It has been six months since my last letter—and the time has been full. As ever, the more stories I have to tell, the less time I have to tell them.

I have never liked the clichés about time racing by, because I think you simply have to keep up with that pace—live your life at exactly the speed of time. Anyone asking “Where did the time go?” obviously wasn’t paying attention! Each day, week, month or year is a vessel of fixed capacity, to be filled with memorable incidents and stories. Every day can be observed in a way that is worth sharing—a motorcycle tour in South America or a trip to the grocery store and a pleasant few words with the baggers.

Responding to a letter from a friend who claimed to have nothing to tell, Thomas Jefferson wrote, “Just tell me about the events passing daily under your eyes.” Properly experienced and expressed, every life is of interest to another.

Now, at the pivot of another year (my sixtieth, I am proud to crow—how foolish to regret the passing years, if you consider the alternative), I am drawn to a kind of “reckoning,” a time to pause and reflect. The title phrase has long resonated for me that way: “the gate of the year.”

From the time I was small, I admired a framed piece of needlepoint that hung on my grandmother’s wall. She had made it on the family dairy farm in Southern Ontario during the dark days of World War II—when my father was a boy. On a field of white linen, her deft needle had stitched colored threads in a precise, artful design. In one corner, a brown-robed arm raised a golden lantern, and beside it meticulously sewn letters traced out a few lines of poetry that had been quoted by Britain’s King George VI in a December, 1939, radio address.

More recently, the historical importance of that speech was recreated as the climax of the 2010 film The King’s Speech, and it was the first royal Christmas Day radio broadcast in a tradition that continues with George VI’s daughter, Queen Elizabeth II. Her televised speech from Christmas Day 1997 was a key theme in another film, The Queen (2006), and resonated sorrowfully in my own life. Referring to the devastating fire at Windsor Castle, and the death of Princess Diana, she described it as an “annus horribilis,” disastrous or unfortunate year, and it had certainly been that for me.

Back in 1939, the king concluded his speech with the words, “I said to the man who stood at the gate of the year, ‘Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.’” He was quoting a poem by Marie Louise Haskins, which then goes off into some “celestial guide” sort of stuff (you know, putting your hand in the hand of the Judeo-Christian skygod). But the image of “The Gate of the Year” from grandma’s needlework has stayed with me all my life—especially as a time for reflection and resolution. Right now I have no idea what’s going to happen in 2012, or if I will “tread safely into the unknown,” but 2011 has been quite a year to look back upon.

(I am reminded that exactly twenty-five years ago, I sat down at the Gate of the Year and made a list entitled, “Why 1986 Was the Greatest Year.” Nice to think that even then I knew enough to count my blessings—and now I know it even better.)

Just a few days before the Pagan Winter Festival in 2011, amid all the haste and urgency of that season, I suddenly discovered that I had a wonderful gift before me—an unexpected few hours that I could afford to “squander.” Santa Bubba’s job was done: gifts chosen, wrapped, and shipped off to Canada, and Chef Bubba’s job was ahead: family feasts for Christmas Eve and Day. But that Wednesday afternoon I felt like I was miraculously facing an opening window—a breathing-space—and all at once I felt free, and I lit up inside.

Considering what I might do with that little wedge of freedom, a motorcycle ride would have been perfect, but my bike wasn’t “at home” just then. So I gathered my jacket, cap, and shades, and headed for the garage. Starting up my old Aston Martin DB5, just past its own 47th birthday, I let it idle out front for a little while. (Old cars, like old drummers, need careful warming up.) Then I climbed in and curved down through the canyon to the end of Sunset Boulevard, and turned north onto the Pacific Coast Highway. Accelerating hard to clear the carburetors (and for fun), I shifted up into third and fourth and into an easy cruise. The bright sunshine over the ocean and along the coastline was softened by a pale misty haze, and lazy waves tumbled onto the sand in long white rollers. Pelicans glided low over the water, fan palms speared up in motionless elegance, and traffic was light on a December afternoon.

Having grown up in Southern Ontario, where days in late December were typically cold and snowy, or filthy with slush, I have never taken California’s Mediterranean climate for granted. A permanent lesson was etched into my mind when I first moved there, in January, 2000, and was riding back from a motorcycle journey to Death Valley. Winding down through Malibu Canyon, framed in rocky walls and chaparral green after the winter rains, the Pacific glittered before me, and I thought, “It’s the last day of January. I’m on my motorcycle. And I live here.”

