Photo by Michael Mosbach

If motorcycling is science, traveling is art. Getting from one place to another independently, with a sense of adventure and appreciation, requires a creative vision, technical experience, and perhaps most of all, adaptability.

The high concept is, “What is the most excellent thing I can do today?”, but it must sometimes yield to realities like time and distance, weather and traffic, or even just getting to work on time. Because sometimes work is the most excellent thing I can do today, and I can only try to embellish the work with some recreation and exploration.

In artistic terms, adaptability is improvisation, a pursuit to which I have been dedicated musically for several years. Sometimes traveling has to be equally improvised — like when I draw a route on the map that appears “excellent” to me, but when Michael and I are “on the ground” that day, real-world elements like bad weather, rough roads, heavy traffic, or fading daylight may bring us to a point of decision. We pause and make other choices — on a day off maybe stop for the night sooner than I had planned, on a show day take a faster route to get to work earlier.

With the first show in Austin, and the second in Fort Lauderdale — a mere 1300 miles apart — I had two days off and the show day to get there, but still faced difficult choices. Between those two points, the most excellent overnight destination is certainly New Orleans, so I designed the first day as the “reward.” Dave parked us in Lake Charles, Louisiana (in what we have come to call “Château Walmart”), and in the morning we set out to meander around the southernmost backroads in the Louisiana bayous, Cajun country. (A sign I saw along the coast, “The Cajun Riviera.”)

The landscape was mainly flat grasslands, half-drowned and cut with manmade channels, most of the buildings built on high stilts. The surrounding area had been destroyed repeatedly by hurricanes, but kept springing up again, however reduced. Several shrimp and crab companies had processing plants, while large compounds housed service facilities for the offshore oilrigs, with ranks of helicopters lined up outside, and rugged-looked workboats and tugs tied along waterways. The sky was gray, the light flat, and we took no photographs that day. But there was one encounter I remember with pleasure — a small ferry across the Calcasieu Channel, near Cameron, Louisiana.

As the ferry pulled away on its short crossing, one of the workers offered me a “World’s Finest” chocolate bar — the kind often sold for local fundraisers. He had just bought them from a garbage truck driver crossing the other way, who was selling them for his daughter’s school. As I accepted with a smile, “Why, thank you!,” he said, “I bought five dollars worth,” then pointed to his coworker, a roundfaced young man with glasses, bangs and a friendly expression, “He bought fifteen dollars worth, and he’s already eaten three — in about five minutes!”

The young man smiled and nodded, while the first one continued, “When he finishes a cup of coffee,” he held up a thumb and forefinger two inches apart, “there’s still this much sugar in the bottom!”

The other smiled and nodded again.

“He likes his sugar with a little coffee in it!” We all laughed at the old joke.

Somehow being included in this friendly raillery between coworkers made me feel good — you know, “normal.” That is always a precious feeling in my highly abnormal life. And that very week two friends had remarked on how “normal” I was. I don’t get called that very often.

I loved this little excerpt from a note Dave Grohl sent to the three of us after the Hall of Fame show:

“Just when I thought life couldn’t get any weirder, I wind up in blonde bangs and white platform boots, playing my all-time favorite jam in front of my heroes. I would pitch a reality show, if I only lived in reality . . .”

After the reward of that day’s scenic ride, and arriving in New Orleans to a nice hotel and a fantastic dinner, we would pay the price — merging from downtown New Orleans onto Interstate 10 to ride over 800 miles of freeway, across Louisiana, Mississipi, Alabama, and down through Florida. It was worth it (barely), and spending two days living on “Planet Interstate” was good scientific research. The self-contained network of highways, gas stations, motels, and restaurants ends at the offramp — Cracker Barrel, Chili’s, Shell, Exxon, Motel 6 and Red Roof Inn — a closed world with everything the “express traveler” requires.

Photo by Michael Mosbach

Other days off were much more suited to the pursuit of excellence, adventure, and the art of travel.

After sleeping on the bus after the Fort Lauderdale show at another Château Walmart, Michael and I rode as deep as you can go into the Everglades, down to Flamingo, the remotest tip of the continental U.S. From there, we rode back up to the Tamiami Trail, the old east-west highway across Florida’s southern tip, before “Alligator Alley,” Interstate 75, was built.

