My first principle of art is, “Art is the telling of stories.” What might be called the First Amendment is, “Art must transcend its subject.” However, sometimes art’s natural subject—life—transcends even the mightiest attempt at conveying it.

Despite the love and respect I have for words, I know too well that there are occasions for which words are, alas, hopelessly inadequate. Even the combination of words and pictures, as I have worked into these stories for some years, has its limits. There are depths and heights of experience and emotion that the most accomplished arts of man only rarely capture.

Grief is one; joy is another.

But it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try. And a moment like the one above must be one more example—in two senses: in the surreality of the circumstances, and in my own failure to speak as eloquently as I wished I could. I tried, but . . . words failed.

It was the evening of April 11, 2012, at the Club Nokia in downtown Los Angeles. The occasion was the Revolver Magazine Golden Gods Awards, at which Rush was presented with the Ronnie James Dio Memorial Award for Lifetime Achievement.

Earlier in the year, we were asked about attending the ceremony in Los Angeles in April. The admirable Jack Black and his Tenacious D bandmate, Kyle Gass, said they would present the award, if at least one of us showed up to accept it. Geddy said he couldn’t be there because he would be in Japan, and I said I couldn’t be there . . . because I’m me.

Never comfortable amid crowds of people, especially if they’re making a fuss about me—plus facing up to public speaking, and public praise—I just feel tense and embarrassed. Anyone acquainted with me knows I try to avoid such situations whenever I can. (Of course it’s different when I am drumming—that is a more-or-less natural environment for me.)

So Alex manfully volunteered to appear on our behalf and accept the award. However, just days before, Alex had a personal situation at home in Toronto that wouldn’t allow him to travel to Los Angeles for the event. Discussing it all on the phone with our manager, Ray, he started to say, “I don’t suppose you would consider—”

I cut him off, “No possible way—are you serious? You know I don’t do that kind of thing. And it’s my moving day!”

That was true, but in the same breath that was saying “no,” my mind echoed with the true answer, “yes.”

Clearly I would have to do it, that’s all there was to it—it was the right thing to do. The only thing to do. Obstacles would have to be surmounted. Or ignored.

Alex felt terrible about disappointing everyone, and I felt a loyal obligation to bail him out. And besides, it would be too rude for none of us to show up. We are Canadians, after all.

So . . . the day my family moved from one overcrowded house where we had lived—and collected junk—for eight years, to another house that was soon overcrowded with boxes to be unpacked and organized, I had to duck into a shower that worked, find some decent clothes to wear (leather crew jacket from our Snakes and Arrows tour—the closest I have to “rock clothes”), and go say a few words that I hoped would be courteous, appreciative, and gracious.

Photo by Robert Knight

My longtime riding partner and security chief, Michael, picked me up at home, and distracted me with vicious banter on the way. (A friend once commented to Michael and me that she couldn’t believe how nastily we talked to each other. The two of us shared a look of disbelief. Nasty? We were insulting, base, crude, sarcastic, ironic, theatrical, gay, obscene, vicious, disgusting, and funny—but never nasty!)

We left the backstage parking lot and walked into a dark, crowded theater, and my senses were brutally assaulted. Strobing lights slashed and flashed in the darkness, and the air throbbed with noise from grinding guitars and double-bass pedals triggering samples (an insult upon the ears and sensibility of an old-school drummer). Flamboyant (an errant finger just coined a neologism: “Glamboyant”) rock people filled the hallways, and with head down to avoid being “noticed,” I glanced around in disbelief at a phantasmagoria of wild rock costumes, spiky black hair, and tribal makeup.

My brief presence did not include witnessing what must have been bizarre duets combining Johnny Depp and Marilyn Manson, or Dee Snider and the Black Veil Brides, but I saw and heard plenty. As my handlers and I shouldered our way through the backstage crowds, bright video lights illuminated rock veterans being interviewed in front of cameras—Gene Simmons here, Slash over there, and Alice Cooper that way. They were posed, arrayed, and lighted like figures in a wax museum.

