wet shiny pavement, you naturally choose a slower pace. I was away from the interstates now, following a winding two-lane into forested canyons, often meandering beside turbulent rivers bursting with snowmelt.

Wisps and shrouds of fog and cloud draped across the distant mountaintops, darker than the snowy peaks peering through behind them—the Salt River Range, and the Caribou Range. The ribbon of sodden pavement led me past ranches and forests, and through occasional small settlements, north to the busier town of Jackson, Wyoming, at over 6,000 feet now, in the valley called Jackson Hole. I had long been curious about that much-admired mountain town and its surroundings, and had heard stories about people who had settled there happily, but the teeming rain “dampened” my experience of it that day.

Turning off at Moose Junction, I entered Grand Teton National Park (in French “vulgar slang,” grand téton means, to put it politely, “big bust”—describing the shape of the mountains as they appeared to lonely trappers). I stopped at the visitor center, which was jammed with people, many of them on bus tours, and got my passport stamp. The road through the park was marked “Closed in Winter” (which again, can mean well into June in those parts), but the ranger lady told me it was open.

I set off into the rain again, catching glimpses of the high, rugged, snow-capped Tetons to the left, and to the right, sweeping sagebrush, meadows, and wetlands—sometimes dotted with small herds of elk, displaying the characteristic buff patch on the butts of their dark brown bodies. Just from passing through Grand Teton so briefly, I saw that it would make a great destination on its own—the park brochure showed the majestic scenery as it would appear on a brighter day, and there were plenty of interesting hiking opportunities.

But Yellowstone was still ahead, and not far now.

One common summer obstacle in high-mountain areas is road construction—repairing the damage left by harsh winters and violent thaws. Typically, one lane will be closed, sometimes for a considerable distance, and flaggers and pilot cars control the flow of traffic in one direction at a time. A few times I straddled the bike and waited in a line of RVs and cars, but was soon moving again—and climbing ever higher, into the 7,000-foot level now, and the snowdrifts were deep at the roadside and in the woods.

The ravages of the great forest fires of 1988 were visible around me, as in the above photograph, the hills spiked with young lodgepole pines and rotting trunks. In that dry summer of 1988, several smaller fires had swept out of control, then combined into larger firestorms, and burned for several months across the park’s nearly 3,500 square miles. As many as 9,000 firefighters, and 4,000 military personnel, battled the fire (incredibly, without loss of life), and the conflagration ended up devouring almost 750,000 acres.

However, perhaps the most important fact about Yellowstone National Park is that it is the oldest national park in the United States—founded in 1872—and thus the oldest national park in the world.

A writer I have long admired and often quoted, Wallace Stegner, wrote that national parks were “the best idea we ever had. Absolutely American, absolutely democratic, they reflect us at our best rather than our worst.” America’s only other comparable idea, perhaps, was philanthropy—another great invention that was unknown to wealthy Europeans (reluctant alms-givers at best, and their only “parks” were private hunting estates, where the entry fee for commoners was, oh, death). Europe had the Quakers to protest slavery, and the suffragettes to demand the vote for women, but the United States led the way in every cause you can think of where rich people helped poor people, willingly and generously. The roots of the word philanthropy are “love” and “mankind,” and the concept also reflected a “morality of wealth,” as expressed by perhaps the first and greatest of philanthropists, Andrew Carnegie: “To die rich is to die disgraced.”

National parks and philanthropy are certainly grand visions that speak eloquently of the magnanimity of America—its greatness of spirit. As agents for change, Americans set an example that the rest of the world, to a greater or lesser extent, has followed. We could always use more philanthropists, but today there are national parks in England, Tanzania, Switzerland, South Africa, Great Britain, Australia, Canada, and many other countries.

In the nineteenth century, when President Ulysses S. Grant signed the bill to establish Yellowstone National Park, the preservation of natural habitat and wildlife wasn’t yet a priority. Back then the intention was to preserve the unique thermal attractions—the geysers, hot springs, steaming mudholes, and fumaroles. The park is basically one big volcano, a collapsed caldera, and its active state is well demonstrated all over, even along the roadside.