Heading west to Sanibel Island for the night, we explored every sideroad, including a long unpaved loop through the most emblematic part, the watery cypress swamp, pictured above. After about four such explorations (scientific explorations) over the years, I have observed every part of the Everglades reachable by any kind of road. (Someday I will make time for one of the airboat tours.)

Crossing the vast sweeps of grassy savanna (the name Everglades derives from “river of grass”), the scrub forest of palmettos and pines, and those deepest, prettiest stretches of true swampland, cypresses and mangroves, the thought occurred to me, “Nothing is ever just one thing.” That seems a crude and slippery notion at the moment, I know, but I have hopes it will grow up into a Deep Thought.

I was thinking of people who hold only one impression of what these places mean: a mental picture of bayou country, the Everglades, the Great Plains, any desert, or any range of mountains. Even a forest — a coral reef. “Nothing is ever just one thing.”

Every time I visit an area like, say, Death Valley, or the mountains of North Carolina, I add pixels to the resolution and scope of my mental portrait of the world. (Reminds me of a geek T-shirt Michael loves, “I See Dead Pixels.”)

While riding slowly on a dusty track through watery swampland, I glimpsed a pair of eyes and a snout poking up from the brown water. I waved Michael to circle around and have a look, and sure enough, it was a “gator,” five or six feet long. Michael pointed out another one nearby, about the same size, and sighed dramatically, “I wish we had some kittens!”

Photo by Michael Mosbach

After Orlando, we had two days off before Nashville, and I started surveying the “Book of Dreams,” the road atlas, for possible areas of exploration. (Like interpreting dreams, maps can present confusing ciphers and vague symbols that require some “divination.”) As my eyes traced the red and gray lines, and considered the topography — gazing into the crystal ball of knowledge, curiosity, hope — I didn’t decide upon a route so much as a design was revealed to me.

Hard to explain — without years of experience at the sweet science of the art of travel — but the vision developed like this . . .

Run to the bus after the show, Michael pours me a drink, and Dave drives all night north to Atlanta. Unload the bikes and wind our way through the mountains of North Georgia (praised in “A Winter’s Tale of Summers Past”), into North Carolina and overnight at the Biltmore Mansion near Asheville. A morning meander around the Blue Ridge Mountains, and the obligatory transit of Deals Gap — a legendary stretch of U.S. Highway 129 in the corner of North Carolina and Tennessee which some promoter dubbed “the Tail of the Dragon,” boasting “318 turns in eleven miles.”

(A motorcycle journalist living in Florida described his state as having “eleven turns in 318 miles.” And most of those would be onramps! Yet Michael and I discovered what must be the curviest road in Florida, a little country lane west of Sebring that zigged and zagged merrily in ninety-degree turns (around old property lines, no doubt), and even included a stretch of gravel for variety. Like certain country roads in Iowa or Illinois, it had never been deemed “important” enough to be straightened by the bulldozers of “eminent domain.” On a warm Sunday morning, I was puzzled that we didn’t see one other rider, yet later on Florida’s Turnpike — certainly one of the least entertaining roads in the nation — long parades of cruisers, dozens together in glittering processions, rode toward us on their loud chrome chariots.)

Photo by Michael Mosbach

That same “Winter’s Tale” story described the sideshow-like atmosphere of Deals Gap in the summer of 2008, and I had hoped a weekday in late April might be “calmer.” But no. The parking lot around the little motel was jammed with cruisers in long shining rows, and a rally for Mini drivers (the BMW generation) drew hundreds of cars to the area, passing us in the other direction for hours.

Winding through its eleven miles that day, my main concern was the riders coming toward me — losing it, crossing the line, and taking me out. Typically Deals Gap sees many crashes, and several fatalities every year. A few sportbike riders on their race-replica machines were making crazy passes, going around slower bikes on blind curves, and we passed two fresh crash sites, where damaged bikes were being loaded onto flatbeds. The riders seemed okay (no ambulances) — probably just overcooked one of those 318 turns and slid off the road in what is called a “low side.” (A “high side,” where an out-of-control bike spits you off, is much more dangerous.) So I kept the pace conservative, with lots of space and time to maneuver.

Three separate photography companies were set up on different stretches, aiming cameras into the turns at each rider, with their internet addresses prominently displayed — you were expected to go online and purchase photos of yourself riding the Tail of the Dragon.