I noticed their elaborate rock costumes—Alice in black leather pants with silver conchos, Gene in black leather pants and boots with intricate metal tooling—and I asked Michael, “Where do they get those clothes?”

Michael answered, “I hope you never find out.”

I suggested that there must be a store for them in Hollywood, and adopted a radio commercial voice: “Rock Clothes: for the Mature Male.”

He laughed and said, “There probably is a store like that.”

Standing amid all that with an almost dizzying sense of surreality, the stage manager told me which way to go up, and which way to come down. Jack Black inducted the band with his signature high-voltage School of Rock oration, then I was up there and holding a miniature Stonehenge (the award—shades of Spinal Tap) in front of blinding spotlights and a sea of youthful faces that seemed to be saying, “Who?”

I did my best to explain my presence and express my feelings, but alas, I fear words failed.

Later, for the magazine, I offered a more considered, written attempt:

I will start with raw honesty. (And why not?) It is the kind of thing that is “hard to know what to do with.” (No, ha ha, I don’t mean the actual award—Alex, Geddy, and I have long had a rule that all awards go straight to the office of our manager, Ray Danniels.)

Of course, I mean the honor.

On the one hand, it is wonderful to be appreciated, naturally. But on the other hand, you mustn’t let such appreciation affect you—mustn’t take it too seriously. Yet on the third hand (hey—I’m a drummer!), basic courtesy demands that you take it seriously enough to express proper gratitude for the respect and tribute it represents.

See what I mean? It’s complicated . . .

Such issues have never been a big problem for the three of us—simply because not much of that kind of thing came our way. For our nearly 38 years together, we have been fortunate enough to have had our loyal and enthusiastic audience (perhaps they should receive the lifetime achievement award), while the rest of the world was mostly oblivious—with a minor, if apoplectic, gallery of raging haters. So whenever an honor was offered to us, we would be surprised, and even a little suspicious:

“Are you sure?”

One quality that Alex, Geddy, and I share (among enough other points of agreement and humor to have kept us together for almost 38 years) is that we are always looking forward—in life, and in music. It is said that nostalgia isn’t what it used to be, though I would say that these days it is rather more than it used to be. But not for us. Even on our most recent Time Machine tour, in 2010-11, when part of the show included performing our 1980 Moving Pictures album in its entirety, there was no feeling of “going back” for us. Choosing that music, and performing it every night, was all about what that music meant to us now.

Sure, the old songs we continue to play in live shows are a part of our musical autobiography, but they are also simply a part of us. We liked them when we wrote them, and we like playing them now.

The Rush “mission statement” has always been clear: we make music we like, and hope other people will like it, too.

It also seems natural that we always feel strongest about our newest music—like the soon-to-be released Clockwork Angels album. Yet people will keep asking me, “What is your favorite Rush album?”

How terrible it would be if you had to answer with anything but your most recent work. To confess that your best work was past? Face that music?

Oh no.

The three of us, and the friends and collaborators around us, are very excited about Clockwork Angels. We modestly believe that it represents our best work on every level of our craft, and we sincerely (earnestly) hope other people will agree.

So, as I mentioned in my speech at the award presentation, our lifetimes aren’t over yet, and we hope our achievements aren’t either.

Now, in early 2012, we are poised to begin preparing to launch a major tour later this year, continuing into 2013. So we’ve got a lot of work to do.

We have to keep trying to deserve this award.

A few weeks later, the feelings that overwhelmed me at the Revolver event were amplified tenfold. The three of us met in Ottawa to be presented with the Governor-General’s Award for Lifetime Achievement in the Performing Arts. We shared the honor with several “real artists”—concert pianist Janina Fialkowska, dancer and choreographer Paul-André Fortier, theater director and stage designer Denis Marleau, filmmaker Deepa Mehta, political satirist and broadcaster Mary Walsh, theater director Des McAnuff, and a highly influential fundraiser for the arts, Earlaine Collins.

