The setting of this photograph is Death Valley National Park, California, near the site called Natural Bridge. The snow-topped Panamint Mountains form the backdrop, while I am gesticulating and (no doubt) pontificating in the middle, surrounded by the people and cameras of the Hudson Music crew. The subject of my little speech was drumming—specifically, drumming in front of an audience.

So that explains the title, but suggests a number of other questions. Starting with, I suppose, “Um . . . why?”

Well, it started in 1995, when I made an instructional video about composing drum parts and recording them, called A Work in Progress. My collaborators on that project were Paul Siegel and Rob Wallis, and we had enjoyed working together, sharing our ideas and realizing them on film. Paul and Rob were both drummers who had gravitated to the educational side, founding Drummer’s Collective in New York City, then later Hudson Music, to make instructional DVDs. They were around the same age as my bandmates and me, and likewise had enjoyed a long, productive partnership of close to the same duration, so we understood one another.

In 2005 the three of us made another instructional video (this time “straight to DVD”), Anatomy of a Drum Solo, which investigated the title subject, based around my solo from the R30 Tour. That solo had been filmed and recorded in Frankfurt, Germany, and thus was titled “Der Trommler” (the drummer). (On Rush in Rio, it was “O Baterista!,” while the Snakes and Arrows version, filmed in Rotterdam, was “Die Slagwerker.”)

The theme for our next collaboration seemed obvious: live performance, preparing for it and surviving it. In early 2010 we began collecting material, now augmented by a new member of the Hudson Music team, Joe Bergamini. “Jobee” is a well-schooled drummer in several fields, as well as an educator and journalist, and has been particularly successful in the orchestra pits of Broadway—first-call drummer for many of the hit shows, including such richly percussive and challenging scores as In The Heights (I loved that show). Jobee has a frighteningly detailed knowledge of my work, my methods and influences, and thus his inputs and questions were insightful and inspiring.

In April, 2010, the Hudson Music crew joined me at Drum Channel in Oxnard, California, and filmed several days of my rehearsals for the Time Machine tour. In July they filmed an entire Rush show, in Saratoga Springs, New York, with supplementary “drum-cams” on me. They also captured the soundcheck and pre-show warmup, when I did a bit of talking to the camera, as I had during the Drum Channel filming in April. However, we would need to shoot some more “talkie bits” to go before each of the songs from the live show, explaining about special problems or challenges in a particular song, and technical highlights.

So, I thought, why not go somewhere really nice to shoot those?

A Work in Progress had been filmed in May of 1996 at Bearsville Studios, in New York’s Catskill Mountains, so we had plenty of nice outdoor settings for the narrations around the neighboring woods and lakes. Same with Anatomy of a Drum Solo, which was shot at nearby Allaire Studios in the summer of 2005.

This filming session was scheduled for January, 2011, so we were limited in choices for outdoor shooting. Winter in Quebec might have been pretty, or not—you can never tell about winter weather. We might get bright, clear days with glittering snow mounded all around, or we might get gray skies and gloomy rain. I thought of Big Sur, a rugged stretch of California’s Pacific coast with dramatic ocean views among redwood forests and state parks and beaches. It was one of my favorite parts of the world, but at that time of year we might be interrupted by rain there, too.

So . . . I suggested Death Valley. Being the driest place in North America, averaging less than two inches of rain a year—and sometimes none—the chances of clear weather were good. I have been enchanted by that region of desolate splendor since my first visit, in the fall of 1996, when Brutus and I rode in under a full moon on what remains one of the great motorcycle rides of my life. (See “December in Death Valley.”)

I returned many times after that, notably on the Ghost Rider journey in 1998 and ’99, and every year or two since, so I had explored the area pretty thoroughly. The better I came to know it, the more I loved it.