One piece of Roadcraft lore I try to pass along to younger musicians, athletes, or actors is that when you’re away from home for long periods of time, it is wise to make that home where your spouse wants to live. In 2000 I moved to California because that’s where Carrie was from, and where she wanted to live, and I knew my traveling days were probably not over. Fair enough. I maintained a foothold for my Canadian roots with a second home in Quebec—where I would love to have been spending a white Christmas, but . . . for now our home was California.

For a touring musician, the only proper destination in time off is home—the recently defined “staycation.” Toward the end of every tour, when people ask me where I am headed when the tour is over, I can only shrug and say, “Um, home?”

It’s like when people ask me before I go away if I am excited about going on tour, and I can only look at them in wonderment. Should I be excited about leaving my wife, my baby daughter, my friends, my dog, my house, my toys, my desk, my kitchen, my grocery stores, and all that?

Not long ago I read an interview with a young musician just back from his first tour, and he remarked that one lesson he had learned was that while he was away, his friends and family just went on with their lives—without him. He realized it was up to him to reconnect with them again, and try to rejoin their lives. I once defined that process for myself as, “Putting it all back together.” Meaning my life.

That morning had been my deadline for getting packages off to family members in Canada, and it ended a flurry of shopping, wrapping, and boxing. These days the American border paranoia complicates things terribly, and our assistant Adela spent three hours just filling out forms. Gift boxes coming the other way had been slower than usual to arrive, and I was stunned to see that some wrapped presents from Canada had actually been cut open. They were books!

Authorities are by nature cold and fearful, and one can see how they might feel they had to do that, but it still seemed sordid. (As it does when a Customs agent ruffles through your laundry.) And in the dozen years I had been celebrating my Pagan Winter Festivals in the United States, it had never happened before.

That long frontier between the U.S. and Canada was once proudly hailed as “the world’s longest undefended border.” That notion has become a sad joke, especially on the “Homeland Security” side: drones patroling the 49th parallel from the sky, ubiquitous surveillance cameras, long lines to enter on the roads from Canada, and . . . vandalized Christmas presents.

This impromptu tableau of ornaments and lights was created in front of the pagan tree during decorating time by Olivia, the owner of the darling little feet in the background. At almost two-and-a-half, this is the first Pagan Winter Festival she has truly experienced, and possibly the first one she may remember, now that she has passed what is called “childhood amnesia.” My own earliest memories start around that time, and in that season, so I would hope the same for her—and we tried hard to make this one unforgettable.

In recent years I have found the season to be difficult—because I used to love it so much, and the reasons I loved it so much had been taken from me. But now there was a new reason to love it again: for Olivia.

It is ironic that a religion that has historically co-opted prehistoric festivals for their own purposes would insist that pagans are unable to celebrate Christmas. Of course, it was ours first. The idea of grafting Christian festivals onto existing celebrations dates back at least to the 8th century, when Charlemagne massacred thousands of pagan Saxons for resisting his . . . “missionary zeal.”

It is also arrogant to suggest that without religion we have no reason to feel “goodwill toward men.” It isn’t fear of godly punishment or promise of heavenly reward that makes generosity feel good—it’s simple humanity. Any undamaged individual knows how good it can feel to help others.

I would love to avoid the taint of “faith-basher” I have been accused of, but a further irony is that the most fanatical “Christians” today are the most vocal against the biblical example of, say, being good Samaritans. They would proudly (and loudly) deny even mercy to the less fortunate.

(The shortest verse in the Holy Bible may yet remain the truest: “Jesus wept.”)

So the Pagan Winter Festival is mine, too, and my peaceful afternoon drive along the Pacific marked the brief nexus between getting all the presents out to people, and provisioning and preparing the feasts for Christmas Eve and Day. Once again, I had visited Bubba’s Bar ’n’ Grill to check my recipes, to refresh the knowledge and instructions from past experience, and make lists of necessary “ingrediments” (Brutus term). Shopping early for the non-perishables, able to scan the spice shelves for esoteric juniper berries and mustard seeds for the turkey brine, I had laid in most of the “grocerinos” (Brutus again).

So for that fleeting moment, I was feeling on top of the challenges ahead, and good about the year behind me.