Earlier in the year, when the award was first offered to us, the stipulation was that all of us (yes, they stressed, all of us) would have to attend three days of celebratory events (two “black tie” and two “business attire”), and cooperate in the making of a short film in advance that would accompany the “gala night” finale.

Pegi in our office laughed at our very different replies to her first email on the subject—Geddy saying he would be glad to have another medal; Alex writing, “I accept, Your Majesty,” and yours truly wailing, “Three days of hoopla? No-o-o-o!”

However, as I almost always do, I acquiesced to the wishes of my bandmates, the Guys at Work. As I have said before in other circumstances—like to reluctant fathers with determinedly maternal wives—“When someone you love wants something really badly, you have to help them get it if you can.”

So I basically “surrendered.” When asked for a statement for the Canadian press, I offered this, with a similar ending trope:

As we put the finishing touches to what will be our twentieth studio album, Clockwork Angels, followed by a tour behind it this fall, we especially appreciate the presentation of this lifetime achievement award now—while we are still active. (Too active, our families might say!) Since our performance “lifetimes” aren’t quite over yet, this high honour is not just a reward; it is an inspiration. We will continue to try to earn it.

The celebration of the surreal began at Canada’s Parliament Buildings. With the other inductees, we were welcomed to the private office of the Speaker of the House, Andrew Scheer. He acts as an arbitrator in the House of Commons, and at a boyish thirty-two, he is the youngest Speaker in Canadian history. Moving down the hall to his dining room, we enjoyed a pleasant lunch, getting to know the others a little bit. Then we were all ushered to the House of Commons, for a Canadian Parliamentary ritual called Question Period.

We listened in on the astonishingly wide range of topics introduced—from the cost overruns on a new fighter jet (for the Canadian Air Force—so perhaps literally one fighter jet!), to the Newfoundland seal hunt, to an oil slick in the Pacific off British Columbia, to charges among the parties of corruption and slander.

Amid all that withering controversy, and sometimes heated tempers, we heard gratuitous references to Rush songs woven into the arguments, and one angry peroration on the city’s political machinations concluded with, “This is indeed . . . a villa strangiato.”

Another MP who seemed to be getting the worst of an argument suddenly spread his arms and looked up to the Speaker’s Gallery and shouted, “I would just like to say that Rush is here today! Welcome to our . . . parliamentary limelight!”

Later, our friend the Speaker (a child!) read each of the laureates’ names into the Parliamentary Record, and the Members rose and applauded us.

One disconcerting observation we shared was that it seemed the entire government of Canada was younger than us. Sure enough—the average age of Canadian Members of Parliament is fifty—nearly ten years younger. Many of them were in their twenties. Seriously, I ask you—how is it possible for politicians to be younger than rock musicians? (Though perhaps the better question is, “How can rock musicians be older than politicians?”)

(I think of P. J. O’Rourke’s quip, “Giving money and power to politicians is like giving whiskey and car keys to teenage boys.”)

Photo by Tom Sandler

The second day centered around a ceremony at Rideau Hall, the palatial residence of Canada’s Governors-General. Traditionally, they were representatives of the British Crown, but the role today is largely ceremonial—though acting as worthy, non-political ambassadors to Canadians and world leaders. (The day after our visit, Israeli president Shimon Peres was arriving to stay at Rideau Hall.)

Part of my attitude of “surrender” to those three days was that I hadn’t examined the program too carefully—I figured I would just go where and when I was told. Remembering back to when the three of us were given the Order of Canada in 1996 at Rideau Hall, there were no speeches, and I presumed anything we had to say would be part of the next night’s “gala” at the National Arts Centre.

Earlier that day I kept myself distracted by walking around Ottawa with my daughter Olivia, who, at two-and-a-half, was impressed by our capital city’s modest grandeur. It was a warm spring day, sky washed blue, trees and grass in fresh spring green, and beds of red and yellow tulips in full bloom. Olivia liked seeing the squirrels chasing each other, the Rideau Canal, the Chateau Laurier, a castle-like hotel, the glass paneled National Gallery, and the Houses of Parliament—dubbed by Olivia “The Castle of Canada.”