It seemed to me that if we could combine such splendid natural backgrounds with the existing rehearsal and stage footage, it would elevate the show enormously. I was glad when the Hudson Music guys agreed, and set about getting the necessary permits (filming in a national park has certain “conditions”), and making the arrangements. Here I am riding toward Death Valley on January 10, on my way to meet the Hudson crew at Furnace Creek.

I am riding through the Panamint Valley, on the western side of the Panamint Mountains. The opposite, eastern aspect of that range is shown in the background of the opening photograph. From both views, the highest, snowiest summit is Telescope Peak (11,043 feet), which was the climactic setting in Ghost Rider. Its neighbor just to the north, Wildrose Peak (9,064 feet), was featured in the “December in Death Valley” story. That day my hike up Wildrose had led me into snow in the higher elevations, and so it was as I came riding in this time. Not long after the above photo was taken, the road veered left and led northeast into the Panamints, and I began ascending the little-used road toward the Wildrose Pass. The narrow, winding track got rougher all the way, the pavement often crumbling into gravel as it twisted steeply upward.

Then, as I rounded a bend, a sheet of white lay ahead of me in a shadowy canyon, a north-facing curve covered with snow. Where a few four-wheelers had slithered through, their tracks were compacted into slick ice. I stopped right there, and carefully turned my bike around to head back down. I might be able to tiptoe through that one icy stretch, but there would likely be more snow higher up, and I was alone. People were waiting for me, expensively. It was no time to take silly risks.

Once safely turned around, I straddled the bike at the edge of the snow, watching as a four-by-four pickup eased up and stopped beside me. The driver lowered his window, and we greeted each other. I told him I was heading back down, and he said, “Maybe I’ll try it a little farther.” But when he went to accelerate upward, all four tires started spinning, “zing, zing.”

I smiled and said, “Maybe not.”

He chuckled and nodded agreement, “Maybe not.” He reversed carefully down the road until he could turn around.

I followed his truck down through the rough part of the road, then passed him with a wave as the pavement smoothed out. Now I would have to take the longer, but more well-traveled and lower-elevation route over Townes Pass—which was fine, but with that unexpected dead-end detour, and no gas until Stovepipe Wells, I would have to stop and pour in the extra gallon of gas I carried on the back of my bike.

When I had loaded the bike the previous day, I had almost decided to leave that accessory behind. I felt I knew where all the gas stations were around Death Valley, and how to plan my stops, so I shouldn’t have any problem.

However, the “Roadcraft” lesson would be that sometimes you encounter . . . the unexpected. So you’d better be ready.

The next morning I was waiting at Furnace Creek when Rob, Paul, and Jobee arrived with their crew—director Greg McKean and cameramen Dan Welch, Jeff Turick, and Nate Blair. They had all flown into Las Vegas, and drove up in a rented Suburban and Ford sedan, carrying a ton of camera gear and plentiful snacks for the perpetually peckish Jobee. Over an intensely action-packed day and a half we filmed my “talkie bits,” prompted by Jobee’s questions, in six or seven spectacular locations. I also encouraged them to capture some “gratuitous riding footage,” as I hoped to bring as much variety to this drumming DVD as I could.

My dream would be to create a show that even non-drummers would enjoy watching, and now, thinking ahead to the coming months, it will be exciting to see all of those parts, from the rehearsal studio, the live stage, and Death Valley, edited together into what we hope will be an entertaining and instructive program. The working title is Taking Center Stage: A Lifetime of Live Performance.

This story will return to Death Valley and the film shoot directly, but I have to explain that even while I was engaged with that adventure, another big project was filling my days—a new book. I have long wanted the stories I write for this department to be “dignified” and made permanent by appearing in print, and at last I made it happen.