Trying to decide which was the most ill-suited vehicle on the road that day, I was torn between a Harley “trike” (needing the shoulders of Hercules to muscle around those corners), a step-through scooter (a “maxi-scooter,” but still), and the Harley in front of us with ape-hanger bars, the slow and wobbly rider wavering even more when he had to lower his left hand to wave by every following rider.

It was a circus, and its absurdity has only grown.

Thing is, though, that stretch of U.S. 129 is a beautiful piece of road, perfectly engineered in banking, immaculately paved, and combining a pleasing rhythm of tight turns. Having been mythologized, “fetishized,” by a certain subculture has been its ruin. (You might say the same about Sedona, Arizona, or Pigeon Forge, Tennessee.)

But never mind — even just in North Carolina, devotees of this sweet science can find many other roads that offer delights without de crowds.

Photo by Michael Mosbach

From there we rounded the Great Smoky Mountains to stop for the night in downtown Knoxville, Tennessee. Last fall we took a chance on a small old hotel there, the Oliver, and were impressed. It had been restored in a modern way that respected its past, and was part of the charming character of downtown Knoxville.

Which brings me to another area of scientific research that never ends: lodgings.

A capsule history of American hotels might begin with the railroads, then change abruptly with automobiles. Independent travelers did not need to stay in big cities, and gave rise to “motor courts,” “motor hotels,” and eventually, motels.

The archetype must be the grouping of small cabins with parking places, often nestled in trees or along a shore, but their disappearance was lamented as early as the 1950s by recent immigrant Vladimir Nabokov, in his unlikely classic, Lolita.

More space-efficient rows of rooms, with parking out front, became the classic motel. Now those in turn are disappearing, because people seem to prefer the “big box” variety of chain outlets. So these days, full circle, I am back to exploring downtown hotels — at least in small cities — that seem to be having a resurgence. The restaurants are definitely superior to the fare in Planet Interstate.

Littleton, New Hampshire, Knoxville, Tennessee, Bloomington, Indiana, Iowa City, Iowa — all worthy “hubs” for my travels.

Looking for interesting territory to explore between shows in Nashville and Raleigh, North Carolina, I wanted to cross Great Smoky Mountains National Park, and check out some more of those great North Carolina mountain roads. I picked a new destination for the night: Mount Airy, North Carolina. The birthplace of Andy Griffith, it was said to be the model for the fictional “Mayberry” — a connection upon which Mount Airy continues to thrive with nostalgic baby-boomers. “The Andy Griffith Show” was hugely popular in the early to mid-sixties, and continued in frequent reruns for years after.

The Mayberry Motor Inn was the quintessential clean, comfortable, convenient family motel, right across the road from Goober’s restaurant and Aunt Bea’s diner. (Should be “Aunt Bee’s,” of course — must be a copyright issue.) Out front was a mid-’60s Ford police car, with licence plate “BARNEYF,” and a ’50s pickup painted with Emmett’s Fixit Shop, the “filling station” where Gomer and Goober Pyle worked.

It was all like going back in time sixty years, and Michael and I both declared that stay the most relaxing night off we’d had all tour. In the morning we cruised the main street, passing large stores selling Mayberry and “Andy Griffith Show” memorabilia, and — inevitably — Floyd’s Barber Shop.

After Raleigh, heading up to Virginia Beach, we explored another side of North Carolina — the Outer Banks. Overnighting at the Château Walmart in Greenville, we rode down to catch the ferry from Cedar Island out to Ocracoke Island.

We pulled up at the ferry’s ticket booth, side by side on the bikes, and the attendant leaned out, an older, prim-looking lady with tightly-permed gray hair and rimless glasses. She said, “Are you traveling together?”

It should have been obvious, but it gave Michael an irresistible opportunity. “Oh yes — we’re on our honeymoon!”

Without a smile, she said, “O-o-okay,” and turned away. Not impressed.

Boarding the ferry, the crew told us it was pretty rough out there, and advised us to stay with the bikes — for the entire two-and-a-half-hour crossing.

Photo by Michael Mosbach

At least we had shelter from the wind and rain on the covered deck, and we were dressed warmly against the chill. I had been carrying around the previous Sunday’s New York Times Magazine, hoping for an opportunity to do the crossword puzzle — and here it was. I sat on the steel deck and worked on that, while Michael raised his hoodie and plugged in his iPod, grooving to the Moody Blues, To Our Children’s Children’s Children. (Michael is a generation younger than me, at least numerically, and I always laugh to see him “discovering” music I grew up with — recorded before he was born.) The sea was heaving steadily, especially when the ferry changed course, but the bikes remained stable.