While enjoying that time with her, and carrying her back to the hotel on my shoulders when she got tired, I felt edgy inside, like on a show day, increasing as the afternoon departure neared. In the time leading up to those days, our women had made frequent comments about how “easy” it was for us guys, just having to wear a tuxedo or a suit. Maybe so, but they have never had to struggle with nervous fingers on tuxedo shirt studs and tiny buttonholes.

It was only when we met in the lobby that afternoon to depart that I learned the speeches were to be presented that day! Earlier we had agreed that instead of one of us taking on the responsibility, as I have done a few times, each of us would speak a short piece. Alex and Geddy had exchanged emails that afternoon about what each of us might say, but I had missed them all.

Words fail again!

I had thought I might spend some time the following day preparing a few remarks, and try to make them a little bilingual. The previous year, at a Songwriters’ Award show in Toronto, I had been very impressed by how smoothly nearly everyone had moved between English and French—not translating, but alternating remarks in our two official languages. It was very admirable, and seemed to represent Canada at its best, so I had been glad to face the challenge (faire face au défi) of doing that myself.

However, there was no way I could improvise in French, so I limited myself to remembering the proper formal greeting, “Your Excellencies, honoured guests, ladies and gentlemen,” then I said something about none of us laureates having arrived at that place alone. Or, spreading my arms back toward my bandmates, even just with a band.

I managed the opening okay, which seemed most important—and most likely to fail—and only vaguely remember what else I said. I mentioned how it had all started for me with my parents giving me drum lessons for my thirteenth birthday, and how they were “here today.” I talked about the contribution of those around us, like our office people and our road crews, and how our families were subjected to long and frequent absences. I closed with something about my bandmates of almost thirty-eight years, and passed the podium to Alex, then Geddy. They read briefly from their prepared notes (cheaters!), adding our thanks to our fans, and to the Canadian arts community. Later they both told me how nervous they had been, and it was nice to know I was not the only one.

At this moment on the following night, we were standing at the front of the mezzanine balcony of Ottawa’s National Arts Centre, in a row of the laureates and the Governor-General and his wife. We were looking and gesturing toward the stage, responding to a funny induction speech by another good friend, Matt Stone. Matt had generously traveled to Ottawa for the occasion, and the segment devoted to Rush included the South Park clip Matt and his partner Trey Parker had created for our Snakes and Arrows tour—the kids from the show performing “Tom Sawyer” as L’il Rush.

A short documentary had been put together for each laureate, shot by edgy young directors for Canada’s National Film Board. Ours mixed interviews with the three of us and a band of dedicated teenagers from Waterdown, Ontario, called Inner Volition. In the film’s final scene, Geddy said something about us still trying to improve in everything we do, and I laughed and added, “We are still trying to get better!”

After a perfect beat, Alex, sitting between Geddy and me, smiled and angled his thumbs outward at us, and said, “Well . . . they are.”

Genius.

Matt doubled it, as he talked about Rush and what we had meant to him in his youth. He said, “And they’re still trying to get better . . . except Alex!,” which got a good laugh.

Then the curtains drew wide to reveal a children’s choir, who sang “The Spirit of Radio” a capella. They were followed by a full symphony orchestra playing “Tom Sawyer.”

Once or twice Alex, Geddy, and I caught each other’s eye and just looked at each other. Delighted, of course, but . . . bemused might be the word. If words didn’t fail so epically.

The final performance in the gala was by Des McAnuff, a theater director and—evidently—would-be rock star. Backed by his Red Dirt Band, his film was a rock-video style performance of a lilting song with the refrain, “The Rain it Falleth Every Day” (quote from King Lear, appropriately, as Des was director of the Stratford Shakespeare Festival in Ontario).