By early afternoon I had entered the park, content to cruise along the wet road at the posted limit of 45 mph, between dense forests of lodgepole pine—which cover eighty percent of the park, the name describing the aboriginal use of their tall, straight trunks. The rain continued, but I was used to it by then, and just kept riding, sightseeing as much as I could, and pausing at occasional overlooks to spend more time taking in the views. Around the West Thumb Geyser Basin, plumes of steam gushed into the air, amid the unmistakable smell of sulfur (probably the origin of “yellowstone,” I’m guessing).

What looked like smoky fires along the shore of Yellowstone Lake were actually hot springs meeting the cold water and creating steam. The sulfurous, rotten-egg smell reminded me of a few other living volcanoes I had experienced—on Sicily, the Big Island of Hawaii, and especially, on the Caribbean island of Montserrat, just a few years before its volcano became seriously active, and destroyed most of the island. No wonder early humans associated the smell of sulfur (“brimstone”) with various devils.

Yellowstone Lake is the largest mountain lake (above 7,000 feet) in North America, and as I cruised along the northwest shore, I was surprised not to see any boats, even canoes. Later I learned from the park brochure that despite all the warnings about the park’s many other dangers, from bison, black and grizzly bears, thermal hotspots, and crashing into large animals on the roads, the most lethal activity in the park was probably boating—the water was so cold that if you fell in, you wouldn’t survive more than a few minutes.

In midafternoon I pulled under the wide portico in front of the Yellowstone Lake Hotel, a massive edifice of wooden siding painted in pale yellow with white trim. Originally built in 1891, it sported a few colonial-style add-ons from the 1920s, like the tall white columns on the façade. The hotel offered rooms in the main building, the large Annex, or separate little quarters they referred to as “frontier cabins.” Well, with plumbing and electricity, they were hardly primitive, and I always prefer those cozy, private kind of accommodations to being crammed into a big warren. Plus you can generally park in front of your door, making unloading and loading much easier. Soon I was parking my wet motorcycle in front of a little yellow cabin on Yellowstone Lake.

The phrase had an irresistible rhythm, like a song lyric (in iambic tetrameter, to be technical). I couldn’t imagine that line in any rock song, but it might work for a country singer—a Montana cowboy could escape his cheating woman by driving away in his pickup truck, then wind up drunk and broken-hearted, in a little yellow cabin on Yellowstone Lake.

Not too far north of that little yellow cabin on Yellowstone Lake, back in the fall of 1998, I had been hiking in Waterton Lakes National Park, in Alberta, and while pausing beside a waterfall, I noticed two birds perched above me. They inspired another unlikely line of iambic tetrameter, “Two gray jays in a lodgepole pine.”

After just over 1,000 miles of riding, it was great to feel myself slow down, as I carried in my luggage piece by piece, changed into walking-around clothes (and my rain jacket), and took a stroll around the grounds. I ducked through the rain, keeping to the shelter of the lodgepole pines when I could, noting many large “cow pies” (probably buffalo—properly bison—though I hadn’t seen any yet). Deep mounds of snow remained here and there in sheltered areas, and one resourceful traveler in a neighboring cabin had stuck six bottles of beer into one of them.

The nearby general store was a big old barn of a place, built in 1919, centered on an octagonal building of brown logs and shingles. It had an old soda fountain inside, and I took a stool and ordered a “Chicago-style” hot dog and a chocolate milkshake. Both were the best of their kind I had experienced in a long time.

The big yellow lodge itself was massive inside, the lobby open to a vast seating area of sofas and tables, with a bar and restaurant, souvenir shop, and tall windows looking out on the misty gray lake, the snow-dappled mountains beyond, and the overcast sky. The lodge was filled with enough people to be lively, but not to be crowded. The Lake Yellowstone Hotel is closed in winter, not opening until late May (the reason hinted at by those slowly melting snowdrifts still lingering on June 2), so I had made it there about as early in the season as possible.

All of which meant that it was still cold in those parts, and the weather forecast showed mornings in the low 30s, and the possibility of snow showers. My little yellow cabin was a cozy refuge in the night, and I took my time in the morning—walking up to the hotel in the rain to enjoy a full breakfast, then slowly climbing into my riding gear.