Most recently, I had been recording in Toronto with my bandmates, from mid-October until early December. We completed the songwriting and arranging for the album, Clockwork Angels, we started back in late 2009—before going “on hiatus” for the Time Machine tour, and playing 81 shows in North America, South America, and Europe. (Some hiatus.) While Alex and Geddy were finishing the writing and arranging in one smaller room of the studio, over in the big room I was working with The Mighty Booujzhe, recording my drum parts. As we prepare to start mixing in the New Year, it is too early to say anything about the results. (I once described mixing as “the end of waiting,” while Geddy calls it, “the death of hope.”) About the process, though, I can’t resist spilling a little. It was our second time working with the production team of Nick “Booujzhe” Raskulinecz and engineer Rich “Tweak” Chycki. Beginning with a confident level of trust allowed us to reach higher, and I recorded my drum parts in a way that, for me, was completely different than ever before. Even right up to our previous album, Snakes and Arrows (2007), my method was to take a demo version Alex and Geddy had made of each song and play along with it many, many times. I would experiment with possible rhythms and decorations, and gradually organize them into an arrangement. At that point, I might start recording demos myself—often with Alex as engineer—and improve them over time, with input from my bandmates and coproducer (Booujzhe, in that case).

(A reminder about that nickname: Nick likes to suggest outrageous fills for me to play, and he will mime them with wild physical gestures and sound effects: “Bloppida-bloppida-batu-batu-whirrrrr-blop—booujzhe!” That last being the downbeat, with crash cymbal and bass drum.)

In recent years I have been working deliberately to become more improvisational on the drums, and these sessions were an opportunity to attempt that approach in the studio. I played through each song just a few times on my own, checking out patterns and fills that might work, then called in Booujzhe. He stood in the room with me, facing my drums, with a music stand and a single drumstick—he was my conductor, and I was his orchestra. (I later replaced that stick with a real baton.)

Rush songs tend to have complicated arrangements, with odd numbers of beats, bars, and measures all over the place, and our latest songs are no different (maybe worse—or better, depending). In the past, much of my preparation time would be spent just learning all that. I don’t like to count those parts, but rather play them enough that I begin to feel the changes in a musical way. Playing it through again and again, those elements became “the song.”

This time I handed that job over to Booujzhe. (And he loved it!) I would attack the drums, responding to his enthusiasm, and his suggestions between takes, and together we would hammer out the basic architecture of the part. His baton would conduct me into choruses, half-time bridges, and double-time outros and so on—so I didn’t have to worry about their durations. No counting, and no endless repetition. What a revelation! What a relief!

There was this one song, though . . .

Here the music stand in front of my drums represents an historic event: the first time I have ever used written notes—or at least numbers. There were two sections of one song that were ridiculously complicated, and I didn’t want to have to stop and learn them in my old way—I wanted to keep playing. So I wrote them down: one passage in which the rapid-fire snare accents went “4-2-4-2-3-2-4-2-3-2-1-y” (16th note push), and a series of staccato punches that went “1-3-1-5-1-4-1½.” (Not exactly one-and-a-half beats, I guess, but a reminder that the last punch was also the downbeat into the next section.)

By these methods, each song’s drum part was composed, arranged, performed, and recorded in just a few hours, rather than many days, as in the past. Also, each performance occurred only once, with magic—or lucky—moments from a few takes combined into one that was fresh and spontaneous. Now I can learn and reproduce that part, if desired, much as I did by the old process, but of course it’s not the same. I like to believe that a listener can sense when a player is on the edge of his seat, so to speak, playing with urgency, invention, and excitement. Sometimes the listener may share the player’s relief at having got safely back to “one.”

Performing to that level was the satisfying culmination of several years of ambition, pursued through studying with Peter Erskine, practicing faithfully for months with just high-hat and metronome as part of my preparation for playing the Buddy Rich tribute concert back in ’08, making “The Hockey Theme” in ’09, recording two new Rush songs, “Caravan” and “BU2B,” in early 2010, and—perhaps paramount in the sense of working toward a goal—playing all of those shows on the Time Machine tour in 2010 and ’11. Study, practice, experimentation, composition, and recording all reach their acme on the stage—nothing is more demanding than live performance, thus nothing does so much for my playing. (A fact about which I remain ambivalent, because until real-time holograms are possible, and accepted by audiences, it demands such long periods away from home.)

Photo by Craig M. Renwick

The year also had its share of tragedies, failures, and regrets. (Such different animals those be! Tragedies can be shared, but I have learned to keep my failures and regrets to myself. That is a deep kind of Roadcraft. Like our song, “Bravado,” about burning our wings if we fly too close to the sun—the price of trying hard is occasional failure.)