Then Des and the band took the stage to play live, launching into a medley of songs from The Who’s Tommy. To the audience’s surprise and delight (though we knew about it before, confidentially), they were joined by the composer himself, Pete Townshend, the Godfather of Rock. Des and Pete had worked together for some years on staging a musical version of Tommy, and Pete had accepted his invitation to perform. It made the perfect finale to an astonishing evening.

More than anything, it made me proud of Canada—that an event like that could embrace the country’s artists across such a broad spectrum, from high-falutin’ artsy types to rock bums like us, and represent them with international luminaries like Matt Stone, Pete Townshend, and Salman Rushdie. It must have taken a great deal of time, energy, and money to put together all of those events, and I couldn’t imagine it happening in any other country.

Photo by Tom Sandler

We were ushered backstage to meet up with Matt and thank him warmly for doing us that honor, then into Pete Townshend’s dressing room. Usually I don’t care much about meeting celebrities, like the actors or athletes who come to Rush shows, but this was one meeting and photo op I was more than glad to attend.

To briefly recap a long history, The Who were my first favorite band. In my mid-teens, my bedroom was papered in magazine photographs and posters of The Who, hung with pop-art mobiles I made from photos of them, and my dresser had a Union Jack painted across its top (a triumph of clumsy masking and brushwork). In the middle of one wall I had painted the bass-drum logo from Keith Moon’s famous “Pictures of Lily” kit. (Another challenge for my mediocre artistry with paints.) I possessed every one of their singles, albums, and compilations, and every magazine that mentioned them. On the “drumset” I made across my bed from old magazines, in the layout of Keith’s drums, I could play along with all of their songs.

Around that time I had a high-school science teacher who was exasperated by my constant finger-tapping on my desk. When I said I couldn’t help it, he said, “What are you—some kind of retard?”

Seriously.

He sentenced me to a detention in which I would have to sit and tap on a desk for one hour. I played Tommy from memory; the teacher had to leave the room.

To the teenage me, Pete Townshend set the example for what a rock musician should be: “He smashes guitars—and reads books!”

So . . . meeting him now, forty-odd years later, I remained full of admiration, respect, and gratitude—for his example.

As we shook hands, I was pleased to tell him that my first concert, at age fifteen, had been The Who, with the Troggs and the MC5 opening. He smiled at the notion of losing my concert virginity to that mix!

The conversation among the four of us was a little halting, necessarily, but when we told Pete we had just finished making an album, he scoffed, “Waste of time, making albums these days.” We said we knew, but had to do it anyway.

Pete told us about some volunteer work he had been doing in a British prison, trying to encourage the inmates to explore music. He said, “All they want is decks”—meaning to be DJs, not musicians.

As we turned to leave, I made one last comment to Pete. “I also really enjoyed your prose writing—are you doing any more of that?”

He told me he was just finishing writing his life—which I took to mean in quotation marks, as “life,” like Keith Richards’ autobiography.

He went on, in his soft, sonorous voice, the accent melodic and pitched perfectly between Cockney and Oxbridge, “A lot of people thought Horse’s Neck was about me, but it wasn’t, really.”

I nodded agreement with that observation. I had learned from my own attempts at fiction that if you invent a story about an entirely imaginary musician, say, naturally people smell thinly-disguised autobiography. That is partly why my own prose writing shifted to non-fiction. If you follow the dictum, “Write what you know,” it is difficult, and unnatural, to stay away from the characters and settings of your own life.

If those characters and settings happened to be drawn from other youthful experiences, like sailing—Melville, Conrad, London—or war—Hemingway, Mailer, O’Brien—then you had the makings of fine fiction.

Backstage, not so much.

In any case, for me non-fiction was and is liberating—I can write about being a musician, a birdwatcher, a motorcyclist, a reader, a cross-country skier, a cook, or an opinionated faith-basher. The broadest possible canvas in which to fail.

A quote from Hans Christian Anderson gave me my title, “Where words fail, music speaks.”

