Photo by Michael Mosbach

Ian Fleming’s James Bond novel You Only Live Twice takes its title from a haiku-style verse. “You only live twice/ Once when you are born/ And once when you look death in the face.”

As this man had just done. Finally I can tell about the worst crash I ever had—a “Now-It-Can-Be-Told” kind of story, after keeping it quiet for more than five years. Witness the biggest smile any camera has ever seen on this Bubba’s face, also reflecting Sir Winston Churchill’s statement, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.”

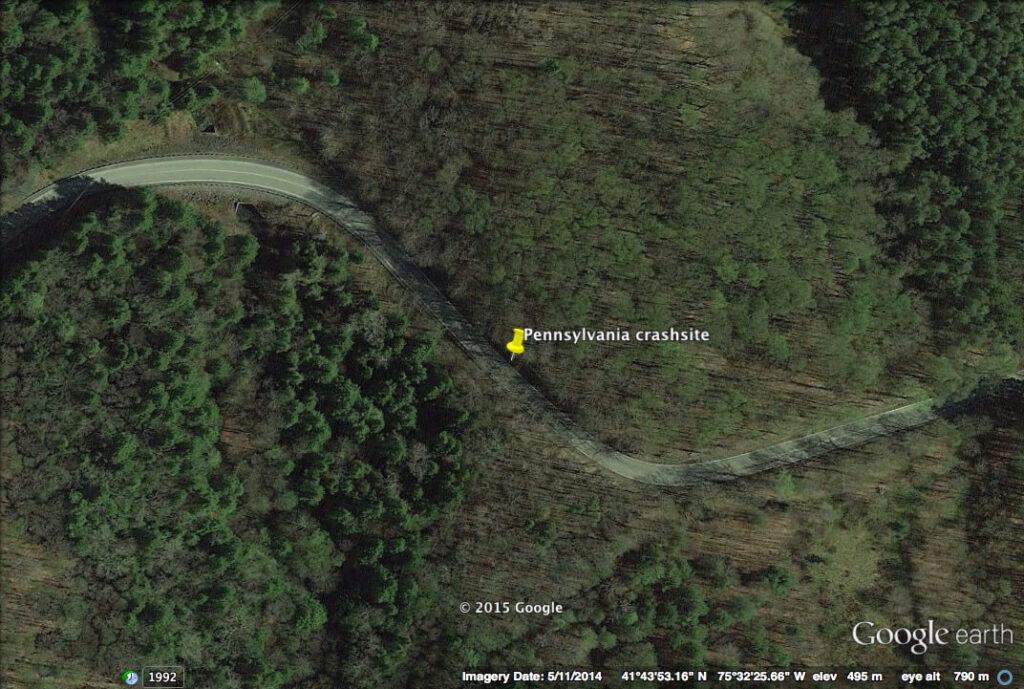

It was September 15, 2010, cool with mixed sun and clouds, a day off after a show in Boston on our Time Machine tour. Dave had dropped us in New York State near Albany, and in the morning Michael and I worked our way over to the Delaware River and started west across the backroads of northeastern Pennsylvania. We were riding in the general direction of the next show, in Pittsburgh, planning an overnight stop somewhere along the way.

The narrow paved two-lane wound along creeks and low ridges, through farmland and leafy woods, with many blind hills and corners. So our speed was “careful.” I came around a right turn to see a sharp left ahead, so was aligning the bike for that next corner entry, when suddenly the whole machine started shimmying below me. It oscillated side to side a few times, then went down. In a snap I was off and sliding across the pavement on my left side. What a universe of fear and helplessness opens inside you during split seconds like that. And no wonder time seems to slow, because it is so full—of raw, existential terror.

Michael came around that corner behind me to face a scene no riding partner ever wants to see—me curled in the fetal position in the ditch on the right side of the road, and my bike down on its right side a little farther on. Instantly alarmed, to put it mildly, Michael slowed and parked his bike across the road, where there was room. I got to my hands and knees, then stood up, seeing if everything “worked.” Then I stumbled down the roadside to hit the “kill” switch on the bike—still idling away on its side in the ditch.

If my first thought was about myself, and my second thought about the bike, my third thought was “What happened?” I looked up the sloping road behind me and saw a large rectangular patch of tar and gravel about five feet wide and twenty feet long. The patch and the loose gravel scattered from it took up most of the road, so there was no way I could have avoided it, even if I had been able to see it around the corner. Other passing vehicles had spread the gravel downhill on that lightly-traveled backroad, so my best guess was that it had been patched a few days before. It was a Wednesday, so maybe on the Friday afternoon a repair crew had decided that was “good enough,” and left it like that. Presumably there were no motorcyclists on that crew to notice how potentially deadly it was.

Ironically, though, even as the loose gravel knocked me down, it might have saved me from worse injury. As my body fell and slid along the pavement the gravel was like ball bearings, and later I noticed that even my plastic rain jacket wasn’t torn. Greater friction might have bent my limbs in different directions, making for more pain. Though on the other hand, that gravel meant I slid farther, carrying me closer to a roadside banked with limestone ledges and trees. Or there could have been a guardrail that would have brought me to a quick, painful stop.