Typically, it turned out to be a much bigger job than I anticipated, but—everything does, if you aim high enough. Once I had found a publisher and stipulated that the book had to be in print before the tour’s continuation in late March, they gave me a list of requirements:

I needed a title and subtitle, which would help direct the design of a cover, which I would develop with Hugh Syme, as usual. I would have to write a new introduction and afterword, supervise various copy elements for the jacket and flaps, choose photographs for them, find all the text and photograph files for each of the twenty-two stories, then read over the copyedited text, the typeset text, and finally the corrected text. All in all, it was a solid two months of work, but I was delighted to see it truly coming together—a collection of stories that had been written and published independently now took on a unity, a single narrative span, that covered almost four years of my life. At first I had been daunted by having to write the “Intro” and “Outro,” but they proved to be the keystones in framing the twenty-two individual stories, to make it feel like one.

During that process of putting it all together, it occurred to me that there are few activities more enjoyable than making things. When I was young, it was car models, go-karts, then later pop-art mobiles and laughably inept carpentry. A couple of years ago I ran across a wall-mount “drumstick holder” I had dreamed up in my teens. It had been inspired by my dad’s cue rack by his pool table, but it was a crudely shaped assemblage of gray-painted plywood, with holes drilled by an old brace-and-bit—it looked like it had been crafted by a troglodyte. But still—I had made something.

It is stimulating and satisfying to write stories, or play the drums, but most gratifying of all to me is creating a physical object: a book, a CD, a DVD. Of course it remains the content that gives the mere object its value, but many would agree, I hope, that owning such a carefully-crafted object is more pleasing than just acquiring the content by whatever means. That urge may sustain the existence of things apart from their content, and that would be good, methinks.