Here Matt Scannell and I are speaking that language. On April 16, at Henson Studios in Hollywood (across the hall from where Rush had just been working on the final mixes of Clockwork Angels), we recorded a drum track for a Vertical Horizon song called “Instamatic.” Our method was pioneered by Nick “Booujzhe” Raskulinecz and me earlier this year, for that Rush album. (See “At the Gate of the Year.”)

The basic theme of that method is minimal preparation—just listen to the song a couple of times to get a “sense” of it, then start recording. My conductor, Nick or Matt, guides me through the arrangement with a drumstick, counting me into the various changes, and giving me suggestions and encouragement between takes.

I have described before what a huge breakthrough this is for me in my approach to recording, and—I think—in the character of my playing. Where I have always painstakingly worked up carefully-orchestrated and detailed drum parts and then delivered them from memory, now I improvise my way through from the get-go. A month or so before the Henson session, Matt and I had worked on a demo for the song, and explored a few ideas that seemed to work. But even then, I had even been careful not to listen to that demo more than a few times—because I wanted the final recording to capture a performance as fresh, and uncertain, as possible. Wild flights can happen in the heat of recording, in the course of shaping a part that is faithful to the song, but remains necessarily edgy, fresh, a little dangerous, and hopefully exciting for the listener.

It was certainly exciting (and fun) for the drummer and producer! At the end of each take Matt and I would share smiles, laughter, and excited chatter. (My wife, Carrie, says that when the two of us get together, we are “like a couple of puppies.” That’s kind of nice.)

While I was playing, Matt’s dancing was . . . enthusiastic.

Coincidentally, thinking about Pete Townshend and The Who, and the enduring influence of Keith Moon’s drumming on my own, it occurs to me now that certain parts of my performance on “Instamatic” suggest what Keith Moon might have sounded like if he too had lived to be almost sixty—instead of dying from an overdose of anti-alcoholism medication at age thirty-two. Too soon, and too sad.

I have much to be grateful for in my working life, but perhaps paramount to me is the opportunity to collaborate at a level of mutual delight with a circle of friends—musicians, artists, writers, producers, designers, editors (brother Danny this time), drum makers, cymbal makers, and . . . all the way around.

“Six Degrees of Bubba,” as a friend once described it.

Outside of music’s language, there is the language of friendship, and Matt is one of my dearest friends and collaborators. We have combined music and lyrics for a rock ballad, “Even Now,” and I played drums on that and two other songs on Vertical Horizon’s Burning The Days album. We also composed what we thought was a very fine country-pop song (just to prove it was possible!) called “A Promise or a Threat.” It will be a huge hit one day, when the right male “hat” singer discovers it. We have also written a fun theme for a cartoon show, which remains unproduced—but never mind, we had fun making it.

And, famously, there are our grand conceptions for the Broadway stage, like “Snowdance” (See “The Best February Ever”) and “Supernatural Lover” (“A Winter’s Tale of Summers Past”).

In our classic ironic, arch tone, Matt and I modestly assert that, “When we are together, magic happens.”

Certainly it is true that when we get together, music speaks.

Another example of music’s incomparable “speaking voice” was seeing the Jack DeJohnette Trio perform at Catalina’s jazz club in Hollywood in mid-May. The other—oh, let’s say “iconic” just this once—members of Jack’s trio were Chick Corea and Stanley Clarke. Together they created sublime, wordless music, with the classic palette of grand piano, upright bass, and sweet-sounding drumkit.

Jack’s playing was supremely delicate and subtle, yet interspersed with deceptively complex rhythms and cymbal shadings, and a constant, yet seemingly-effortless pulse. Driving home after with my friend Chris Stankee (also Jack’s representative from the Sabian cymbal company), we talked about the rhythmic lilt that lingered, echoing in our minds’ ears. It was a Latin kind of syncopation, but the astonishing thing was that it was a rhythmic statement they had never actually played, but only implied in the inner clockwork of their music.