Laughing about our encounter with the ticket lady, Michael scrawled “Just Married” in the dirt on the back of his luggage cases. I added a heart to dot the “i.”

That graffiti wouldn’t last long, however, as the rain would be with us for most of the next week, and soon dirtied up our bikes again. As rainy days followed one another in a damp parade, soon I was thinking of the quote from King Lear, “The rain it raineth every day.”

Early the following morning we had to make another fairly long ferry crossing, and only later did I reflect that our morning exemplified another facet of the art of travel. The journey comes first, not comfort or convenience, and you just keep going, whatever it takes. Without comment or complaint, without breakfast or even coffee, Michael and I got up early, loaded the bikes and set off into the rain. Fully three hours later we parked at a nice roadside diner around the delightfully-named Kill Devil Hills, near famed Kitty Hawk. We shed some of our wet gear on the chairs around us, and didn’t just enjoy, but very much appreciated a hot breakfast.

The show that night in Virginia Beach was outdoors, with the temperature in the 50s and a gusty, chilly wind. My bandmates, the crew, the string players, and the audience were all bundled up, and I hope they didn’t suffer too much. A drummer never needs to worry about generating his own heat. The wind affected me, though — several times when I tossed a stick in the air it was blown off course and out of reach — but that was a minor concern.

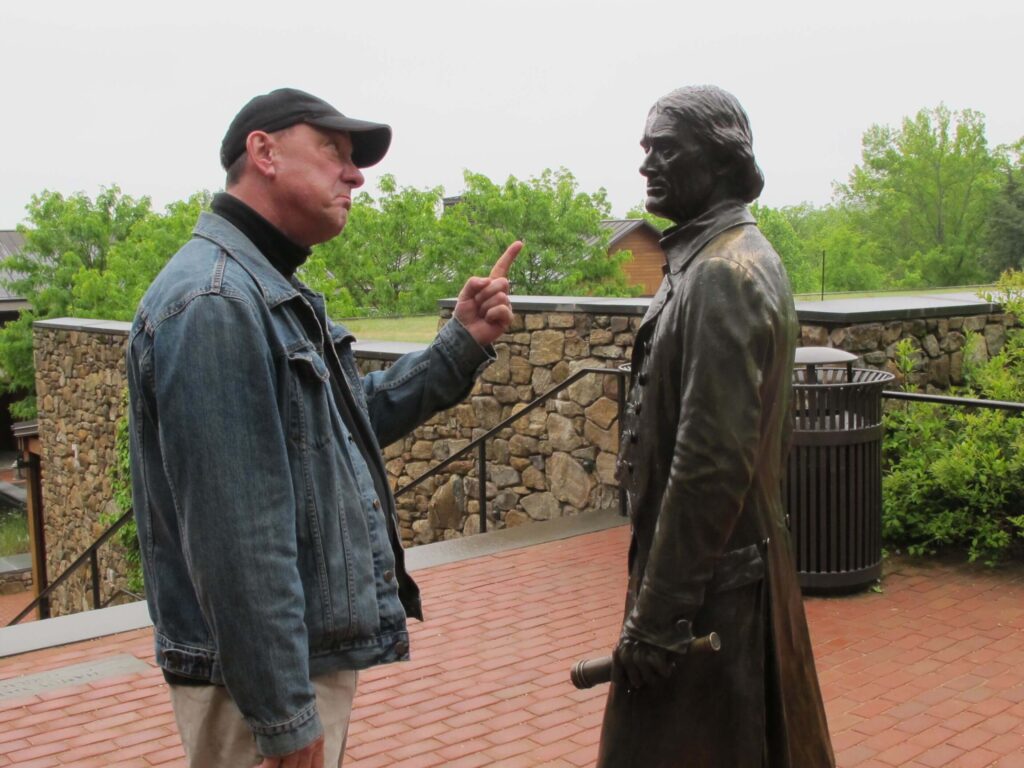

Looking over the map that afternoon for the upcoming rides, I was considering all the historical sites in Virginia, presidential residences and such. I asked Michael a fun question, “Who is your favorite founding father?”

I was thinking about Thomas Jefferson’s home in Monticello, which I had always wanted to visit. A few tours ago Michael and I had even stopped there, but it was a weekend morning in summer, and the jammed parking lot was enough to scare us off.