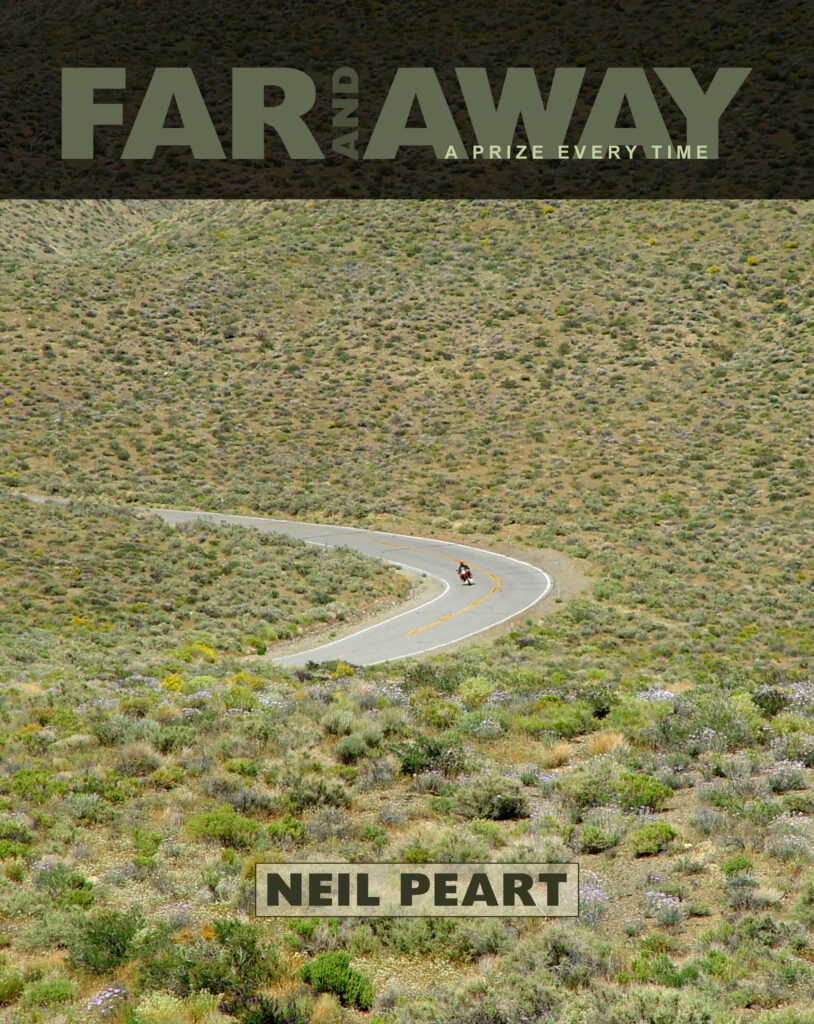

The cover photograph I chose was taken by our Master of All Things Creative, Greg Russell, while he and I were riding together in Central California in 2008, on the Snakes and Arrows tour. The setting is the Westgard Pass, between Nevada and California, and at the time of using the photograph in a story called “South by Southwest,” I remarked that it was the kind of spacious photo you didn’t often see in motorcycling magazines. (They tend to focus on the hardware.) However, this panorama certainly captured an element of what I love about motorcycling, and nicely exemplified the title, and the subtitle.

The other big event around this cyber-space lately has been our appeal on behalf of the Chilean Red Cross in “The Power of Magical Thinking.” In a way, that episode led to the making of the book.

When I finished writing that story in November 2010, I was wondering if that might be the time to start trying to generate some revenue from these stories. Given the time and effort I spend on them, plus paying editor Paul McCarthy for his input, and Greg Russell for his design, not to mention manager Brutus over at Bubba’s Bar ’n’ Grill, I had been looking for a way to make the place more self-supporting. The excellent Bubba’s merch had not caught on as wildly as Brutus and I had hoped, and it had been hard for us to find a way to introduce advertising tastefully.

Greg, Brutus, and I tossed around ideas for selling the story, like maybe asking for a nominal charge of one dollar. Even if only some of the readers kicked in, it wouldn’t take much of a fraction. (With the eventual posting of that story in November, plus a new edition of Bubba’s Book Club, we set a new record of over 63,000 visitors—two million hits.)

That solution was defensible rationally, ethically, and even economically (on both sides), but it remained hard to feel good about—getting all uppity and demanding people start paying for what they had been getting for free. Oh, I knew it was the right thing to do, especially in terms of setting an example for others in the “Slow Blogging” fraternity—those who, like me, found the medium creative and rewarding in every way except for the minor detail of earning a little money. Back in the ’70s the clever English pop group 10CC had a song that went, “Art for art’s sake/ Money for God’s sake.” Or as my riding partner Michael likes to point out, “A girl’s gotta eat.”

Then I hit on the idea of making those contributions charitable, and the story itself pointed to a deserving recipient: the Chilean Red Cross. Greg designed a cool little appeal, in which we asked for a minimum donation of one dollar, with the option to skip straight to the story. Brutus coordinated the fund-raising, which was a surprisingly complicated undertaking. (As I have learned from observing Don Lombardi’s struggles in launching Drum Channel as an online resource for drummers, anyone who is truly interactive with the Interweb, even in the second decade of the twenty-first century, is still among the “pioneers” in that brave new world. As a consequence, obstacles and complications seem endless.)