One true tragedy was the passing of my drum teacher and friend of twenty years, Freddie Gruber. Freddie was 84, and had lived life entirely by his own lights, so it was a natural time (alas), and his decline was mercifully brief. I am grateful that I was simply around during that time, to be able to be there, for Freddie and for his caregivers. In the patterns of my life, I could so easily have been away on tour, and thus Freddie’s passing might have become more than a tragedy—it might have been a “regret,” even a “failure.”

Over the years Freddie had become a close friend to Carrie as well, and when I was away on tour, they used to talk on the phone pretty well every night. When Carrie visited Freddie for the last time, she heard him say something I had heard, too. After telling one story or another from his long and active life, Freddie would nod and smile, and say, “I had quite a ride. I wish I could do it all again.”

I was struck by that statement, because I had never felt that way myself. To the contrary—as much as I enjoy my life, I remain glad I don’t have to do it all again. But I still appreciated that sentiment of Freddie’s, and as a tribute, wove it into one of our new songs, with one character reflecting on his life in that fashion.

Some days were dark

Some nights were bright

I wish that I could live it all again

Another philosopher named Fred—Nietzsche—said something similar, “‘Was that life?’ will I say to death. ‘Well! Once more!’”

I smiled at a comment mutual friend Rob Wallis posted the day after Freddie’s passing: “The world seems a little less interesting today.” That was a lovely way to put it, and the way I feel too. I miss him.

Photo by Joe Testa

In early November, more than two hundred of Freddie’s friends, including many former students, gathered for a Celebration of Life. Many stories were told, good music was played, and laughs were shared. Freddie would have approved. As I wrote in my obituary for him (something else I was grateful to be able to do), “He was smart, hip, warm, and funny, and although he kept himself insulated from the intrusions of what he called ‘straight life’—the ‘real world’—he was wise in its ways, always well informed, incisive, reflective, and caustic.”

Early that afternoon, I saw Ed Shaughnessy across the room, and went over to pay my respects. Drummer with the Tonight Show Orchestra for many years in the Johnny Carson era, Ed had played on the Buddy Rich tribute album I produced in the early ’90s. We chatted for a couple of minutes, then Ed said, “As a teacher myself, I have always wondered, what exactly did Freddie do? I asked Steve Smith, and he just said, ‘It’s complicated.’ I asked Dave Weckl, and he said, ‘It’s complicated.’ Then I asked Freddie himself, and he said, ‘It’s complicated.’”

We laughed, and I told him he had given me an idea for what I would say to the people that day. For I was determined to make myself get up and say a few words, although public speaking is always . . . challenging for me. (“Terrifying” might not be too strong a word.) Also, for the first time I would try improvising that, too. My few previous attempts at formal public speaking, in front of audiences and television cameras, had been carefully composed, largely memorized, but also depended on a written script. When the band was inducted into the Canadian Songwriters Hall of Fame a few years ago, I volunteered to say a few words—and only found out later that they expected the speech to be “as bilingual as possible.” Yikes! My French reading skills were up to, say, the comic-book level (Tintin books a favorite), but I was very unpracticed at speaking the language.

The day before the event, in Toronto, I spent several hours with a local French teacher, polishing up my phrasing and pronunciation, and on the night, I also had the benefit of a teleprompter at the back of the room. It came off okay; but it was hard. The same was true at Freddie’s event, but I hope I was able to share a few insights into why Freddie truly was a legendary teacher, to those of us fortunate enough to have been “cultivated” by him.