Michael agreed that Jefferson was pretty great, but also favored John Adams — his friend, enemy, then friend again. “Frenemies,” I said, “Like you and me!”

He put on a wounded expression, his lower lip trembling. “But we’re supposed to be on our honeymoon! I hate you!”

Then he lashed out with some pathetic profanity.

Bus driver Dave is an American history enthusiast, so he was glad to join us, and we had a guest rider, Richard Moore, a Toronto classical percussionist, versatile drummer, and fellow BMW GS rider. We slept on the bus at the Château Walmart in Charlottesville, then drove over to Monticello for a morning tour.

I had long admired Thomas Jefferson’s reverence for reading and reason, science and nature, and his quote, “I cannot live without books.” However, during the tour, as we stood in his library (I was surprised to see how small all the rooms were — but of course in the eighteenth century, heating was primitive), the guide informed us that although the great man had been devoted to books and reading, he did not like novels.

Well. Outside, I had to have a few words with the man about the power of fiction . . .

The rain held off during our Monticello tour, but poured down again as Michael, Richard, and I rode onward through the pretty Virginia countryside. Stopping overnight at the wonderful Homestead Inn, dating back to 1766, with portraits of all the American presidents who have visited — most of them, it seemed — we enjoyed a night of luxury and fine dining.

Next morning, Michael needed to get some service work done on his motorcycle, so took the “express route” toward the next show in Baltimore. Richard and I would also later face about 200 miles of rainy, miserable interstate, but first we were treated to a sublime morning ride — seventy miles of backroads in Virginia and West Virginia, in which we did not overtake one other vehicle, and only put our feet down for maybe three crossroads Stop signs. That’s pretty spectacular “freedom of the road.”

Oh sure, it was raining — check out the pavement awash on this West Virginia byway — but it was still beautiful. And sweetly scientific. Excellent practice for smooth technique.

Another sweet science would certainly have to be botany. A rose by any other name, et cetera. Down in the Everglades, I had been determined to get a shot of me riding by some mangroves. I pulled us over to the roadside and pointed to the scene I wanted Michael to capture, stressing the mangroves, and he said, “Um — what? The ‘manscapes?’”

Oh, he makes me laugh, but really doesn’t care about the names of things like I do. Same in the Blue Ridge and Great Smoky Mountains — I noticed that the “leaf line” was about 4,000 feet, and above that the trees were bare. The only green at higher elevations was the roadside grass and the evergreen rhododendrons in the understory. (Catawba rhododendrons, at that elevation, I learned later.) Michael gave me the same blank look when I told him to make sure he was getting the rhododendrons in the shot.

Throughout our northward progress up the East Coast, people’s yards were aglow with vivid pink and purple blossoms, fruit trees and lilacs. In the woods, I noticed sprays of white flowers on small trees among the greenery, and I wanted to know what they were. Like the redbuds in the spring of 2011 (see “Eastern Resurrection”), the more I noticed these flowering trees, the more curious I was to know their name. Eventually I stopped at the side of the road, walked over to one low-hanging branch, and picked a few of the flowers and finally identified them for sure — dogwoods. Michael was fascinated to learn that they were actually made up of white leaves, rather than petals.

(But no — he only sneered derisively and cast aspersions upon my masculinity. I fear our Michael is no natural scientist. And he’s certainly not sweet.)

Photo by Michael Mosbach

This sublime curve of empty road and surrounding woodland scenery were part of a day and a series of riding photographs that would astonish many Americans. Waking at the Château Walmart in Newburgh, New York, we rode south into New Jersey in the Delaware Water Gap area, and spent all day on scenic, lightly-traveled backroads. It was the only day without rain we had all week, and I think we collected more “keeper” photographs that day than any other — not least because I kept looking at different combinations of winding roads and early summer woods and thinking, “People wouldn’t believe this is New Jersey.”

It was all very far from the “Joysey” clichés of pop culture — “The Sopranos,” Springsteen, unscripted lowlifes, and a century of cheap jokes from New Yorkers. Our route meandered around for almost two hundred miles of pleasant riding, varying from rural two-lane highway with actual hills and curves to narrow strips of paving without painted lines, and even a stretch of rough dirt. I had tried to hit every dotted line on the map, which usually means unpaved (thinking of the theme “Every Dirt Road in Jersey”), but most of these were just badly paved — patchy and bumpy.