(A note about the photo of Jack and me: in the background is a poster of “A Great Day in L.A.: A Celebration of Jazz,” which features my late teacher Freddie Gruber in the front row. Freddie was very proud to have been part of that, as it replicates a famous photo from 1958 called “A Great Day in Harlem,” which Freddie always had in his house. Also, this was the same “green room” in which the photo of Freddie, Roy Haynes, Jim Keltner, Ian Wallace, Ndugu Chancler, and myself was taken—see “At the Gate of the Year.”)

Jack DeJohnette’s career has been wide-ranging, and always at the highest elevations of modern jazz—from Miles Davis to a stellar recording called Parallel Realities with Pat Metheny and Herbie Hancock, to an entrancing duet called Music from the Hearts of the Masters, with Foday Musa Suso, a West African playing the kora (a stringed instrument resembling guitar and harp). I believe Jack DeJohnette bridges the traditional and modern styles of drumming more than any living player. His boundless virtuosity and improvisational eloquence are truly inspiring.

There’s a quote by Bob Dylan I have repeated from time to time in interviews for years.

The highest purpose of art is to inspire. What else can you do? What else can you do for anyone but inspire them?

Where words fail, music speaks.

Sometimes pictures fail, too—and need words to clarify them.

If “Art is the telling of stories,” then some stories require more than one art. Words and music, say, or words and pictures.

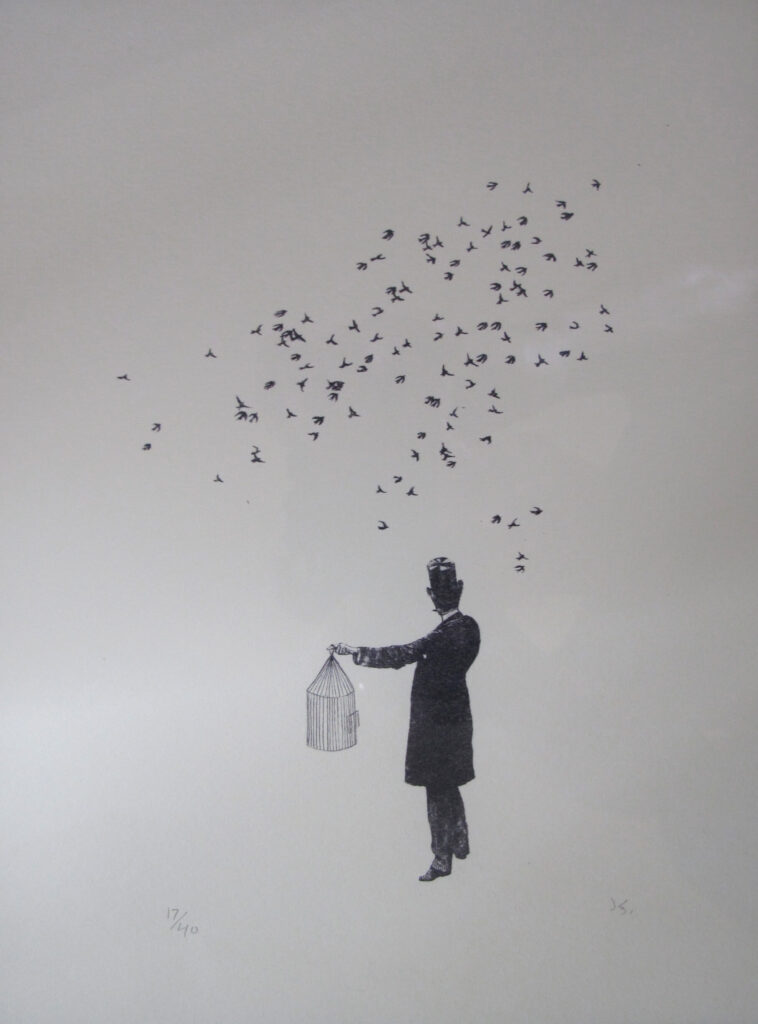

This print was given to me by my friend and fellow bird-lover Craiggie. He found it through a serendipitous thrift-shop connection, and knew I would like it. The image of a Victorian gentleman setting free a flock of birds from a wire cage would seem a happy and blameless image, and a pretty metaphor. But alas, Craiggie and I knew that the reality was far from happy, blameless, or pretty.