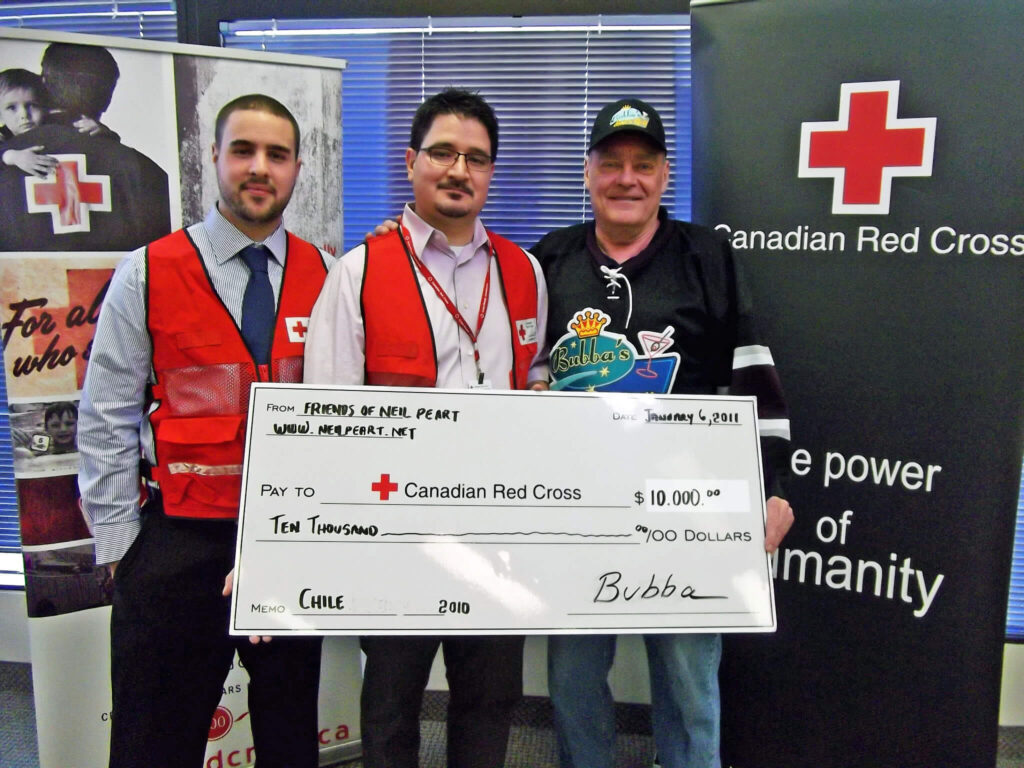

We managed to get it all “active” in early November, and by the time we closed the appeal in early January, a couple thousand people had willingly chipped in, many at more than the minimum. We had raised almost $5,000, and I decided to match that, so Brutus was able to pose with a “novelty check” (“cheque,” in Canada, which I think is a useful distinction, but it doesn’t “translate” into American) for $10,000.

photo Tracie Moore

So, a turning point of sorts had been reached, in my mind. Somehow the idea of having a story generate some income, even for charity, fired up my ever-growing wish to see those stories in print, as a published book. Thus was born the desire to create Far and Away: A Prize Every Time.

Some questions lingered, however. As I worked with the publishers to assemble and groom the stories for print, that edition was becoming the definitive one, with its more generous and asymmetrical layout, its larger format, and its sheer existence as a thing. Now the online versions felt like “demos,” and I really wanted to take them down, to have the book take their place, in every way. I decided to leave up the most recent year’s worth of stories. That way we would still offer a nice variety on the site, and it happened that those stories were all part of the same “chapter” of the larger tale.

Speaking of matters of scale, I call this photo “Death Valley bonsai,” because the skeletal, gnarled tree was actually only about a foot tall—a lovely example of the miniaturization of desert life (and death). The shot was taken near Badwater Basin, the lowest spot in North America, at 282 feet below sea level. It is also the hottest place in the Western Hemisphere, with a record temperature of 134°F in 1913.

It was nowhere near that hot on the days we filmed in Death Valley, however (the snow in higher elevations is a clue). The morning temperature was 37°, barely rising to 60 through the day.

The water in the background is another illusion. A recent rainfall had flowed down from the rocky canyons and alluvial fans, bajadas (the debris fields at the base of the mountains, eroded into perfect angles, called the “angle of repose”—Wallace Stegner used that as a metaphor in a fine novel with that title), and at the lowest point, an inch or two of water had collected over the usual white mineral flats. Desert landscapes are hard, impermeable surfaces, like natural concrete, with little vegetation, so any water from rain or snowmelt just goes hurtling downhill, carrying everything before it. That’s why flash floods are so dangerous in the desert. (Though they also fulfill a needed function in nature: certain seeds only germinate when their hulls are worn away by the stones carried in a flood, the water increasing their chances of survival.)