Photo by Michael Mosbach

We ended the day in Princeton — another addition to our list of favored smaller cities, often “college towns,” like Iowa City and Bloomington, Indiana, with quaint downtown hotels, plenty of restaurants of all kinds, and easy-in, easy-out convenience.

One more show to go — Atlantic City — and one more rainy day. I had mapped a ride down through the Pine Barrens region, a long stretch of dotted line through the Wharton State Forest, in the Pinelands National Reserve. We had ridden that way before, and knew it had some fairly challenging stretches of sandy gravel. So when the gray heavens opened once more and heavy rain pattered on our helmets and churned up the dirt road, I turned us around. “Know when to fold ’em.”

The dominant science that day was certainly meteorology, and its effect on physics, optics, and natural history ruled our day. The night, though, was ruled by the sweet science of music, and by people — our audience.

For our Hall of Fame speeches, the three of us chose “themes” that each of us would focus on — families for me, fans for Geddy, and for Alex, well . . . blah-blah-blah. (What a moment that was, when he hadn’t warned us what he was going to do. Geddy and I couldn’t see him “acting,” and thought he was going all Flavor Flav [no doubt that poor soul’s rambling, embarrassing, endless blather, under Chuck D’s stern, arms-folded scowl, will be trimmed for the broadcast]. Geddy muttered to me, “How can we make him stop?”, and I raised my heavy “trophy” behind Alex’s head as if to brain him. The two of us have long declared Our Lerxst to be “The Funniest Man Alive,” and of course his performance was a huge comedic success. But he should have warned us.)

Another special facet of the event (perfect jewel analogy) was to meet some artists I had long admired, and just knowing them, right away. Taylor Hawkins had been a friend for a few years (my bandmates appeared onstage with the Foo Fighters in Toronto, playing one of our songs with Taylor), but I had never met Dave Grohl, Tom Morello, or Chris Cornell.

When I traveled in China many years ago on a bicycle tour, I met another cyclist who had visited Tibet, and he told me about the greeting namaste. He defined it as, “I recognize the spirit within you.” It was like that with Dave, Tom, and Chris, appreciating and respecting their work, and them as artists of integrity. Meeting face to face for the first time, I felt I knew them — felt openness and trust, and saw it in their faces.

Perhaps less expectedly, I felt the same communion with Chuck D. Our music couldn’t be more different, but it seemed the spirit of it was the same. After the show, the three of us stood in a back hallway with him for a few minutes, and he told us a story.

“I grew up in Roosevelt, Long Island, near Nassau Coliseum. I had a friend who worked there, and one time I went to visit him, and you guys happened to be playing. I looked out through the doors at the audience, and saw like twenty thousand people completely focused on what you were doing. You were playing something quiet, and I said something about that dedication to my friend — and people in your audience ‘shushed’ me. That’s when I thought, I want to be part of something like that.”

Again, it comes back to appreciation not of us, but of our fans. (Whether we earn that or not is something else — but I know we try.) One reality that impressed me greatly that night was that not only had our fans clamored for years to get us inducted into that Hall of Fame (one of the directors joked that he didn’t know what he was going to do with all his free time now that he didn’t have to field the constant protests from Rush fans), but they took the time, trouble, and expense to be there. Right from the beginning of the show, everybody in the house knew that our fans ruled that place. That was pretty sweet. They were proud of us, and we were proud of them.

But, in “normal” life (there’s that word again), people can always keep you grounded, too.

In my pre-tour preparations in February and March, going to the Y three times a week for my fitness regime, one day I was on the cross-trainer, pumping through the endless cardio routine with grim determination. Exercise, for me, is an exercise of will. It may be science, but it is not sweet.

On the neighboring machine was a middle-aged lady, maybe a few years younger than me, with ear-buds in. At one point she pulled out one of her ear-buds and leaned over to say, “I’ve got a couple of male friends who are, like, total groupies for you!”

As usual, I was a little embarrassed to be suddenly “public,” jolted out of a far-off state of mind, so I just looked over, gave her a little smile and a nod, and kept pumping.

Then she said, confidingly, “But I won’t tell them!”

I nodded and smiled again, and said, “Thank you.”

A few more minutes passed, my arms and legs working in a rhythmic cycle, breathing deep and measured, mind wandering off on its own. I concentrated on my pace and heart rate, and watched the crawling timer.

Then she popped her ear-bud out again, and said,

“So — do you still drum at all?”