With only one day to tour around the park, before beginning the long ride back home, I wanted to see as much as I could. The day’s first goal was Old Faithful—apparently not so “faithful” these days, as each eruption can only be predicted by the previous one. Depending on its height and duration, the next eruption can be anything from one hour to two hours later. As I browsed in the visitor center bookstore and collected my passport stamp, I saw that the next eruption was predicted in about forty minutes, so I joined the crowd gathering in a circle around the boardwalk that represented the “safe area” (one nearby warning sign had been erected by a couple to the memory of their son, aged nine, who had been scalded to death by falling into a thermal hotspot). Under an intermittent drizzle, the crowd grew to several hundred, all eyes on a mound of clayey-looking sediment, from which a plume of steam emanated steadily, drifting away on the damp breeze. Every short belch of increased activity heightened the crowd’s anticipation, murmurs spreading and cameras raised, until at last the tower of white steam burst up, over 100 feet high, with a power and sound that were truly awe-inspiring.

Back on the rainy highway, I soon encountered another equally stirring sight—a large herd of bison crossing the road, blocking traffic in both directions while they made their leisurely way from one stretch of riverbank to another.

Earlier that morning I had encountered my first bison, feeding at the roadside, and I had turned around and nervously paused to take its photograph. Bison, like the African buffalo (one of the “big five” on African safaris, for their deadliness to humans, along with lion, rhino, leopard, and another unexpectedly homicidal animal, the hippo) are famously ill-tempered and unpredictable, and can weigh up to two tons, so as I straddled my motorcycle on the wet road, I felt a little vulnerable. Likewise in the above scene, for I was hemmed in by traffic and the bridge railings as the mother and her calf passed right alongside me, but without haste or paying me the slightest attention.

I knew I couldn’t expect to see much of Yellowstone National Park’s vastness in that one day, but all the same, despite the rain and cold, it was a pretty amazing day. A road circled the park’s interior, and a few signs along the way sketch a picture: Fountain Paint Pot, Firehole Lake, Steamboat Geyser, Obsidian Cliff, and Mammoth Hot Springs—an immense array of stepped travertine pools, sculptured circles brimming with steaming water and mud. From there I turned east, then south through a more open, prairie landscape and the lush green meadows framing the Yellowstone River, where I saw many more herds of bison, near and far, and occasional elk, feeding among the pines.

Unexpectedly, the star attraction to me was the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone, where two mighty waterfalls plunged in white sheets between jagged walls of yellow and red rock. I followed the spur road to the lookout points on the north side, parking to take in the incredible views, then again on the south side, which was even more spectacular, especially from the aptly-named Artist Point. On a U.S. Geological Survey expedition in 1871, the great landscape painter Thomas Moran had painted the Yellowstone Falls from a spot near there, and it had been his paintings, and William Henry Jackson’s photographs from the same expedition, that had helped to influence Congress to declare the area the world’s first national park the following year.

With my binoculars, I followed the angle of a birdwatcher’s powerful scope, and saw that it was trained on an osprey’s nest, a huge jumble of sticks perched on the pinnacle of an isolated crag. Two scruffy-looking chicks sat hunched against the chill and rain.

By the time I circled back to Yellowstone Lake, my eyes felt prickly with fatigue—overwhelmed by an excess of beauty (like the feeling I get in art museums, worn out after an hour or so of really looking). I stopped by the general store’s soda fountain for another bratwurst and chocolate shake, while I caught up on my notes and reviewed my photographs. Two of the employees, an elderly waitress and a white-haired old man at the cash register, recognized me from the day before, and both of them, separately, asked me if I was working around there—I wonder what I looked like to them? “Outdoorsy,” I guess.

It made me smile to think that apparently I looked, spoke, and acted like the kind of guy who would work in a national park. But after all, my first childhood ambition was to be a forest ranger—until I decided to become a professional birdwatcher, then a lighthouse keeper, then a history teacher. When it finally became clear that I couldn’t actually do anything else, they let me be the drummer . . .