Our film crew set up right at the edge of the shallow lake, where director Greg wanted to capture the mountains reflected on the water behind me. We all hiked down to the point cameraman Jeff had scouted, but the salt-crusted soil was sodden, and people’s boots started sinking—some to their ankles. Being posed at the very edge of the water, I had been given three two-by-fours to stand on, but as I watched cameraman Dan sinking before me, lamenting his “one pair of shoes,” I gave one of the boards to him.

“A flotation device,” I said.

The rest made do as well as they could, dancing and sloshing around to find firmer footing.

After I had introduced the setting on camera, Dan remarked that it was funny to hear me describe being in the lowest, hottest, and driest place in the Western Hemisphere, with a great big lake behind me. (Also, I know now I should have said lowest and driest in North America, because there’s a lower point in Argentina, and the Atacama Desert in Chile is drier. Live and learn.) Dan was right, and I redid the speech to explain the “lake.”

We had already shot segments in front of the Artist’s Palette and Natural Bridge, from Badwater and different views of Zabriskie Point, and of me riding past the sand dunes and along the valley floor. The final location I was hoping to get was Dante’s View, overlooking the length of the valley and distant mountains from 5,442 feet. The park ranger who had been assigned to “watch over us” (one of the conditions imposed by the national park) reported that the road up to that peerless viewpoint was presently closed due to snow. He said he could get us through the locked gate, but that only his four-by-four truck, and maybe the film crew’s Suburban, would make it to the top—not the Ford sedan, or my motorcycle. I was disappointed to hear that, as I had visions of filming my ascent on the bike, as a possible way to introduce the whole show—but, “it is what it is.” At least we could get up there some way.

Late in the afternoon of the second, final day, we headed for that location. Leaving Badwater, I told the guys I was going to gas up in Furnace Creek, then would meet them at the locked gate. But as I climbed that narrow, winding road (and as the temperature fell), no barrier appeared—until a natural one occurred, a belt of snow across a sheltered loop of road.

Knowing I had other people around to help pick up the bike (and/or me) if necessary, I decided to chance it. Slowly I crept along the road’s edge, where the snow was softest, with my feet down like outriggers. I made it through that stretch, but soon there was another one, this one even deeper and icier. Again, I tiptoed through, and ahead I saw the parking area for Dante’s View above the final set of steep, snowless loops.

But, there was no one else there. We had less than an hour of daylight left, as the sun descended toward the Panamint Mountains, so I felt anxious. We wouldn’t have another chance. What if the others were waiting for me farther down? I really didn’t want to ride down and find them, and have to traverse those snowy patches twice over, so I could only wait. It seemed such a long time, the orange sun inching ever downward, before I finally saw the ranger’s pickup, the Suburban, and the Ford making the ascent. They had been waiting for me lower down, some of them of little faith (Dan), sure I would never have made it through that snow.

It was a perfect moment for the Hollywood cliché, “People—we’re losing light!” Quickly we set up and filmed me riding down and up that last bunch of loops, with scattered snow in the scrub behind me, then set up at the viewpoint’s edge for my introduction to the program, in the kind of light photographers call “the magic hour.”

Now I would be racing the light in another way—to get downhill through the snowy patches and flooded washouts, with gravel strewn across the pavement, before dark. Even then, it would be another thirty miles or so back to the motel at Stovepipe Wells, in the chilly evening air, so I quickly put on all my cold-weather gear, and headed down.

Back on the main highway, I could relax, knowing it was an easy cruise now. Usually twilight is a scary time to be riding, with visibility fading for the rider and surrounding drivers, and wildlife more active. But there was little to fear on that road—clear vision on every side for many miles, and perhaps most important, NO DEER.

I paused at an overlook to watch the light fade across the valley, then rode on, cruising slowly, keeping warm, and feeling good now—looking forward to the Macallan waiting for me in my room.