The guardrail behind me in the first photo was at the next corner, where we could get both bikes safely off the road. Already I was imagining so many other possible outcomes to that grim moment—like the bike suddenly catching traction and pitching me across the road in what is called a “high-side,” maybe into the path of an oncoming truck.

So on balance I had been lucky. I would never deny that motorcycling is dangerous, and it even seems that way to me—“from a distance”—though not when I am doing it. Then I feel in “command and control” mode, as much master of my destiny as in any other situation. One longtime rider I read about spoke with wry wisdom, “If you love motorcycling enough, and you do it enough, it’s going to kill you. The trick is to survive long enough that something else kills you first.” To me that “trick” lies in being as safe and observant on the motorcycle as I can possibly be. The excitement and experience of motorcycling seem worth the risk—but a telling principle is that I would never encourage anyone else I cared about to take it up . . .

My armored suit, heavy boots and gloves, and full-face helmet all played their part in protecting me. (Imagine taking that fall and slide wearing running shoes, shorts, tanktop, and bandana—maybe mirrored shades for “eye protection”—the way too many riders in America dress. It might not kill you, but it sure would hurt—and the results would not be attractive.)

In any case, I was still well shook up, and a little battered about the ribs and hips, limping already. We noticed a scrape on the side of my helmet, so had to worry about concussion. I thought I was okay, but just in case Michael was checking on the location of the nearest hospital.

The poor motorcycle was an utter mess, the entire front section of fender and windscreen smashed away, and the right side luggage case and frame askew. The front brake reservoir was torn off, so I would not be riding that motorcycle away—which was good, because later it was discovered that both front and rear subframes were bent.

Michael got on the phone to Dave and asked him to come and pick us up. Without telling him exactly what had happened, Michael assured him “We’re okay.” Later Dave told me, “The way he said it I figured you’d gone down.”

With my wrecked GS only fit to be rolled on its wheels, Dave had to stop the bus and trailer across that whole turn to load it. Michael and I stood on the opposite hilltops holding T-shirts, ready to wave down and warn any oncoming drivers. (It says something about the road that, in midafternoon, there were none.)

With the wreckage in the trailer, Dave and I drove up the road to a nearby ski resort parking lot. Michael followed on his bike, then, in that safer spot, loaded it into the trailer. We drove south and west to Williamsport, Pennsylvania (“Billtown”), where Michael and I had often stopped in that part of the state. We took Dave to a restaurant we had enjoyed before, 33 East, and I limped my way inside. I was already worrying, “Hope I can play tomorrow.” After a good dinner (though I was conscious of Michael and Dave watching me for any suspicious symptoms of concussion), we slept on the bus near there. Talking to Carrie on the phone that night, I gave her a mild version of the events—just saying I’d had a crash, but was fine.

The following day we had to ride over 200 miles, much of it in the rain, to the arena in Pittsburgh. I was on the spare bike, of course, and was glad to feel I hadn’t been made fearful by the accident. Down deep I believed there was nothing I had done “wrong,” and that has always made all the difference to me. A Primary Principle in my definition of Roadcraft, “Whatever happens, it must never be my fault.” (Though I still wonder about the highway worker who walked away from that gravel patch thinking it was all right.)

Michael, Dave, and I agreed not to tell anyone else until after the Pittsburgh show—until I knew I could play. My journal note in all-caps advised myself: “PLEASE—TRY NOT TO TELL THIS STORY. FOR ALL GOOD REASONS.”

Because I knew I would want to write about it—for equally good reasons. Michael also chimed in and said I should never write about that crash. He shook his finger and said, “They’ll take away your fun license.”

We were both talking about, of all things, insurance—referring to the medical affidavit each band member had to sign to insure the tour against . . . any interruption to the flow of commerce. That affidavit included this question: “Do you participate in any hazardous activities or pastimes (e.g. motor racing, flying other than as a fare-paying passenger, hang-gliding etc.)?” The list did not yet include motorcycling, but I knew that actors, like keen motorcyclist Ewan McGregor, were not allowed to ride while filming. If news like this got out to the actuaries and “cover your ass” people, motorcycling might well be added to that “forbidden” list. I couldn’t imagine touring without motorcycling, but figured it was probably impossible without insurance, too.

So I kept it quiet and repaired the totaled motorcycle at my own expense. (It was only a few weeks before the South American tour, when I would need it for Brutus to ride, so there was a bit of worry there, too—I didn’t tell Brutus until later. Funny that Brutus now owns that motorcycle, Geezer IV, having bought it from me when I retired it.)

That night in Pittsburgh I got through the show okay, limping on and off stage but able to play “properly,” so that no one else would know. A few days later I shared the story with the Guys at Work, but still, for the next five years I kept my resolve never to write about that crash. Until the time might come when I no longer worried about anybody taking away my “fun license.”

(Even to the grocery store)

Photo by Juan D. Lopez