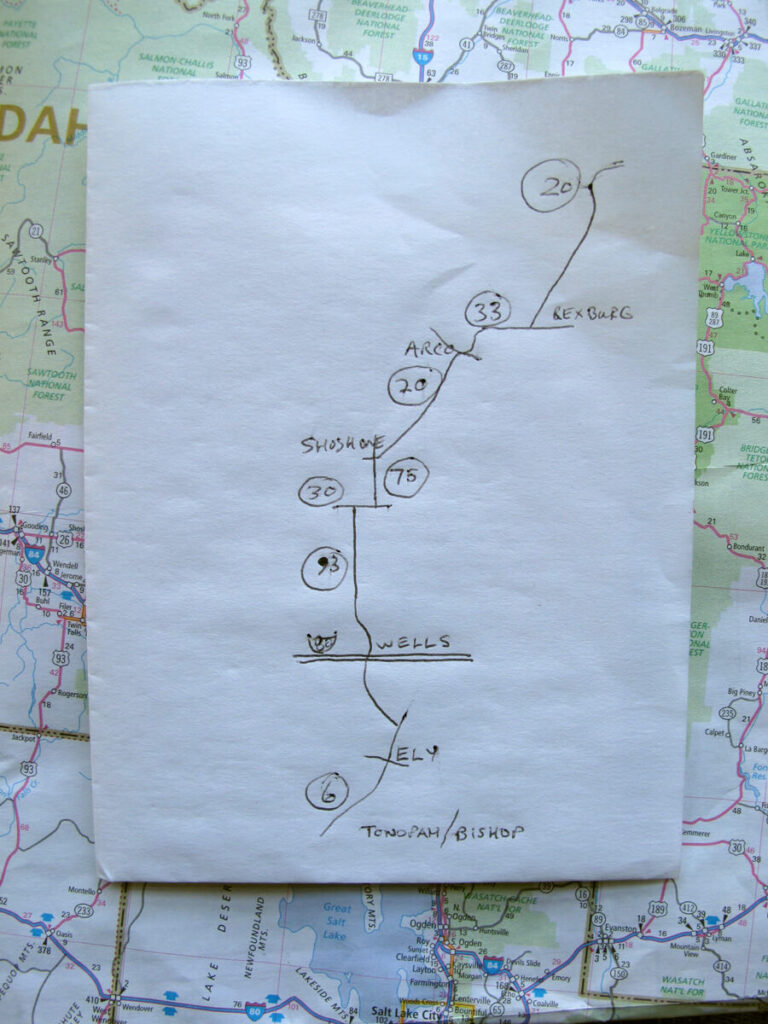

That night I got out the maps and charted my route home. My navigation tools were primitive, but effective—a paper map of the Western states, a blank sheet of paper from the typing tablet I always carry in my bike bags (as recounted in Ghost Rider, they started to become scarce with the decline of typewriters), and my Montblanc pen. I studied the map for a while, my finger tracing high desert roads, and eventually I nodded decisively—I would take a two-lane route home. Cutting down through Nevada, I should be able to make good time on those long, straight, empty roads. I drew a map of my route, showing the highway numbers, general directions, and town names (especially as refueling reminders, in that part of the country, where opportunities can be widely separated).

Once again, I was planning a marathon day—to get as close to home as I could, to make the following day more enjoyable (and so I wouldn’t arrive home exhausted; wives seem to hate it when you’ve been away and come back and you’re still no use!).

Fueled by a couple of muffins I had bought the night before, and the in-room coffee, I set out at 5:00 a.m., in the rain (I won’t mention that word again), with the temperature barely one degree above freezing. The sky was just beginning to pale, but the air was thick with moisture, often pooling in foggy banks in the valleys. Once again, the park’s 45 mph limit was just about right, with due regard for the wet pavement, limited visibility, and the possibility of large animals suddenly appearing in front of me, especially in the hours around dawn.

Following the Madison River to the West Entrance (glad to be taking a different way out, and see at least a little more), the sky began to clear, misty rays of sun cutting into the deep gorge. A pair of big bison ambled up the road toward me, and I decided it was wisest just to stop and wait, and try not to upset them.