In the late nineteenth century, a British drug manufacturer named Eugene Schieffelin got it into his belfry that all of the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays should be introduced to the United States.

Let us just pause on that notion for a moment . . . while we consider the artist.

I admired the skill as well as the irony of the drawing, and wanted to know who the artist was. All I had to go on were the initials “J.S” penciled on the print (17 of 40), and I feared the work might represent one of the many unrecognized hobbyists whose art appears only at flea markets, yard sales, and thrift shops.

By a stroke of interluck, I searched Schieffelin’s name plus “drawing,” and stumbled on an oblique connection (as you do). A friend of the artist happened to quote something about her on her own site, and gave me the name—Julianna Swaney. I also learned that she had titled the drawing, “Oh My Cavalier.” (Nice twist on the adjectival form: “offhand and often disdainful dismissal of important matters.”) About it she said, “I always liked the strangeness of this story and the image of a fancy nineteenth-century man releasing cages of birds in a snowy landscape.”

Schieffelin’s plan to introduce all of the birds mentioned in Shakespeare’s plays began with skylarks and thrushes, but they did not thrive. Where skylarks failed, starlings succeeded—all too well. In 1890-91, “Our Cavalier” released one hundred British starlings in New York’s Central Park, and thus launched an avian plague. Despite the starling’s pretty name, and a plumage speckled with flashy iridescence, they breed prolifically, nest and feed opportunistically, and bully weaker birds out of their way. Within about fifty years, starlings had spread across the continent. The shadow of their inexorable path westward was the displacement of native woodpeckers, flycatchers, swallows, and bluebirds, and today scientists at Columbia University estimate the North American starling population at 200 million—all descended from Schlieffelin’s hundred birds.

Flocks of up to a million starlings, called “murmurations,” can be dazzling as they perform synchronized aerial ballets across the evening sky, like schooling fish with telepathic motion. But those same flocks can devour twenty tons of potatoes in a day, and choke jet engines to death—mechanical and human. In 1960, an airplane taking off from Boston flew into a flock estimated at 10,000 starlings—strangling the engines, and killing sixty-two people.

Attempts at eradication included broadcasting starling distress signals, placing artificial owls, spraying detergents and poison, firing roman candles, and stringing electric wires around the Capitol columns in Washington, D.C. In 1931 the U.S. Department of Agriculture even released a recipe for “starling pie”—presumably at least a little tempting during the Great Depression—but nothing availed. Like other invasive species such as kudzu, zebra mussels, killer bees, the Russian thistle (better known as tumbleweed, a symbol of the American West as potent as the saguaro cactus), and fire ants, starlings are here to stay—no matter how much I would prefer bluebirds.

Here is another deceptive image of birds in flight. The scene is Malibu Lagoon, nearing sunset on a Sunday afternoon in December, 2011. The beach was tranquil, only a few small groups of people here and there, silhouetted on an isthmus of sand between the surfer-dotted Pacific and the waterbird-dotted lagoon.

In the background is the Pacific Coast Highway, a justly famous Sunday cruising ground for cars and motorcycles, and just at this moment a battalion of open-piped V-twins shattered the evening peace. (You know the kind.) If those Sunday-afternoon outlaws took any notice at all, perhaps they laughed to see the frightened birds panic and circle into the sky.

Words fail, pictures fail, people fail.

What hope, then?

Well, great art never fails. And we can always try again—try to do better next time. There is always hope in the spirits of those who do try, in words, pictures, music, and everyday living.

“Lifetime achievement” is all about trying, really. The proper reward for any success is love and respect, and perhaps the only award for failure is the opportunity to try once more.

Even if it takes a desperate flight of 5,923 words and twelve photographs—only to fail again.

As Samuel Beckett said, “Try again. Fail again. Fail better.”

There will be another time, another place, another story.

And there is always music.