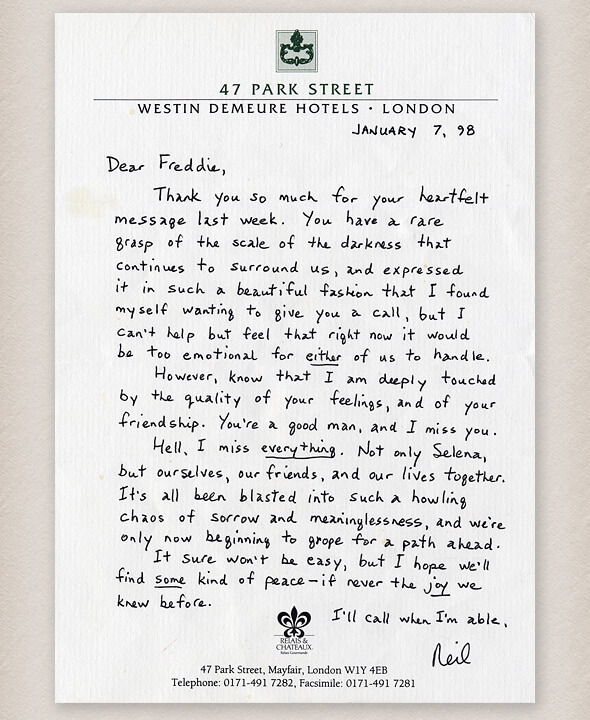

After Freddie’s passing, his longtime friend and trustee Edythe Bronston was clearing out his safety deposit box, and found this letter from me to him. I had written it during my “exile” in England in January 1998, with my late wife Jackie, after the death of our daughter Selena in August, 1997. The letter was written at the darkest point of my life—though I didn’t know then that just a week or two later, we would get the diagnosis about Jackie’s terminal cancer. So I was between deaths, as it were. (The gate of that year opened on a prison cell—what seemed to be an eternal sentence of grief, confusion, and emptiness. There was no light.)

I am especially touched that Freddie valued this letter enough to keep it carefully locked away all those years.

Another loss to the world in 2011 was the Anglo-American writer, Christopher Hitchens. He died young, at 62, of esophagal cancer—which also claimed my friend Ian Wallace a few years ago. Though I didn’t know Mr. Hitchens, I greatly admired his powerful mind and graceful writing. A quote of his reflects on some of the same topics we have been discussing here: of faith, using one’s time, and facing life’s blessings and tragedies with grace and gratitude:

The only position that leaves me with no cognitive dissonance is atheism. It is not a creed. Death is certain, replacing both the siren-song of Paradise and the dread of Hell. Life on this earth, with all its mystery and beauty and pain, is then to be lived far more intensely: we stumble and get up, we are sad, confident, insecure, feel loneliness and joy and love. There is nothing more; but I want nothing more.

Even writing close to his own end, as he did for Vanity Fair magazine, where so many of his trenchant essays were published over the years (their obituary described him as “incomparable critic, masterful rhetorician, fiery wit, and fearless bon vivant”), Christopher Hitchens maintained that integrity.

If the highest gift art can offer is inspiration, then encouragement is not far behind. Mr. Hitchens has made me braver—for good or ill—about speaking my own mind. No one expects to change anyone’s beliefs, though as Hitchens also said: “What can be asserted without evidence can also be dismissed without evidence.”

The inspiration comes from encouraging others to hold up the flag of reason—not just against the “believers,” but against those who use that faith for power. The earlier-described religious zealots like to claim that Thomas Jefferson and the other founding fathers intended to establish a Christian nation. Here’s what the great man actually said.

Shake off all the fears of servile prejudices, under which weak minds are servilely crouched. Fix reason firmly in her seat, and call on her tribunal for every fact, every opinion. Question with boldness even the existence of a God; because, if there be one, he must more approve of the homage of reason than that of blindfolded fear.

To “question with boldness” is not the same as to preach or deny. Likewise, to number one’s accomplishments is not the same as bragging. (Baseball player and commentator Dizzy Dean: “It ain’t braggin’ if you can back it up.”) I once heard some popstar diva asked about something to do with the “price of fame,” and she paused and said carefully, “Well . . . I mustn’t seem to be complaining.”

In the same breath, neither must one seem to be bragging (unless you’re a rapper, I suppose). So in reference to the actions I feel good about this year, I’ll only cite my adherence to another piece of worthwhile advice: “If you do well, try to do good.”

I have done well, and I have tried to do good. I know that a few times I have improved the lives of both strangers and loved ones—and by deliberate acts, not just being “cool by example,” or anything effortless like that.

So . . . thus have I arrived at my sixtieth year, more-or-less gracefully and gratefully, feeling healthy and strong, and feeling that I am putting words together and hitting things with sticks better than ever. (Though it’s worth noting that I trained for two months to be in good drumming shape for those sessions. The passing years do demand more attention to fitness and stamina.) Now I have the reward of listening to the drum parts I have performed for this album, and recognizing with quiet satisfaction that I am working at a whole new level of both funky, dirty, greasy groove and fancy show-off technique—a combination I have been seeking my entire drumming life.

And if I have shone a little light into the lives of others this year, often enough I have felt that light reflected back, in gratitude and goodwill.

“I said to the man who stood at the Gate of the Year, ‘Give me a light that I may tread safely into the unknown.’”

Seems to me you have to bring that light yourself.